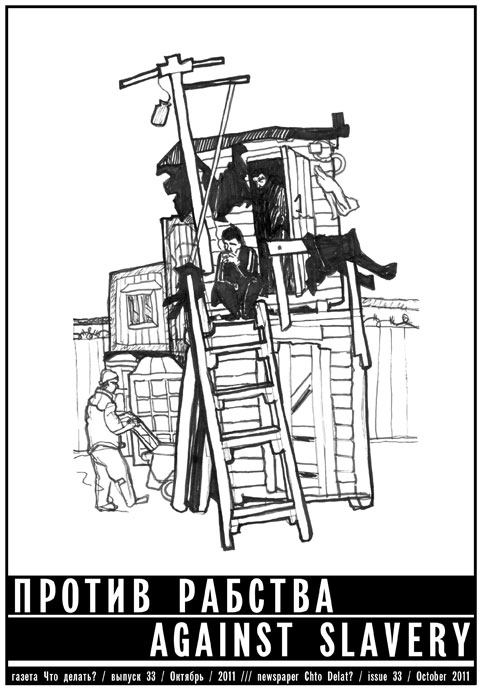

#09- 33 Against slavery

Dmitry Vilensky // Editorial

This issue of Chto Delat deals with migrant labor, an issue today at the center of not only Russian, but also world politics. Although our world has always been “globalized,” the numbers of people migrating in order to better their existence, whether economically or otherwise, are unprecedented. Discussion of this issue is complicated by the fact that we immediately find ourselves on slippery terrain occupied by the shadowy figure of the immigrant, who like the Wandering Jew in its time has come to function as a synonym for danger, contamination and the alien per se. Racists and nationalists of all stripes and lands rally round (so to speak) this fictional villain as they defend the supposedly homely but no less fictional spaces of nation, race and tribe from invasion by aliens. Judging by recent election results in certain “liberal democratic” European countries and legislative innovations in US states such as Arizona and Georgia, the “commonsensical” and “down-to-earth” slogans and prescriptions of the tribalists really are sometimes capable of generating a “groundswell” of “grassroots support.”

Some people have always found it hard to share their homelands, hometowns and neighborhoods with different languages, skin colors, and ways of understanding world, self and community. However, it is all too easy to accuse “the common folk” of being the source and support of xenophobic sentiments. As British sociologist Paul Gilroy has argued, when left to their own devices the “working classes” and “common folk” (whatever their “primary” tribal allegiances) are just as often capable of creating a “convivial” existence together, a life where each person’s allegedly essential difference informs and shapes a totally unexpected common good, a new commons. In reality, it is more often the liberal (or, now, neoliberal) talking and ruling classes, whose experience both with conviviality and the (non)realities of ethnic difference is frequently limited to a fondness for certain cuisines and holidaymaking in the global south, who shape the xenophobic and nationalist agenda via the media they produce and control, via the obscurantist norms and repressive laws they promulgate in the public space. It is this “common sense” from above that is the main instrument for stigmatizing and excluding people who sometimes lack the right language to tell us both about their plights and their joys, who frequently lack the right papers to exercise their individual civil rights and their collective right to struggle for a better lot in life.

Thomas Campbell /// What Are Deportees Doing in a Museum?

The answer they give in the film (via the intermediary of the guard) is: because they have heard that “art is on the side of the oppressed.” Although the details, as hinted at by the museum staff, are sketchy, we are led to imagine that the establishment of “national democracy” in Holland and other parts of (what can only be Northern and Western) Europe is so brutal that the escapees have nowhere else to turn but the museum. But what they find there is an identification with the oppressed, with the revolutionary and critical potentials of art, that is literally canned, contained, archived, monitored, and rationed. The museum has an extensive collection of “revolutionary” art, but the chorus acknowledges what this art’s fate has been in our world: as a paragon of “timelessness” (although revolutions are only timely, or they’re not revolutions), and as a source of that most counter-revolutionary of genres – reconstructions of historical avant-garde performances and installations. The characters deliver many of their lines against a backdrop of Black Panther newspapers – neatly framed and lined up on a wall and thus not likely to provoke any nice white person’s “fear of a black planet.” “Street art” is relegated to a panopticon-like space known as The Eye, which now serves as a jail cell-cum-theatrical stage for the ever-silent immigrants. Finally, contemporary art’s “critical” mission (“our job is to wake society up”) is so precious that any soft-pedaling of “criticality” is warranted to avoid closure or budget cuts.

Chto Delat’s Museum Songspiel: The Netherlands 20XX is a scary film, not least because it coldly and blithely illustrates how the current democracies (whether “social,” “liberal” or “sovereign”) disappear the undesirables in their midst, the refugees/asylum seekers, illegal immigrants, and “lawbreakers.” In this sense, the film – despite its flimsy gesture toward a dystopian future as its setting (“20XX,” “European National League,” “euthanasia” experiments carried out by scientists, etc.) – is not science fiction. It is firmly situated in the present: this happens nearly everywhere almost every day, however much we would rather not know about it. (And the scary part, as the film shows, is how conveniently we forget that we do know.) What makes it “science fiction,” however, is not these stock elements from a threadbare genre, but its resort to a wholly fantastical plot premise: the deportees seek to claim asylum, of all places, in a contemporary art museum. What are the deportees doing in a museum.

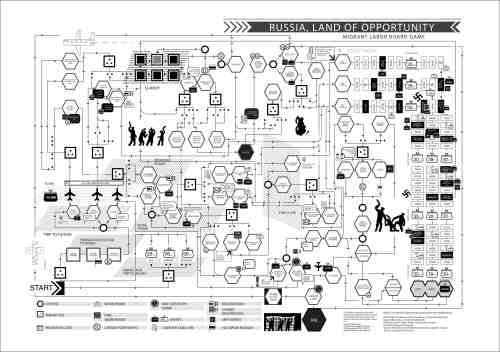

Board game “Russia – The Land of Opportunity”

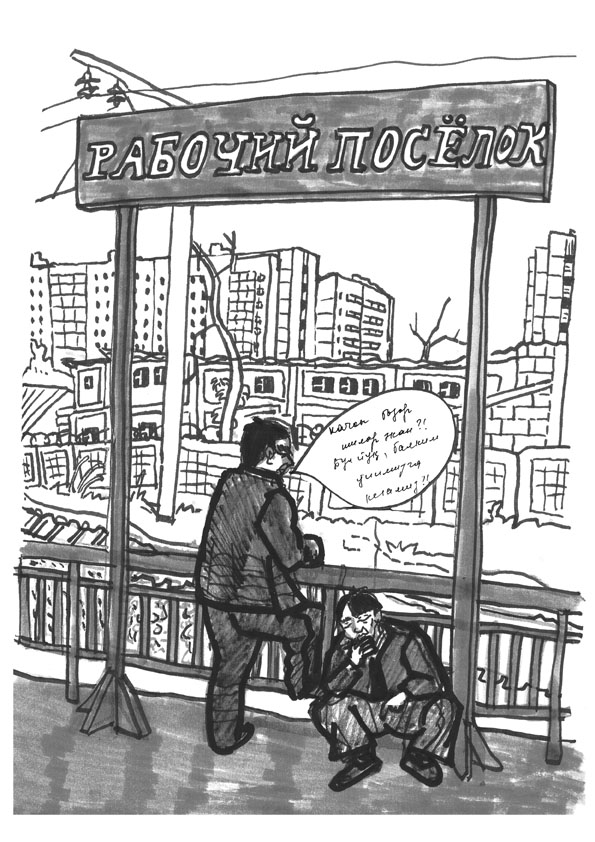

Russia, The Land of Opportunity board game is a means of talking about the possible ways that the destinies of the millions of immigrants who come annually to the Russian Federation from the former Soviet Central Asian republics to earn money play out.

Our goal is to give players the chance to live in the shoes of a foreign worker, to feel all the risks and opportunities, to understand the play between luck and personal responsibility, and thus answer the accusatory questions often addressed to immigrants – for example, “Why do they work illegally? Why do they agree to such conditions?”

On the other hand, only by describing the labyrinth of rules, deceptions, bureaucratic obstacles and traps that constitute labor migration in today’s Russia can we get an overall picture of how one can operate within this scheme and what in it needs to be changed. We would like most of all for this game to serve as a historical document.Olga Zhitlina

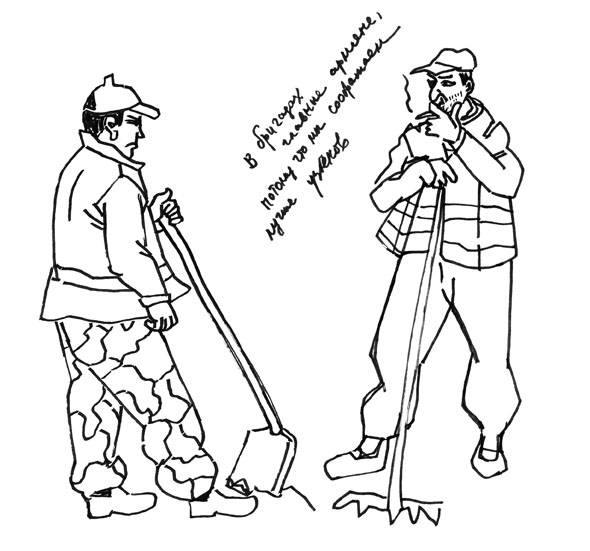

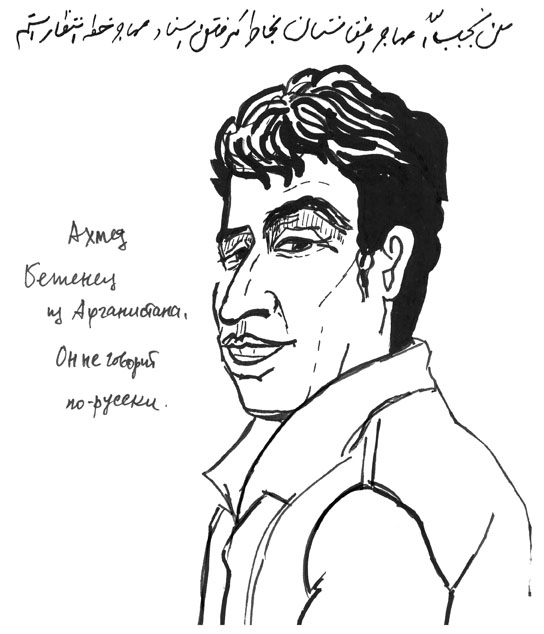

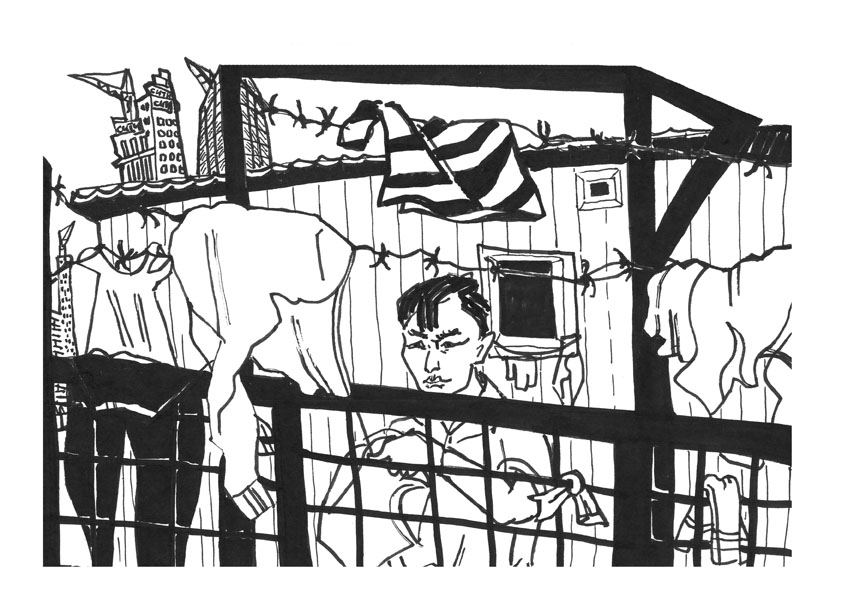

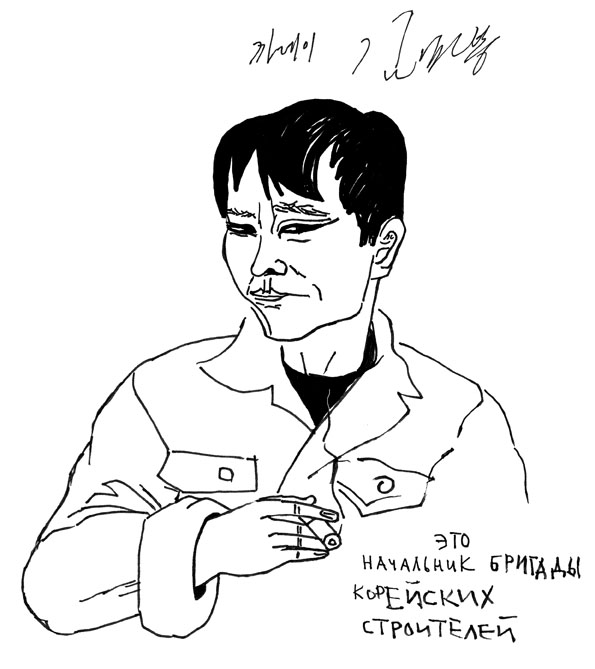

Russia, The Land of Opportunity: A Migrant Labor Board Game

The game is designed for adults and children of secondary school age.

From 2 to 6 players

The characters, situations, and monetary amounts (fines, payments, bribes, etc.) are not fictional. Any resemblance to actual events is not coincidental. Each year, thousands of people are victimized by the system outlined here.

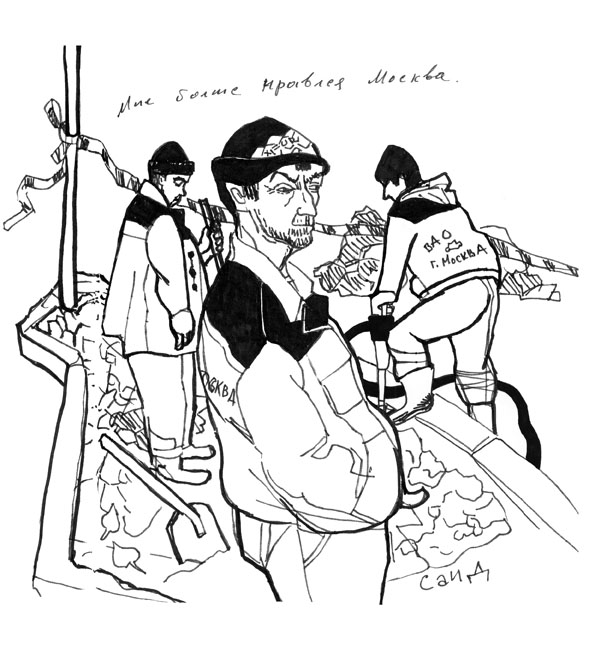

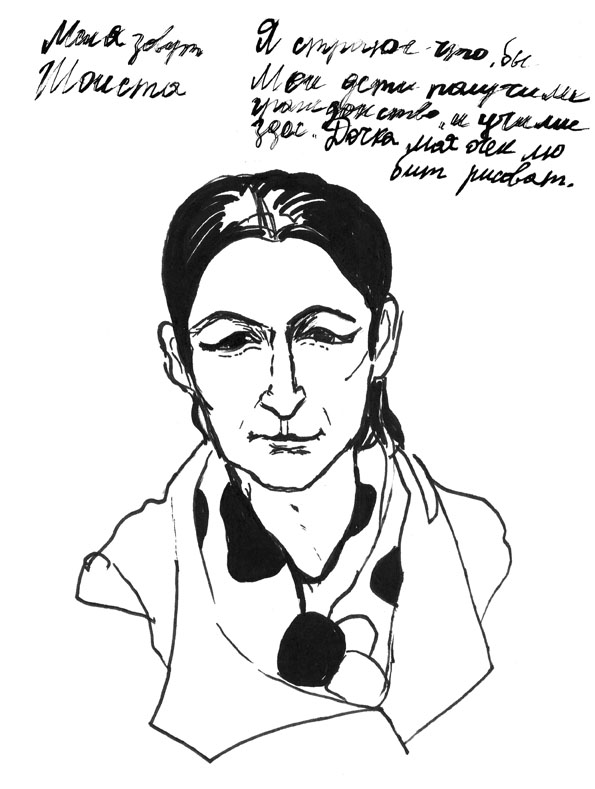

Illustrations by Victoria Lomasko

Read MoreThomas Campbell // The Persian Ambassador’s Cardiff Album

Born in Lerik, Azerbaijan, in 1959, Babi (Babakhan) Badalov is a living embodiment of cosmopolitanism’s dark and spontaneously convivial underbelly. In his world, people do not travel from one country to another with polished ease, flashing their passports to the guards as they pass effortlessly through frontiers and effecting the shift from one language to another with fluency and grace. On the contrary, when you are a refugee, exile, migrant worker or itinerant artist, you manage these transitions as best you can, mangling the new idioms you learn and fusing them with half-remembered tongues you picked up along the way, mingling them with memories of a mother tongue that never matured into adulthood because at a tender age you left your mountain village for the capitals, where encounters with countrymen were few and furtive and somewhat beside the point. In the provincial capital, you learned the official language of artificial nationhood along with the (un)official language of the anti-imperial empire, neither of them your own, both of them suspicious (of you and of themselves). This was violence to be sure, but you turned this violence back upon itself, never fully learning any of these codes well enough to pass for a native. Nativity, after all, is naпvetй, an identification both outwardly enforced and grimly self-willed. For an artist, whether of life or the brush, submitting to too many of these identity checks means submitting to kitsch and clichй.

Born in Lerik, Azerbaijan, in 1959, Babi (Babakhan) Badalov is a living embodiment of cosmopolitanism’s dark and spontaneously convivial underbelly. In his world, people do not travel from one country to another with polished ease, flashing their passports to the guards as they pass effortlessly through frontiers and effecting the shift from one language to another with fluency and grace. On the contrary, when you are a refugee, exile, migrant worker or itinerant artist, you manage these transitions as best you can, mangling the new idioms you learn and fusing them with half-remembered tongues you picked up along the way, mingling them with memories of a mother tongue that never matured into adulthood because at a tender age you left your mountain village for the capitals, where encounters with countrymen were few and furtive and somewhat beside the point. In the provincial capital, you learned the official language of artificial nationhood along with the (un)official language of the anti-imperial empire, neither of them your own, both of them suspicious (of you and of themselves). This was violence to be sure, but you turned this violence back upon itself, never fully learning any of these codes well enough to pass for a native. Nativity, after all, is naпvetй, an identification both outwardly enforced and grimly self-willed. For an artist, whether of life or the brush, submitting to too many of these identity checks means submitting to kitsch and clichй.

Hito Steyerl // Right in Our Face

First published at https://www.e-flux.com/journal/view/210

There is something deeply disappointing about the contemporary moment: it projects the past into the future.

I recently met some emigrants from Germany. I am not talking about йmigrйs who left in the 1930s to escape National Socialism. The people I met quietly decided they could no longer put up with Germany’s endless, debilitating, and deeply racist debates on immigration, and left the country in which they had been born and lived most their lives. These so-called debates had been going on least since the early 1980s, when anti-Turkish graffiti started appearing in the streets. Fueled by the so-called reunification in 1989, racist riots became the norm throughout the 1990s. I still vividly recall the accounts of a television crew in Rostock trapped in the elevator of a burning hostel for Vietnamese guest workers that had been attacked by a fascist mob for days on end—to the great amusement of the police forces standing by.

All of these quite practical acts of violence were greatly supported and even applauded by elites, who took every opportunity to express doubts about ethnic minorities’ genetic makeup, inherited lack of intelligence, inbred fanaticism, and perceived failure to assimilate. We cannot neglect the fact that contemporary racism is eminently class-driven: it has its stronghold not in the working class, but in middle classes panicked by global competition, as well as in elites, who use the opportunity to deflect from growing social inequality by dangling the prospect of race-based subsidies for the working classes. Jacques Ranciиre’s recent refutation of the phantasm of an assumed working-class passion for racism is an extremely important tool of analysis here. [1] Popular racist passion is seen as a primordially affective expression to be respected at any cost—and conveniently enables politicians to create racist policies to “acknowledge” them. But in effect, these passions are greatly exaggerated to allow room for middle and upper class racism to safely indulge itself, all the while remodeling the former First World as a defensive and resentful fortress. A bastille devastated from the inside by the delayed effects of shock capitalism, which have finally hit home. [2]

Kirill Medvedev // The Welfare State and Multiculturalism: An Ambivalent Legacy

Although all of today’s anti-neoliberal campaigns naturally appeal to the waning achievements of the welfare state, it is clear that neither this phenomenon in its previous form nor the specific ideological and psychological climate in which reflection on the Nazi catastrophe, Europe’s colonial past and the national liberation struggles in the Third World were entangled, will ever return. Certain qualities and contradictions of this system are thus manifested more clearly today, during its collapse, forcing us to reinterpret both the active solidarity demonstrated during the period of the Algerian War and the Vietnam War, and the passive tolerance that has come to the fore during the neoliberal period, a tolerance based rather on the European intelligentsia’s sense of guilt over colonialism and Nazism than on a solidaristic, equally empowered struggle for rights inspired by the universalist project of the sixties. The multiculturalist politics of the coexistence of different cultures and identities has been fully in keeping with this passivity.

As an ideology, multiculturalism was not specially devised by the bourgeoisie to divide workers, but emerged naturally within the anti-racist movements, in campaigns for civil rights that demanded the recognition of cultural differences, a recognition in whose absence the struggle for common, egalitarian goals is impossible. Cultural and other “stylistic” differences acquired inherent worth when common goals became more obscure and, later, dissipated altogether, something that definitely played into the hands of the renewed elites. This process, a source of sorrow for leftists, is historically explicable. Something similar happened with postmodernist theories: conceived by the post-war radical intelligentsia as a weapon for subverting traditional “white” and masculine conceptions of the world, they forfeited their own revolutionary sense when the radical movement collapsed. They have rather developed into a new intellectual fashion that irritates activists insofar as it is distant from their everyday practices and in some regard really does function to preserve the status quo.

Ivan Ovsyannikov // A Leftist Response to the Immigration Question

First published at https://www.ikd.ru/node/17246

A Leftist Response to the Immigration Question

Russian Marxists do not often raise the issue of immigration. When the latest explosion of anti-immigrant passions puts the issue on the national agenda, leftists as a rule limit themselves to general declarations in the spirit of internationalism and humanism. However, a simple refutation of xenophobic myths or stating the obvious truth that the problems associated with immigration are the product of capitalism is not enough to counter nationalist propaganda and prejudices. A program is needed that would oppose both right-wing and neoliberal “solutions” to the issue of immigration.

Divide and Conquer: Xenophobia and Labor Market Dumping

The encouragement of xenophobia amongst workers is one of the oldest and most effective strategies employed by the oppressors. How it works is easily shown by a simple example from trade union practice. A South Korean corporation that produces automotive parts built a plant in a depressed area of Russia beset by chaos and unemployment. Faced with hyper-exploitation, the violation of elementary labor rights, and the boorish attitude of their foreign and Russian managers, the workers at the plant decided to organize a trade union. Using intimidation and repressive tactics, company management squashed this attempt at self-organization, thus reducing the number of trade union members to an isolated handful of activists. However, one of the main deterrents was the threat of mass layoffs and the hiring of “guest workers.”