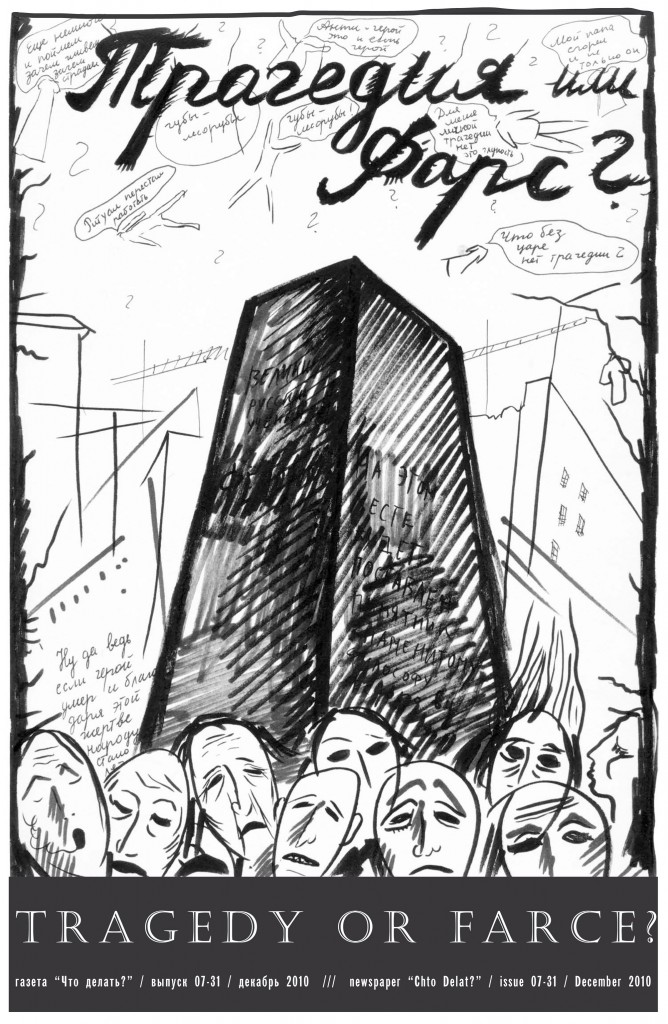

#7- 31: Tragedy or farce?

David Riff // Reluctant Notes on Tragedy

Ignorance is a demon, we fear that it will yet be the cause of many a tragedy.

Karl Marx

1. Not that I have anything against grand narratives. But the word tragedy makes me cringe, and not because this time is suddenly is out of joint with its mere mention, but because the context it opens is so imposing and at the same time so limited, like all great classical forms. The boundaries of tragedy – be it Attic or Elizabethan, Swedish or American – are historically determinate. And not just in the sense that they depend on a certain mode of production or its instability, but also in the formal sense. That is, the tragedy – especially in its ancient Greek version, as seen today – depends on closure. It is an ancient machine that still miraculously works, if its limitations are respected. Its “rhythm of sacrifice” (Raymond Williams) has to be timed perfectly, then it can survive even the most radical decontextualization.

This remarkable closure of form is connected to the subject matter of tragedy itself: the central conflict between conscience and law, two perfectly legitimate ethical prerogatives. The tragic break marks the point at which both prerogatives fail. This failure can only be rectified through an act of individual sacrifice that provokes both pity and terror on the part of the audience. The sacrifice reestablishes both limitations. But the definition of humanity thus produced – the heroism of the sacrificed figure – will ultimately make the entire system go under. The tragedy, in short, is a drama of how contradictory limitations are reproduced in an all-too-human history that ultimately negates them. (1) I am taken aback at my own megalomania for even agreeing to write a text on such a closed subject. Is it possible to reclaim a form so bounded? Better perhaps at this point to remain silent. But even that is suspect. What chance does Antigone stand in the age of online HD “Battlestar Galactica”?

Alexander Skidan // Catastrophe

And we sang the Warszawianka.

With reed-choked lips, Petrarca.

In tundra-ears, Petrarca.Paul Celan (1)

We can single out four key elements in Greek tragedy, elements that today have either been irretrievably lost or, at least, have become problematic. First, the connection between tragedy and the ancient mysteries: tragedy has its origins in rituals dedicated to the god Dionysus. The cult of Dionysus or Bacchus involved a (temporary) ecstatic escape from the established cultural order, the revocation of fundamental boundaries and distinctions – social, gender, sexual, and even anthropological (between god and man, between man and beast). The Bacchic frenzy concluded with the dismemberment of the god’s body or that of his deputized victim (the goat or tragos), thus indicating the ritual – sacrificial – source of tragedy. Second, this transgressive drama was matched by the utterly exclusive – sovereign – status of the characters: they were heroes in the strict, ancient Greek sense of the word – warrior chieftains, demigods, prophets, kings, their blood relatives and their retainers. In the baroque period and, later, in classicist tragedy and romantic drama, they were joined by generals, tyrants, tyrannicides, and outstanding individuals, people who rose above “the crowd” – that is (again), by figures who embodied supreme power, hierarchy, and the law, and who simultaneously transgressed this law. The third obligatory element is the fatal course of events, destiny. Its structure is paradoxical. On the one hand, irreversible consequences are provoked by unrestraint and audacious behavior on the part of the hero, the hubris that calls down catastrophe not only on him but also on the community (the kingdom, the country). On the other hand, fate is something predestined, something proclaimed from on high. The hero strives with all his might to avoid this destiny, but it is precisely his efforts that lead to excess and release the mechanism of catastrophe. Finally, the fourth element: the hero’s tragic insight, his horror at realizing how irreparably far he has gone. The catharsis (2) experienced by the spectator corresponds to the hero’s insight.

Keti Chukhrov // The Topology of the Tragic

1. Performance as Tone

In The Origin of German Tragic Drama, Walter Benjamin attempts to delimit tragedy and baroque drama. According to Benjamin, the basic characteristics that pluck baroque – that is, modern – drama from the logic of the tragic are as follows: transformation of the tragic hero into a martyr or saint; rejection of the silent solipsism of the tragic character in favor of the rhetoricized consciousness of the melancholic hero; the emergence of elements of dialogue, enabling the accommodation of the tragic and the comic; and, finally, the predominance of allegory over symbol – that is, the images of the tragic give way to the sacral function of allegorical signs.

Despite all these important differences between ancient tragedy and melancholic baroque drama, what unites these two genres is no less important, in our view, than what divides them. In other words, there is a certain poetics of the work of mourning both in ancient tragedy and in baroque drama that is independent of a particular age.

It is curious that Benjamin addresses the significance of sound and voice for baroque drama only at the very end of his work. And he does this in order to designate the crisis of baroque allegorical hieroglyphics – baroque drama’s principle quality – a crisis provoked by the introduction of the acoustic component into drama. Although he recognizes that the entire baroque system of allegories is mute and lifeless without the voice, Benjamin nevertheless argues that the reconciliation of sound and sense – as, for example, in seventeenth-century opera – marks the collapse of the Trauerspiel. Sound and voice imply a delay in the deployment of meaning and dramatic intrigue, and this leads to the evisceration of dramatic construction and allegorical significance. He writes: “For the baroque sound is and remains something purely sensuous; meaning has its home in written language. And the spoken word is only afflicted by meaning, so to speak, as if by an inescapable disease[.]”[1]

The Zero Point Where the Poles Converge, or, The Comic Reality of the Tragic // A conversation between Olga Egorova (Tsaplya), Artemy Magun, Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya (Gluklya), and Alexander Skidan

Olga Egorova (Tsaplya): Well, pour the drinks.

Alexander Skidan: Yes, let’s begin with the fact that alcohol – spiritus – is bound up with the spirit of the Dionysian mysteries that gave birth to tragedy.

Artemy Magun: As well as with sex and rock ‘n’ roll.

OE: Artiom, we all read your article and now we have a better grip on what tragedy is. But questions remain. In particular, what is tragedy in today’s world? Is there a place for it? Should we – artists, practitioners – create tragedies today?

АM: Well, what are your own thoughts?

ОE: You see, what we do is situated in some other dimension, although certain viewers of ours call it tragedy. But it doesn’t resemble tragedy.

АM: Because it lacks the element of exaltation, of catharsis.

ОЕ: Well, yes. Our work is kind of Brechtian playing at tragedy. For example, in The Tower, when the characters are frozen in the embrace of the red monster and corresponding music is playing, I’ve noticed that certain viewers have tears in their eyes. Does this have anything to do with tragedy?

Artemy Magun // Tragedy as the Self-Critique of Spectacle

In his theoretical notes on the theater, Bertolt Brecht often contrasts his own artistic method with classical tragedy. According to him, tragedy, as Aristotle described it, was based on “empathy.” Brecht argues that Aristotelian mimesis – that is, expressive imitation – is analogous to “empathy” or Einfьhlung, a concept from the neo-Kantian aesthetics of the nineteenth century. He thus writes, “Empathy is the cornerstone of contemporary aesthetics. Already in Aristotle’s magnificent aesthetics, it is described how catharsis – that is, the emotional purification of the spectator – is achieved with the aid of mimesis.” Brecht then goes on to ascribe to classical tragedy “hypnotism,” the task of “inciting emotions” and transmitting them from actor to spectator, as well as a timeless, “perennial” character. In contrast to this tradition, Brecht proposes rejecting empathy and creating a critically oriented “epic” theater in which the actor would distance himself from his character and “when, as he [showed] what he [was] doing, [would] in all the important places force the spectator to notice, understand, and feel what he [was] not doing.” Brecht calls this poetics, which he opposes to “empathy,” “alienation” or “defamiliarization” (Verfremdung), a word he borrowed from Shklovsky. He describes it just as Shklovsky describes it: art must emphasize its own conventionality and accidental nature, the surprise engendered by what it depicts, and, in particular, the historicity of the events it portrays. However, Brecht adds a moral-didactic element to Skhlovsky’s poetics that is missing in the original: alienation helps the individual realize the limitedness of depicted reality and look for alternative modes of action. It therefore leads to paradoxical, contrasting affects.

These principles of Brecht’s are manifested in his numerous works. The irony in characters’ monologues, the author’s own commentary, and the introduction of intermedia in the form of songs destroys the aesthetic illusion and heightens the conventionality of the drama. The tragic (sorrowful) aspect is interwoven with the comic (humorous), and the characters are presented as agents of ethical choice (albeit the wrong one). This critical, rationalistic aesthetic is quite winning, because it is meant to critique art in its traditional aesthetic conception and because it pursues avant-garde goals – that is, the overcoming of art and its transfiguration into life.