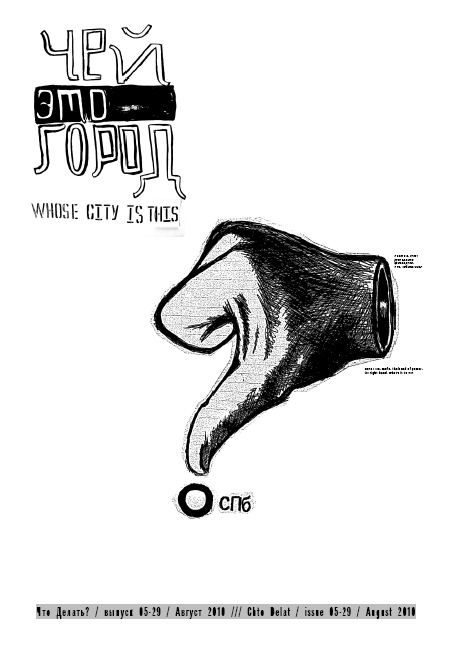

#5- 29: Whose city is this?

Editorial: Whose City Is This?

In this issue we return to a leitmotif of our platform’s work since Chto Delat was formed in 2003 – the right to the city, specifically, the city where many of us live and work. Back then, during Petersburg’s tricentennial year, some of the group’s founding members organized an action, “New Foundations of Petersburg,” in which they demonstratively abandoned the historic center for the outskirts. There they symbolically laid the cornerstone for a new city informed by avant-garde practices in architecture, art, and social organization. In the manifesto they wrote for this occasion, they argued that the city’s political and cultural elite had resorted to a suffocatingly conservative rebranding of Petersburg’s history. Long-dead neoclassicism and art nouveau were promoted to the exclusion of other – revolutionary and dissident – currents in that same history: the brief flowering of the first avant-garde and constructivist architecture during the twenties and early thirties, and the nonconformist arts and literature community of the late Soviet period, not to mention the three political revolutions of the early twentieth century. Skipping over potholes underfoot and scanning a skyline of leaky rooftops as they wandered this distorted cityscape in their imaginations, the authors of this manifesto also rued the fact that not a single structure worthy of the term contemporary architecture had been built in Russia’s so-called cultural capital since Petersburg reverted to its original name in 1991.

Dmitry Vorobyev & Thomas Campbell // The Gazprom Tower: Everything Changes for the Better! (1)

What follows is an attempt—in mid-story—to briefly capture some of the key moments in the attempt by the Gazprom corporation and Saint Petersburg city hall to build a 403-meter-high skyscraper near the downtown of the city, a Unesco World Heritage Site. At present, no one knows for certain why Russia’s economic and political powers that be have decided to erect a building that will certainly have a negative impact on the city’s historic (low-rise) appearance. Many tower opponents argue that the tower is a symbolic or vanity project for the ruling elite, which, like other newly wealthy “Asian despots” (in the Middle East and East Asia), wants to visualize its more or less unchallenged power in this way. In reality, the conflict is more interesting because this as-yet-nonexistent skyscraper has generated a highly divisive debate (verging on low-scale partisan warfare) on such questions as historical preservation, economic and architectural modernization, and the role of political institutions and “civil society” in deciding these issues. The tower controversy has revealed the class and ideological fault lines in Petersburg society: marginalized opposition parties pitted against the new nomenklatura represented by Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party; conservative local architects versus international architecture superstars; romantic but mostly powerless connoisseurs of the city’s almost-sacred “cultural legacy” (the “intelligentsia”) against fellow citizens who see the skyscraper as a short circuit into a future seemingly denied by the weight of so much “dead” (built) history.

The focus of this conflict is a small island in the mouth of the Okhta River, where it empties into the Neva River. At present, a visitor to the site will be greeted by a 10-meter-high fence bearing the inscription, “Okhta Center: The Impossible Is Possible.” Behind this fence, archaeologists sift through the buried ruins of two pre-Petrine Swedish fortresses, while a group of workers and engineers supervised by the Dubai-firm Arabtec Construction prepares the site for construction of the tower, which was originally scheduled to be completed in 2012 (now revised to 2016) as the first phase of the so-called Okhta Center development.

Alexander Skidan // String Quartet of Impotence

The film The Tower: A Songspiel is an acutely topical sociopolitical musical satire. It was conceived in this way and produced accordingly. The film is chockablock with witty, biting lines and episodes, and a great deal of humor and fun (at the premiere screening the audience laughed heartily in all the right places), but it makes for oppressive viewing on the whole. This is mostly due, of course, to the finale: entangled and crushed by tentacle-like red phone lines, the “grassroots” are frozen in unambiguous poses of resignation, defeat, and impotence. This final scene is accompanied by a surprisingly classical-sounding, agonizingly interminable chamber music coda, which is appropriately designated in the screenplay: “string quartet of impotence.”

The screenplay for the video film “The Tower: A Songspiel”

The Characters:

1. Gazprom PR Manager (PR Manager)

2. A Politician

3. The Head of Corporate Security (Security Chief)

4. A Church Representative (Orthodox Priest)

5. A Successful Gallery Owner (Gallery Owner)

6. A Hip Artist (Artist)

The Chorus:

1. Members of the Intelligentsia (Intelligentsia)

2. Pensioners

3. Workers

4. Fired Office Clerks (Clerks)

5. Migrant Construction Workers (Migrants)

6. A Leftist Radical (Radical)

7. Civil Rights Activists

8. Young Women

9. A Homeless Boy

10. A Giant

In the center of the stage we see a high podium on which the characters have gathered at a round table. A meeting is taking place to discuss a new image for the Gazprom tower project. There is a large black telephone in the middle of the table. A thick network of red telephone lines runs from the telephone down through the podium, spreading across the entire stage. The Chorus is situated below the podium. During the songs, it dances and moves around the podium. A camera on a dolly tracks its movements: the bad infinity of pointless gyration.

Galina Stolyarova /// Golden Potatoes and Dried Butterflies

www.tol.cz

August 16, 2010

Conservatism and lack of a coherent urban vision are having a strange effect on St. Petersburg. While faceless office blocks proliferate, cutting-edge architecture is scorned by officials and the public alike.

Galina Stolyarova is a writer for The St. Petersburg Times, an English-language newspaper

ST. PETERSBURG | Russia’s second city and former imperial capital attracts more tourists than anywhere else in the country. Visitors come from around the world to marvel at its architectural landscape. These views, however, have been undergoing dramatic changes over the past decade.

As the city administration tries to boost foreign investment and attract and accommodate new and expanding businesses, many charming historical buildings are being destroyed to make room for glass and concrete business centers. According to the St. Petersburg pressure group Living City, more than 80 such buildings have been destroyed in the heart of the city, and dozens more remodeled.

At the same time, stylish new architecture is having a hard time finding its way into this captivating city, where architectural experiments are regarded as a threat to the city’s priceless historical legacy.

As Alexander Viktorov, St. Petersburg’s former chief architect, put it, “New architecture is welcome to the city, but it is not for the architects to dictate their terms to the city; it is the city of St. Petersburg that dictates the rules of the game and sets its conditions.”

Selection of Related Articles on the Gazprom Tower

статья о Башне Зогнгшпиль в газете “Деловой Петербург”

https://www.dp.ru/a/2010/10/11/Pro_neboskreb_Ohta_Centr

Татьяна Лиханова. Ответит ли Вера Дементьева за дезинформацию? Председатель КГИОП обвинила ЮНЕСКО, общественность и СМИ в распространении дезинформации. Однако анализ ее собственных

высказываний заставляет переадресовать упреки госпоже Дементьевой.

https://www.zaks.ru/new/archive/view/72523

English-Language Media on the Gazprom Tower, July 2006 – January 2010 (compiled by Petersburg journalist Sergey Chernov)

https://docs.google.com/View?id=dfb4tc3w_1169nz2d5dt

Dmitry Vorobyev & Thomas Campbell. Anti-Viruses and Underground Monuments: Resisting Catastrophic Urbanism in Saint Petersburg

https://www.metamute.org/en/Anti-Viruses-And-Underground-Monuments

Chtodelat News. The End of Saint Petersburg, or The Beauties of “Kettling”

https://chtodelat.wordpress.com/2009/10/08/the-end-of-saint-petersburg-or-the-beauties-of-kettling/

Chtodelat News. Saint Petersburg versus Gazputinburg

https://chtodelat.wordpress.com/2009/10/16/saint-petersburg-versus-gazputinburg/

Chtodelat News. How Things Were Done In Petersburg: The Destruction of Submariners Garden

https://chtodelat.wordpress.com/2008/07/24/submariners/

Owen Hatherley. To the Finland Station

https://nastybrutalistandshort.blogspot.com/2010/05/to-finland-station.html

Owen Hatherley. In Which We Storm the Winter Palace

https://nastybrutalistandshort.blogspot.com/2010/05/in-which-we-storm-winter-palace.html

Dmitry Vilensky /// Afterword to the publication of the Whose City Is This? issue of Chto Delat newspaper

The question we posed in this issue was not merely the demonstration of a researcher’s idle interest in questions of developing the urban environment; it unexpectedly turned out to be a thorny question of everyday life and work in our city. The theme of the number was a litmus test to inspect control over the state of the city’s printing houses. When tested, these “independent” private businesses were revealed to be obviously dependent, as it is accepted in our country, not on legal norms, but on entirely explainable fears that the local authorities can always find a way of interfering in their business if some publication or other appears to them inappropriate.

Four Petersburg printing houses refused to print this issue even though, after reading the texts, they all expressed total agreement with the publication’s position. They did add that, in their situation, they were unable to publish something that criticized the city’s policies and Gazprom in such a fashion, since the risk of running into serious problems was too high.

The answer to the question we ask in the title of that issue of our newspaper seems banal and obvious: to whom does it belong? We know to whom: to those who control the city; to those who are in power; to those who have money; to those who are able to profit from real estate speculation, from controlling production, from receiving dividends on paid education and medicine. And you don’t have to be a Marxist to understand this elementary truth: a city, like a factory, belongs to the people who control the profits and means of production. And just as factories do not belong to their workers, neither do cities (not only Petersburg) belong to the people who live in them.