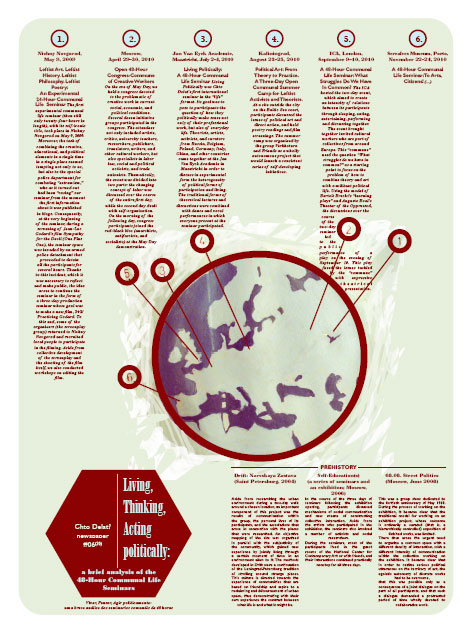

#06- 30: Living, Thinking, Acting politically

Oxana Timofeeva // Living Politically

The idea of organizing a communal seminar in Maastricht came to me in January 2010, when I arrived in the city from Moscow for two years to do research (on animals in philosophy) in the theory department at the Jan Van Eyck Academie. The Chto Delat collective and the Vpered Socialist Movement had already organized a 24-hour seminar in Nizhny Novgorod and were planning a 48-hour May Day forum for creative workers in Moscow. The goal of the Maastricht seminar was to integrate this form – “communal life seminars” – into the international context. Everyone saw this as an important challenge. When two active participants in the Nizhny Novgorod event, Nikolay Oleynikov and Kirill Medvedev, and I were in the early stages of the discussing the project, we asked ourselves a question. What if things that were apparent to us turned out to be completely unapparent to a European audience adapted to different political realities – for example, the meaning of the Soviet-era term obshchezhitie (both “communal living” and “dormitory,” “hostel”), which can hardly be adequately translated into English? But this was precisely the point of the project – to gather people from different contexts and force them to search for a common language of the “political.” A search like this is seemingly in the order of things, but what was really interesting and new was the fact that the premises of our experience, which in our local situation we considered self-evident or axiomatic, here became a barrier to understanding, and this barrier had to be overcome. The way we originally asked the question was: how do we – you and me – make sense not only of our daily lives, but also of professional work in political terms? To put it simply, what meaning do we invest in what we do and how we live? All this established yet another important dynamic of difference, which during the course of the seminar revealed itself, albeit fairly hypothetically, as a productive conflict between art, theory, and activism. Each of these forms of work has its own trajectory of desire, but the question is how, when, and where an intersection of these trajectories is possible, and whether it is possible at all. The title of the event – Living Politically – reflected both this dynamic, which informed the seminar’s content, and a formal moment: this was an event in the experimental format of “life,” that is, it was a matter of combining “life” and “politics” in a limited time and space.

The 48-hour communal seminar in Maastricht took place on July 2–4, 2010. This dialogue is based on a discussion that arose at the end of the seminar. Dmitry Vilensky, Oxana Timofeeva, Pietro Bianchi, Katja Diefenbach, Aaron Schuster, Alexei Penzin, Andrei Berdnikov, and others took part in this discussion.

Nikolay Oleynikov & Dmitry Vilensky // Creative Time in Common

Prehistory

Drift: Narvskaya Zastava (Saint Petersburg, 2004)

Aside from researching the urban environment during a two-day walk around a chosen location, an important component of this project was the results of communication within the group, the personal lives of its participants, and the associations that arose in connection with the places that were researched. An objective mapping of the site was organized in parallel with the subjectivity of the community, which gained new experience by jointly living through a certain moment of time in an environment alien to it. The methods developed in Drift were a continuation of the Leningrad-Petersburg tradition of strolling around strange places. This culture is directed towards the experience of communities that are based on friendship and aspire to a reclaiming and détournement of urban space, thus demonstrating with their own experience the contrast between what life is and what it might be.

Self-Education(s) (a series of seminars and an exhibition; Moscow, 2006)

In the course of the three days of seminars following the exhibition opening, participants discussed mechanisms of social communication and new means of constructing collective interaction. Aside from the artists who participated in the exhibition, the seminars also involved a number of activists and social researchers. During the seminars, most of the participants lived in the guest rooms of the National Center for Contemporary Art or with friends, and their interactions continued practically nonstop for all three days.

Maria Chehonadskih // 48 Hours of Common Effort: How Cultural Workers and Political Activists Met and Talked

The entire spectrum of problems connected with the condition of creative workers has recently become the focus of fundamental discussions and reflections on the part of the artistic community as well as a number of leftist political and social activists. These discussions have revealed points of convergence between creative workers and workers engaged in nonstandard forms of employment, which have become more and more widespread in Russia. The search for new ways of regrouping radical leftists, trade unions, and social movements makes new forms of dialogue possible. The 48-Hour May Congress-Commune of Creative Workers was the first initiative to task itself with tackling both theoretically and practically the host of problems connected with the nature of the work done by cultural workers and labor relations in the cultural field.

1. Informal Relations and “Protections of Proximity”

Precarity as the norm for labor relations in Russia emerged in the nineties in connection with the transition to the market economy. Shock therapy and a sharp decrease in production led to massive unemployment that was in no way regulated by the state. The first forms of self-enterprise played an important role in forming the new system of nonstandard employment: unemployed people united into groups and networks or operated independently, hiring others as “day” workers. As a system of labor relations, precarity emerged spontaneously and at the grassroots, via family ties and friendships, informal relations between former colleagues, and a broad network of mutual assistance and mutual dependence. Nonstandard employment was not officially recognized for a long time because this kind of (self-)enterprise was a semi-legal form of private business and part of the shadow economy. The situation remained invisible, and the problems occasioned by it were long left unarticulated.

Steve Edwards // Auto-critique of a Leaflet distributed by Stan Evans at the London Learning Play organised by Chto Delat (10th September 2010)

As representatives of Historical Materialism (a London-based journal of Marxist theory) Steve Edwards and Antigoni Memou participated in the 48-Hour Communal Life Seminar, convened by Chto Delat, ‘What Struggles Do We Have in Common?’ The seminar was productive in bringing together activists, artists and thinkers (and these need not be separate people) to talk and live together for two days. We met comrades from Russia and Belgrade; we also met activists, artists and media workers from Britain – even from our own city – who we did not know. Introductions of this type can be significant in developing networks of resistance to capitalism. We found the discussion fascinating (we talked much); the film screenings were instructive (we learned together); and we enjoyed the dumplings, vodka and the company (we laughed a great deal).

The question posed by the seminar is an important one for artists and activists, but so is the question ‘what struggles do we not have in common?’ One possible criticism of the seminar is that it lacked antagonism on questions of fundamental importance for all involved: is the distinction art and activism a genuine opposition? Is art activism in any way effective? What critical and theoretical resources do we need to create revolutionary change? Which legacy and which way forward? Who? Many questions; few answers.

In the learning play that emerged from the seminar Antigoni Memou played an activist; Steve Edwards (beside himself) intervened from the audience as Stan Evans who called for a boycott of the whole event as a mere charade of revolutionary politics served up for the well-heeled audience of the ICA. This intervention revolved around a leaflet written by Edwards and Vlidi Jerić of the Prelom Collective and issued under the name of the ‘League of Revolutionary Cultural Workers’.

Willem Jan Renders /// Malevich in Vitebsk

Almost a year after the Revolution, in September 1918, Marc Chagall was appointed Commissar of the Arts for the Province of Vitebsk by his old friend Anatoly Lunacharsky, head of The People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment (Narkompros). Chagall immediately started the cultural renewal of his native city, the provincial capital Vitebsk, presently in Northern Belarus. After organizing the elaborate decoration of the city for the occasion of the grand celebration of the first anniversary of the Revolution, Chagalls main goal became to create a professional art school and a museum there: the People’s Art School and the Vitebsk Museum of Contemporary Art. The school came first. The former residence of a local banker was provided for this purpose and Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, a former teacher of Chagall and a well known artist at the time, was appointed director. After some delays the People’s Art School opened on 28 January 1919. The event was postponed because of the commemorations in Vitebsk of the victims of the peaceful demonstration in Petersburg on 9 January 1905 and because of the recent murders of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa von Luxemburg in Germany on 15 January 1919. The official opening of the school was important to Chagall because he wanted it to be recognized by the revolutionary authorities as an official institution for higher learning. And the requirements on a national level for art education were high. At the opening of the State Free Workshops in de former Petrograd Academy in 1918 Lunacharsky had stated: “Despite our impoverishment, despite the impoverishment of Russia, we are on the way to a flowering of the arts, whether we want it or not. (…) A need has arisen to change the aspects of towns as quickly as possible, to express the new experiences in works of art, to get rid of a mass of sentiment obnoxious to people, to create new forms of public buildings and monuments. And this need is enourmous.” On top of these national ambitions came the fact that Chagall and so many of his Jewish fellow citizens were not allowed to study at the official art academies in Russia before the Revolution. This will have heightened the level of the ambitions for the People’s Art School. Chagalls ardent opening speech was paraphrased in the local paper ‘Vitebsk Izvestia’: