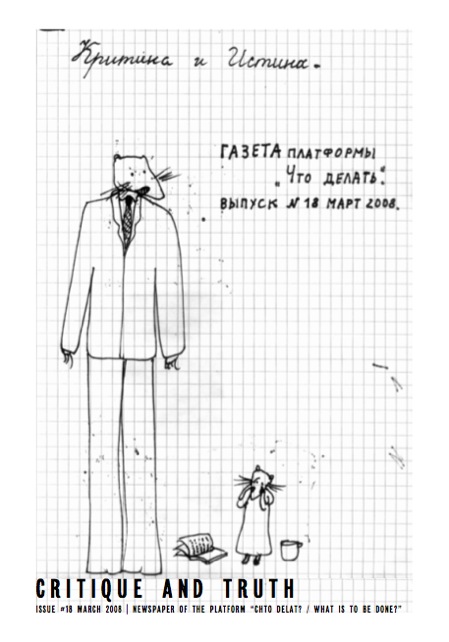

#18: Critique and Truth

Oxana Timofeeva /// Truth as Critique

There is theory and there is reality. Theory is made up of thoughts and words, while reality is made of places and things. Some claim that theory is a part of reality; others, on the contrary, feel that reality is little more than a theoretical construct. But no matter what we think, one thing is clear: between theory and reality, there is a huge contradiction. This contradiction reveals itself in the alarm we feel for good reason (or for no reason at all), wanting to invent a theory that would put all things in their proper place.

But things will trick you; they don’t listen to words, and that makes us suspicious. On the brink of the gulf between words and things, thought lingers like a specter that knows no rest. Suspecting words of falsehood or things of subterfuge, the course of thought sometimes takes on the respectable form of criticism, whose very idea arises from the obvious contradiction between theory and reality.

Igor Chubarov /// Instructions for Resistance: Between Army and Prison

By comparison with the situation in the west, the theme of institutional critique in contemporary Russia is complicated by several essential factors. The problem is that we are always a bit behind Europe-by a hundred years or so on average. This gap, however, is not quantitative in nature, but qualitative. It is therefore difficult for us, say, to assess the merits of Foucault’s provocative idea that the system of social disciplinary control that replaced public executions, corporal punishment, and the sovereign form of power in Europe during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries placed even greater restrictions on the liberty of the individual. For analogous changes have still not been made in Russia, and maybe they will never be. We must keep in mind that the institution of the prison itself was established in Russia only in the mid-twentieth century. In the Russian prison, however, the form of punishment that still predominates is not the restriction of liberty, but violence that is controlled only by the unwritten rules of prison life.

Dusan Grlja and Jelena Vesic (Prelom kolektiv) /// The Neo-liberal Institution of Culture and the Critique of Culturalization

The activities of Prelom kolektiv involve the making and editing of Prelom journal, organizing exhibitions, conferences and discussions, and participating in other artistic and cultural projects and events [1]. In a terminology often used today, this makes us “cultural workers” or even so-called “content providers” for the expanding “cultural industries” within the neo-liberal capitalist system. Although we oppose this kind of positioning and the whole constellation that produces it, this is precisely the starting point for an objective, i.e. materialist understanding of what the institution of culture is today.

Alexander Bikbov and Dmitry Vilensky /// On Practice and Critique

AB: It seems to me that we are coming from similar positions. We both use a critical vantage as our professional instrument to make new forms of knowledge. But it is impossible to use a critique as a professional resource on an individual basis, at least not for any extended period of time. Criticism only works when it belongs to a collective. This becomes clear when you look at the group Chto delat, which unites artists, poets, and philosophers, all of whom think critically, but did not have any position in common before the group came together. The same thing happened with a seminar we recently organized for intellectually curious sociology students at the Moscow State University. It started a laboratory to help students grasp critical theories of society, but, as time went by, it demanded a more and more complicated and consolidated organization. So, several years ago, I turned this seminar into a research group called NORI (the Russian abbreviation for Unofficial Association of Working Researchers). Its participants don’t just discuss texts but carry out research, using a common critical method. Bringing our work into a more practical and collective regime took away our fear of action, so that NORI joined the struggle against intellectual corruption at the sociological faculty of Moscow State University as part of the student protest initiative OD group (1). In reality, our new willingness to put up a fight is hardly surprising: intellectual ambition + the presence of a more experienced mediator and organizer + regular meetings and exchanges + the forming of a common critical competency a collective organization of the method of working. These principles have proven very useful to our work. In how far are they different from what you are dealing with in your practices with Chto delat?

Keti Chukhrov /// The Critique of “General Intellect”

I. (T)he crucial moment for the folk tale is not that of the parole, that of its invention or creation (as in middle class art). But that of the langue; and we may say that no matter how individualistic may be its origin, it is always anonymous or collective in essence. – Fredric Jameson

The revolution is (…) is the moment in which criticism, hitherto unarmed, recognizes its arms in the proletariat. It gives the proletariat the theory of what it is; in return, the proletariat gives it its armed force, a single unique force in which no one is allied except to himself. So the revolutionary alliance of the proletariat and of philosophy is once again sealed in the essence of man. – Louis Althusser

The philosophy of post-operaism undertakes a fundamental revision of Marx: it displaces the notions of work and production, claiming that these are no longer capable of offering adequate descriptions of contemporary capitalism under post-industrial, post-disciplinary conditions. According to Paolo Virno, the principal feature of neo-capitalism is the immaterialization of labor; it displaces commodities with the emergence of a “general intellect,” which, in turn, must resist governance through economic and juridical machines, undertaking an “exodus” from the apparatuses of state and capital.

In his book “The Revolution of Capitalism” (in the chapter “Enterprises and Neomonadology”), Maurizzio Lazzarato speaks of a stage of capitalism in which exploitation no longer takes place through work and production, but in the virtual zone of collective world-making, in the space of intellectual co-laboration or co-operation, which is then appropriated by a company or corporation.

Kirill Medvedev /// The “Liberal Intelligentsia”: A Brief Ideological Analysis

The “liberal intelligentsia” is one of the most popular and speculative notions in today’s political lexicon. For a start, we will try and understand who has the right to this honorary title.

If your occupation involves intellectual labor and you believe that ideology comes in two stripes-communist and fascist, and that normal (not crazy) people are definitely free of any sort of ideology and hold sensible, liberal market views; if you think that progress is a western movement whose avant-garde is staffed by the developed countries of the west, and is something that cannot be expanded, halted or changed, then you’re probably a member of the liberal intelligentsia in its contemporary Russian configuration. Of course, you will find liberals with much more complicated views. Here, on the contrary, we are focused on a kind of semi-conscious or unconscious ideological residue that has been absorbed as the property of a milieu, as the ideological mainstream of its day and age.

In the late Soviet period, the upper crust of this stratum had access to cultural goods that were forbidden, concealed or simply not advertised by the Soviet state. First and foremost among these goods was the culture of Russian modernism as well as the so-called blank spots of history-that is, the “skeletons in the closet” of the Soviet period. Accordingly, during perestroika this stratum acquired a kind of public educational function by communicating and interpreting these revelations and goods. In the early nineties, however, the main current of cultural and historical revelations ran dry, and the broader public’s interest withered. This stratum’s “mission” withered, too, and its natural cultural hegemony ended with it.

Artiom Magun /// Intellectuals and the critique

The uncompromising criticism against intellectuals (against their groundlessness, class egoism, idealism, passivity) is the favorite sport of intellectuals themselves, since they emerged as a stratum of society. There is something, in the intellectual’s position, that makes him/her dissatisfied with his/her position, which pushes him to go “into the masses”, into the public activism (first version), or into the practicism and simplicity of the “real life” (second version). Moreover, one may say that intellectuals, as such, are a contradictory class. The internal tension of its position consists in the fact that, having the best access to the total grasp of the society (science), and the leisure to imagine and think through the future possibilities (art), for the “experiments in being” (Nietzsche), it does not have political or economic power, neither as a whole (qua a solidary group), nor individually – examples of intellectuals coming to power are rare and are characteristic for the critical, destructive, or revolutionary moments. Moreover, while the intellectuals are close to the dominant class of society (bourgeoisie, in the Modern case), in their function and in their way of life, they do not coincide with it, but, on the contrary, often acts as a “fifth column” of other classes (aristocracy or proletariat), in its midst. All Modern revolutions were led by intellectuals, and intellectuals took part in them, en masse, both physically and ideologically. However, they usually lost their positions after the revolution’s victory because it turned out that, in their way of life they had been closer to the former than to the new dominant class, while the universal utopia of the destruction of classes and of the universalization of the way of life of intellectuals could not be realized.

David Riff /// Criticality or truth?

1. A specter haunts the world of cultural production, the specter of criticality. All too often, this specter is truthless, little more than a caricature of a ruthless critique. Its appearance invokes an “aesthetic of administration,” born of too many compromises between market, state, and freelance rebellion. This kind of criticality pretends to found upon Foucauldian parrhesia or Brechtian “plumpes Denken,” but it does not articulate the interests of “class conscious culture workers.” Instead, it is the global petit bourgeoisie’s version of what was called paidea in late antiquity, the polite and deferent gestural-discursive code of conduct for educated (i.e. recognized) subjects at court.

This weak criticality is what distinguishes the “reasonable” petit bourgeois from a run-of-the-mill consumer of decorative-spectacular kitsch; criticality is a hallmark of enlightened citizenship. But of course, today, criticality is also an industrial product, a bit like bio-food. Its function is supply a semi-privatized “public sector” a new aura of governmentality, to the irrational, maddening glory of an “intelligent” or “soft” power that pretends to yield and change to your benefit when you tell it the “naked truth.” This, of course, is a lie.