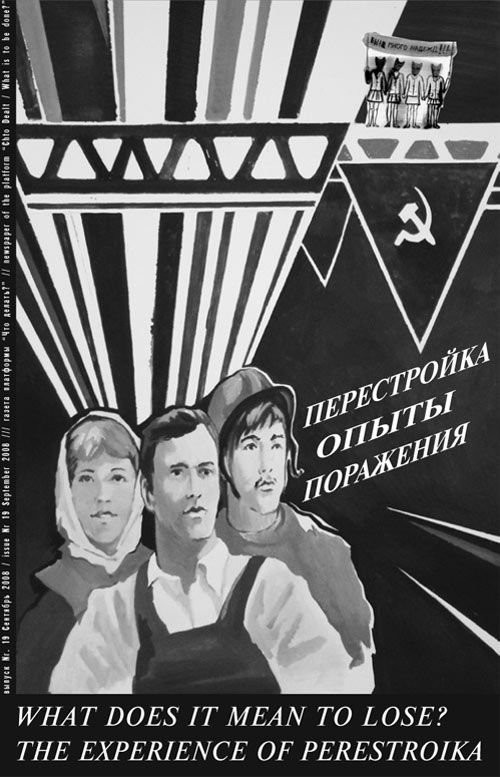

#19: Experience of Perestroika

Perestroika Songspiel & Chronicles of Perestroika

Perestroika Songspiel

Project authors: Chto Delat? Olga Egorova (Tsaplya); Dmitry Vilensky; Natalia Pershina (Gliuklya); Nikolai Oleinikov

Director: Olga Egorova (Tsaplya)

Composer: Mikhail Krutikov

Screenplay: Tsaplya, Dmitry Vilensky, Gliuklya

Camera and lighting: Artem Ignatov

Sound: Sergei Knyazev

Set design: Nikolai Oleinikov, Dmitry Vilensky

Our project deals with a key episode during perestroika in the Soviet Union. The action of the film unfolds on August 21, 1991, after the victory over the restorationist coup. On this day of unprecedented popular uplift it seemed that democracy had won a final victory in our country and that the people should and would be able to build a new, just society.

Olga Egorova (Tsaplya) – Dmitry Vilensky – Natalia Pershina (Glucklya) // Perestroika-Song. Victory over the Coup

21 August 1991

Characters

A Democrat

A Businessman

A Revolutionary

A Nationalist

A Woman

A Chorus (men and women in traditional choir costumes)

A Group of Wolf-Girls (young girls in school uniforms and wolf masks who intervene in the action from time to time)

Scene 1

The Chorus sings the introduction. Behind them we see a cityscape with a stormy sky above it.

Weve come to tell you the story

Of hopes that didnt come true

Of promises that werent made good.

Here are five heroes of perestroika,

Five heroes of perestroika.

Today they are the masters of history,

They are making history:

An idealistic democrat,

A noble businessman,

A heroic revolutionary,

A bitter nationalist,

And a woman who has found her own voice.

Today they believe that together they can build

A new, just society.

Tyranny has fallen!

The communist regime will never return.

Theres no going back to the past!

Theres no going back to the past!

Whatever the future holds, it will be better than the past,

Better than the past. . .

We will tell you the story

Of hopes that didnt come true

Of promises that werent made good.

Dmitry Vilensky // Introduction to “Victory over the Coup”

The true picture of the past flits by. . . These words by Walter Benjamin have the most direct bearing on the phenomenon of perestroika.

A choir of contemporaries is attempting to construct a comfortable image of perestroika as an irreversible movement toward capitalism. This image serves the needs of the squalid powers that be and thus legitimates the paltry existence of the choristers themselves. To interrupt the flagrantly obscene din raised by these voices, it makes sense to turn to the central question that Benjamin asks in his theses on the concept of history: who is the subject of history? For those who accept the task of continuing the struggle for emancipation, the answer to this question is unambiguous: the struggling, oppressed class itself. That is, the class-as-multitude that clearly realizes and rejects the existing order of things, which fetters our lives, dreams, and the dignity and strength of constituent labor. That is, all those who still remember the pride of belonging to the human struggle for freedom.

Dmitry Vilensky // What’s Next after Next? Commentary to a film/discussion

A conversation about Next Stop Soviet; political naïveté; what it means to experience defeat; exhaustion and humanism; who changes the world; vanity and visionaries; how to keep your ear to the ground; and the challenges that each generation faces.

Next Stop Soviet was a Scandinavian initiative that organized the visits of thousands of young Scandinavians to the Soviet Union in 1988. The idea was to continue breaking the isolation of the USSR through manifold human and cultural exchanges. The outcome was that five thousand Danes went to the USSR through more than one hundred different projects. The Danes lived in private homes with young people with the same interests or occupations as their guests. Among the hosts was Dmitry Vilensky, a member of Chto Delat? It was his first contact with foreigners.

Ungdomshuset (“Youth House”) was the popular name of the building formally named Folkets Hus (“House of the People”), located on Jagtvej 69 in Copenhagen. It functioned as an underground scene venue for music and a meeting point for various leftist groups from 1982 until 2007, when it was torn down. Due to the ongoing conflict between the municipal government of Copenhagen and the activists occupying the premises, the building has been the subject of intense media attention and public debate since the mid-nineties.

What is the task of this film? That’s a good question, the right question. Cinema has long faced the task of how to film a political seminar. The task has been solved in different ways: the famous discussion scene in Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point or the lecture scene in Godard’s La Chinoise established a certain approach to filming such things.

Perpetuum Mobile // A Vehicle from Plan A to Plan B, where Plan B is said to not Exist

Time is like a river that flows endlessly through the universe,

and you could never step into the same river twice…

Heraclitus (attributed)

As a network vehicle, Perpetuum Mobile brings together multiple fields of art, practice and enquiry that exist in disparate institutional frames and territories acting as a conduit and engine for new forms of knowledge, organisation and imagination. Less than a year ago, Perpetuum Mobile didn’t exist. Perhaps, as its counterpart in science, its ideal never will. As a real-world vehicle, however, it has been set in motion

Among its driving ideas, is the ambition to re-think certain basic historical, institutional as well as theoretical paradigms which have been in one way or another compromised, falsely delimited or obfuscated at the present historical juncture. One way to bring something genuinely new into existence, is finding ways in which to re-write the rules of the game. It is best to proceed by way of example.

Boris Kagarlitsky & Artemy Magun // The Lessons of Perestroika

Artemy Magun: I think it is important that you and I talk about perestroika. First, because you were an active participant in perestroika and, from the viewpoint of our group, you are one of the few activists who have remained faithful to its emancipatory content. Second, because you and I both basically subscribe to the same assessment of the current conjuncture in Russia, although we part ways when it comes to perestroika. I have argued that it was a kind of revolution; while in your groundbreaking book you call it a restoration.

Twenty years separate us from the events of perestroika. That is a fairly long time historically: it is the same amount of time as separated perestroika itself from the end of the Thaw, in the Soviet Union, and the events of 1968, in Western Europe. However, the specificity of these serious historical events rests in the fact that they don’t contain their own meaning. Rather, this meaning is determined gradually and post factum, depending on how history unfolds after the events. Thus, as it fades gradually into the historical past, perestroika appears different today than it did twenty years ago. Its destructive, catastrophic import (something that only hardcore retrogrades insisted on during perestroika itself) has become obvious, as well as the fact that, although they actively helped Russia in the nineties, the western powers had an egoistic stake in weakening the country and returning it to the international “semi-periphery.” In their assessment of perestroika, your own works vigorously employ the broader historical context-both the internal history of the October Revolution, which perestroika consummated, and the history of Russia as a “peripheral empire” whose historical legacy was continued by the Soviet Union in its later phase.

Yevgeniy Fiks // Is Sots Art an Art of the Political Right?

Over the last couple of years several photo albums came out on the unlikely subject of Russian criminal tattoo. These albums, narrating about the Self, body, and totalitarianism, document the marginal yet incredibly powerful visual subculture of the late-Soviet Gulag. Beyond relative visibility of underground Soviet dissident inteligencia of the 1960-1970s, beyond forged by Moscow-based foreign correspondents definition of Soviet dissident art, these amateur artists of the Gulag engraved bodies of their human canvases with striking by any standards images of grass-roots anti-totalitarian resistance. The owners of these tattoos of outmost anti-Soviet sentiment and grotesque (top Soviet politicians portrayed as pigs or Communist slogans mixed with foul language) for the remainder of their live span became carriers of best examples of truly direct, political, and uncompromising dissent Soviet culture ever produced, and in comparison to which forever pale the most radical works of Soviet non-conformist artists, including Sots Art, looking like toothless jokes for the middle-class at best.

Dmitry Golynko-Volfson // Between Two Perestroikas

The two decades that separate perestroika from the present have practically not produced a coherent, articulated interpretation of the eras reforms. The attitude of popular consciousness (both enlightened and obscurantist) to this contradictory period is most often suspicious, sometimes to the point of cynical indifference. This attitude probably stems from the emotional hangover that set in after the historical loss that perestroika is (mistakenly) portrayed as in the cultural mythology, rather than being the outcome of a rational effort to understand its causes and effects. In a word, perestroika has not yet been vouchsafed either an exhaustive or a plausible reading. It has seemingly been suspended in an interpretive vacuum as if its case were closed or not amenable to comfortable discussion. A subtle critical-historical analysis of perestroika serves no one, for none of the ruling elites, current and former, has taken responsibility for the severe shock of perestroikaneither its communist organizers nor the liberal reformers nor Putins neoconservatives. In order to somehow compensate the historical illegibility of perestroika, Russian society has become accustomed to seeing it as a traumatic zone of oblivion that separates Soviet totalitarianism from post-Soviet neo-capitalism. The status of a scorched no mans land foisted on perestroika has paralyzed the new generation from justly reproaching the preceding, perestroika generation for its flagrant historical irresponsibility.

Elena Zdravomyslova // Perestroika and Feminism

I learned to say no early in life. And calling oneself a feminist is equivalent to saying no to this society.

Most people believe that feminism came to Russia from the west, that there is no native political and cultural ground for it. But this is not the case. Rather, Russian feminism is simply an unpopular intellectual and cultural movement, which nevertheless has its own agenda and, moreover, its own discontinuous native traditions. Contemporary Russian feminism began to take shape, both intellectually and politically, during perestroika. Although before this time there were also specialists in feminist theory in the Soviet academic community. Sociologists studied the problems of gender inequality and sexual emancipation, and the stories and essays of Russian feminists collected in the anthology Women and Russia (1979) were published in samizdat.

Alexei Yurchak // Mimetic Critique of Ideology. LAIBACH AND AVIA

You can only effectively parody something,

If you like it quite a lot as well

Brian Eno, discussing the work of AVIA

By the early 1980s, Soviet ideology had experienced major transformations. It became irrelevant whether one believed or disbelieved the ideological statements of the system, provided that one experienced these statements in the public sphere as immutable. In this context, a new type of critical engagement with ideology emerged instead of contesting ideological dogmas, as was practiced by the dissidents, it was based on the imitation of ideology. We may call this method, mimetic critique of ideology. Mimetic critique was not designed to expose the falsity of ideological statements of the system, rather it showed that these statements no longer needed to be read for literal meanings and their that task was to create the experience of their own immutability (Yurchak 2006). The method of mimetic critique became particularly widespread among informal artists, musicians, and other members of such circles. Central to this method was the aesthetic principle of overidentification with ideology the exact replication of the form of ideological symbols and enunciations, with a major shift in the meaning that they conveyed. This method had a few advantages over direct opposition to the system. First, the state could easily identify and isolate any oppositional discourse as anti-Soviet, while recognizing the discourse of over-identification as a form of opposition was difficult by definition. Second, this approach did not require one to reject all things Soviet as immoral, which allowed one to conduct the critique of Soviet ideology without automatically critiquing the communist project as such.