The medical commission said A little prayer to their maker, Which done, they dug with a holy spade The soldier from god’s little acre, When the doctor examined tlie soldier gay ‘Or what of him was left, He softly said: This man’s I-A, He’s simply evading the draft,

Bertold Brecht. Legend of the Dead Soldier, 1918

I found out that there is a war on between Russia and Ukraine at a small gas station, where I met some Ukrainians who like me were traveling across Europe by car. Neither Russian nor European nor American media had made any mention of real military encounter between our countries, and so it was hard to believe these agitated women when they told of atrocities committed by Russian occupants on Ukrainian soil. They seemed like yet another element of brainwashing, just like the reports of Ukrainian Nazi atrocities that flooded the Russian media against the backdrop of the annexation of Crimea, only now with a Ukrainian accent – a mirror image of aggressive propaganda from the other side of the conflict. Our’s was a meeting on neutral territory, so to speak, somewhere in the middle of a generic Europe. The womens’ tone toward me was unfriendly, even accusatory; as if being Russian automatically made me guilty of the atrocities they were describing. At some point it even seemed that they were screaming at me. Yet their stories of welded-shut zinc coffins returning “from the East” etched themselves into my mind.

Vlada Ralko – from Kyiv Diary, 2014

It was late May, three months before Ukrainian security forces captured ten Russian paratroopers in the village of Zerkalny in the Donetsk Region. Putin’s response to the question of how Russian soldiers found themselves on the territory of a neighboring country was that they “got lost because there is no clearly marked border there,” but the presentation of military personnel was a living proof that forced even the official Russian media to utter the word “war” – though the Russian and Ukrainian presidents immediately rushed to sign a ceasefire agreement, as if to end the war before it had really even begun.

Then again, the war actually started long before Russia’s secret incursion into Eastern Ukraine. The war came to the Maidan with the first nationalist slogans, and it came to snuff out the revolution. Rabid nationalists were the ones who brought war as they wrecked statues of Lenin. The nationalist turn of the Maidan repressed the movement’s social content, while the ensuing war has frozen any potential flare-ups of class struggle. As Georges Bataille wrote in 1933, fascism arises to put an end to the nascent worker’s movement. Today’s wars remain true to the same goals, which is why in countries that the first world customarily calls “non-democratic” –meaning, poor – social and political protests become ethnic conflicts so quickly.

“They’re showing us cartoons,” said my friend the day Putin flew to Minsk to discuss the conditions for settling the situation in Ukraine. The next morning, I was sitting in an airplane, greedily reading Russian newspapers, trying to understand (in vain) what it was the presidents had agreed upon. It was a secret that this newly printed matter could not reveal, even if it still smelled of ink, and neither could Eugene Thacker’s great book on the horror of philosophy, which I read on the plane. Real horror was here, nearby; an invisible, cold horror between the lines of the morning papers, which told of the meeting between presidents and of ten living soldiers who lost their way into Ukraine in uniforms, with weapons and documents, yet not a word about hundreds or even thousands of dead.

This is when I remembered the Ukrainian women at the gas station and their stories of welded-shut zinc coffins, which I had had trouble believing because they voiced what the newspaper won’t tell you. A chance encounter on the road with these ladies is just part of the rumor mill, and hardly an authoritative source of information. To be believed, facts must be revealed and confirmed by official sources presenting incontrovertible proof.

We usually only believe whatever has been publicly recognized as fact, forgetting how many stringent filters reality passes through to reach that stage – the stage of cartoons made in Russia, Ukraine, America, or Germany with puppet presidents and the politics of the countries they represent. Such cartoons never show welded-shut zinc coffins with dead soldiers. They only show living soldiers, who, in the very last instance of the official Russian media spectrum, were after all only lost (maybe it’s comedy we’re unconsciously looking for in cartoons, and not truth, and that’s what gives them their strength).

In a way, they really were lost: according to the few witnesses, many of the Russian soldiers were convinced that they were being sent to some region of Russia for exercises, only grasping that they were in Eastern Ukraine when the hail of bullets began. Conscripts get lost while following some murky order, as do contract soldiers, who also don’t understand to the full where and why their division is moving; they are ideologically lost, succumbing to patriotic hysteria and throwing themselves into battle with any enemy indicated by mass propaganda, itself especially intolerant in times of war.

Entire divisions get lost with “one-way tickets” to enemy territory, only coming home as “two hundreds.” Cargo 200 is the general name given both to fallen Russian soldiers and the zinc coffins in which they come home from the war, as if death had welded body and coffin together in zinc, turning both into one singular dead weight. Precisely this dead weight is the main material remains, the indisputable evidence, and the only reliable physical proof of war. War is nothing but an assembly line for the production of corpses. Cargo 200 is the principal immediate material product of the war, impossible to consume, while fresh graves are the trace it leaves on the earth.

Such dead weight is a serious problem in an undeclared war. The dead, like the living, have a formal status, upon which the claim of the living over their dead bodies depends. If there is no war, there are no soldiers. Lacking any formal status as participants in an armed conflict and any right to burial by the state, municipal services in Kyiv refuse to provide funeral services free of cost to Ukrainian fighters in the Anti-Terrorist Operation, placing the burden of their burial on the shoulders of relatives and concerned citizens.

In the case of the Russians, matters are even more complex: “two hundreds” return from Ukraine, and according to the official version, were either somewhere else entirely, at exercises in Russia’s regions, or they had resigned or were on leave; in a word, lost, but not fighting on their neighbor’s territory. Identified or unidentified, what to do with this cumbersome burden? As a rule, the unidentified are buried in mass graves in war time, and their families receive funerary notices or letters that their loved ones are missing in action, while identified cargoes 200 are given over to their families for burial. But what do you tell the families if there is no war, and where do you put the unidentified bodies?

In other words, as the state wages its undeclared war, it faces the same question as the classical killer: what to do with the body? According to the different versions and eyewitness accounts that don’t always pass the filters of cartoon reality and official verification, some bodies come home (some of the white lorries in the humanitarian aid convoy drove to Ukraine empty but returned with cargo 200), others stay on Ukrainian soil, buried on the spot, and still others have it that the Russian Army has bought mobile crematoria: special trucks on a Volvo frame for the quick and safe disposal of biological waste (such as the corpses of homeless animals or infected cattle).

The undeclared war announces itself when conscripts and even more contract soldiers stop sending news to their loved ones. Some relatives mobilize, joining forces to search and collate information, organizing communities and committees, and soon the Soldier’s Mothers organization is part of the foreign agent’s blacklist. Some are found, others are not. Some continue to wait, others receive their ‘two hundreds. Families meet and bury this cargo. Its point of origin is unknown, the only explanation a short note: “died while executing his military duty.” The official explanation says they died in their own country – on maneuvers, in exploding gas mains, and in other accidents – but there is no proof of war more solid than these identified two hundreds, their coffins, and their graves, whose number is steadily growing: in wartime, the army literally goes underground.

Not only the army, but the civilian population too goes underground. Those who have nowhere left to run go down into the basements, pedestrian underpasses, and bomb shelters left over from the Second World War, with their children, mattresses, cats, and stools. Civilians hide from death in bomb shelters, while soldiers hide in foxholes and trenches. Dead soldiers hide in graves. Basements, underpasses, bomb shelters, bunkers, foxholes, and trenches are all anterooms to the grave; places where you look for final peace and shelter from the cold terror of the war raging above. Under a world at war, the mole of history burrows its tangled labyrinths, where, as in a nightmare, you go from one space to another – from the bomb shelter to the bunker, to the trench, into the basement, and finally, into the grave.

The grave is the final and ultimate bomb shelter; no one will wound, beat, or hurt you, it would seem, but even here, there is no rest for dead soldiers. Even the presence of their bodies as evidence of war rarely reaches the stage of official and verified information. Journalists try to get in touch with relatives and risk their lives in attacks by unknown assailants during visits to cemeteries to check the headstones on freshly dug graves – this, in fact, is one of the stringent filters that grinds reality into a cartoon – while the families suddenly fall silent or undergo strange metamorphoses.

“Dear friends!!!!!!!!!!! Lonya is dead and the funeral is at 10 a.m., services at Vybutky. Come if you want to say goodbye,” writes a 29-year-old paratrooper’s wife on her page in the social network VKontakte, leaving her telephone number for friends to get in touch. The page is removed the very next day, but some journalists manage to make screenshots and call the number. The wife hands the phone to a man who introduces himself as Lonya and says that he’s alive and well, ready to dance and sing. Of course, telephones can be taken away. Of course, a woman is easily put under pressure. Still, there is something about the very idea of a telephone conversation with somebody whose name we saw written on a gravestone (until they took off the nameplate), the very possibility of a singing, dancing zombie at his own funeral, having returned to his wife from a place from which there is no return. Call it an evil cartoonification of truth.

In Alexei Balabanov’s film Cargo 200 (2007), a girl falls into the hands of a militiaman who turns out to be a maniac and ties her to the bed in his apartment. She is waiting for her paratrooper-fiancée to come home from Afghanistan, but the fiancée comes home as a cargo 200. As an official, the militiaman is given custody of the zinc coffin, brings it home, opens it with an axe, and throws the corpse onto the bed next to the girl with the words, “Wake up, your groom is home!” The girl is left to lie on the bed next her decaying, fly-eaten bridegroom. The action takes place in 1984, exactly thirty years ago, during the war in Afghanistan, which is when the term “cargo 200” first emerged, be it in reference to the number of the corresponding order of the Ministry of Defense of the USSR (Order No. 200), or the normed weight of transport containers carrying the bodies of military personnel (200 kg).

Two hundred kilograms is the weight of the entire “transportation container,” a tightly shut wooden box. According to the transportation regulations, this box contains a wooden coffin. The wooden coffin contains a zinc coffin, hermetically welded shut, which, in turn, contains the dead soldier’s body. Even such a package isn’t lasting or reliable enough, it seems; not only living paratroopers get lost, but the dead also continue to wander around. They come home to the beds of their brides, like in the 1984 of Balabanov’s film, or return to their wives and families to take care of them, like in our own 2014.

It is usually the poor who become soldiers, those who have nothing to offer except for their own lives or the lives of others in exchange for a piece of bread and a roof over their heads and those of their loved ones. How else can a state fighting an undeclared war get the silence it wants from the recipients of that dead weight? “As a rule … military personnel are the main breadwinners. There’s such a thing as a ‘military mortgage’ – if a soldier resigns from the army on his own will, the Ministry of Defense stops paying for his apartment… So the unit’s commanding officer will come to the widow and say, your husband fell in action, and we’re ready to pay you and leave you the apartment. But the death certificate will say that he died in some place other than Ukraine,” regional Pskov Yabloko politican Lev Shlosberg explains. Mortgages, subsidies, compensation packages: that’s how dead soldiers continue to feed their families.

In his story “Sherry Brandy,” writer and Gulag-survivor Varlam Shalamov describes poet Osip Mandestam’s death in the camp. The poet dies drained of all strength, wasting away from the diseases of the camp. He gets his camp rations and greedily starts tearing away at the bread with scorbutic teeth, bloodying the bread with his bleeding gums: “By evening he was dead. They only registered it two days later, because his inventive neighbors succeeded in receiving the dead man’s bread for two days in a row, with the dead man raising his hand like a marionette. It so happens he died two days before his date of death, a detail of no small importance for his future biographers.”

There is a certain economy, according to which the dead continue to feed the living or take part in their affairs in some other way. Once a corpse has entered this economy, it is neither alive nor dead. The “cargo 200” of the undeclared war is acquired in the border zone between life and death, together with vampires, zombies, ghosts – all those for whom death holds no rest. They didn’t die in Rostov, and they didn’t die in Lugansk, but somewhere between Russia and Ukraine, on the unmarked border, where they are still lost and continue to send signals and care packages from their shady border zone, the zone of undeath. The dead soldier’s corpse is firmly embedded into a machine distributing mortgages and care packages. It only seems as if capitalism, for once, was blameless here. In fact, capitalism feeds itself with the corpses that wars will produce. That is the non-medial underbelly of the “war of sanctions,” with its economic character and its political effects. In the dull grey zone of capital’s material reality, the body wanders from one death to the next.

On July 17, Malaysia Airlines MH17 en route from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur met with disaster. The Boeing 777 passenger jet crashed near the Ukrainian village of Torez approximately eighty kilometers from Donetsk, killing all 298 people on board, including fifteen crew members. In the course of the extended investigation that followed, different versions were presented. American and Ukrainian sources claimed that the plane was shot down with a surface-to-air missile by the separatists/terrorists in control of the Lugansk and Donetsk regions and armed by Russia, while the Russians insisted that the plane was probably attacked by the Ukrainians in the air or was even shot down by the Americans themselves in order to later place the blame on Russia as a pretext for a new Cold War, or that a Ukrainian air traffic controller sent the plane via a dangerous route on purpose, etc. Either way, Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 was out of luck; it found itself in a zone of never ending combat and constant attacks from the air, and its crash became the most obvious confirmation of the undeclared war with international stakes high enough to permit its association with the cold one.

The most exotic version, however, came from the then leader of the terrorists Igor Strelkov/Girkin, who claimed that the passengers of the crashed Boeing had died several days before being shot from the sky. This claim was based on eyewitness accounts from separatist fighters who had gathered up the corpses and claimed that they weren’t “fresh” and even bloodless, as if the plane had taken off in Amsterdam with strange cargo: frozen corpses standing in as living passengers strapped to their seats. Some conspiracy theorists even ventured that it was the same Malaysian Airlines Boeing that disappeared without a trace this March, possibly even with the same passengers.

This version was clearly taken from the British series “Sherlock,” where a plane is loaded with corpses to be blown up in midair in order to provoke an international conflict, and it stands out for its fantastic absurdity and its clear contradiction of any principles of reality. However, beyond the principle of reality, the madman proclaims a strange truth: he tells of the airline of the world, where we are all passengers, seatbelts strapped on tightly. Madness is also reality, albeit communicated through a series of metaphors. In this version – let’s not call it crazy, but metaphorical – the passengers of the Malaysian Boeing literally died twice. The catastrophe of which they were victims is preceded by another catastrophe, and thus unto infinity: the plane keeps crashing to the ground, turned into debris by the war, and the passengers are gathered up, frozen, and strapped back into their seats.

“And not even the dead will be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious,” writes Walter Benjamin in his sixth thesis on the conception of history. And the enemy is victorious. Not us and not them, but only the enemy is victorious in this war of attrition. The war as an endless series of enemy victories is not cold because no blood is shed – blood is not shed only in cartoons on a war of sanctions, whose viewers bemoan the loss of their beloved Italian cheeses or their civil rights or rejoice at the appearance of a new bold superpower on the map of world politics.

The war supplies new positivity to the circulation of global capital at a time of crisis (which, as Rosa Luxemburg noted, is organically connected to the expansion and violent struggle for markets). It is cold with corpses whose integrity is compromised, who are killed and frozen, just to kill them all over again. They are lost in the time-loop of death, in a grey of bad infinity much like the Hindu circle of samsara. But unlike samsara, the circle of reincarnation, our cold war is a loop of endless “re-dyings,” and it’s just as hard to get out. The economy of war is based on the capitalization of death and it inevitably implicates all members of society, whose relative peace and quiet is only sometimes disturbed by ominous returns of lost and dead soldiers who are still ready to go to battle for an enemy victory. Once they are resurrected, there will finally be peace in our cemetery.

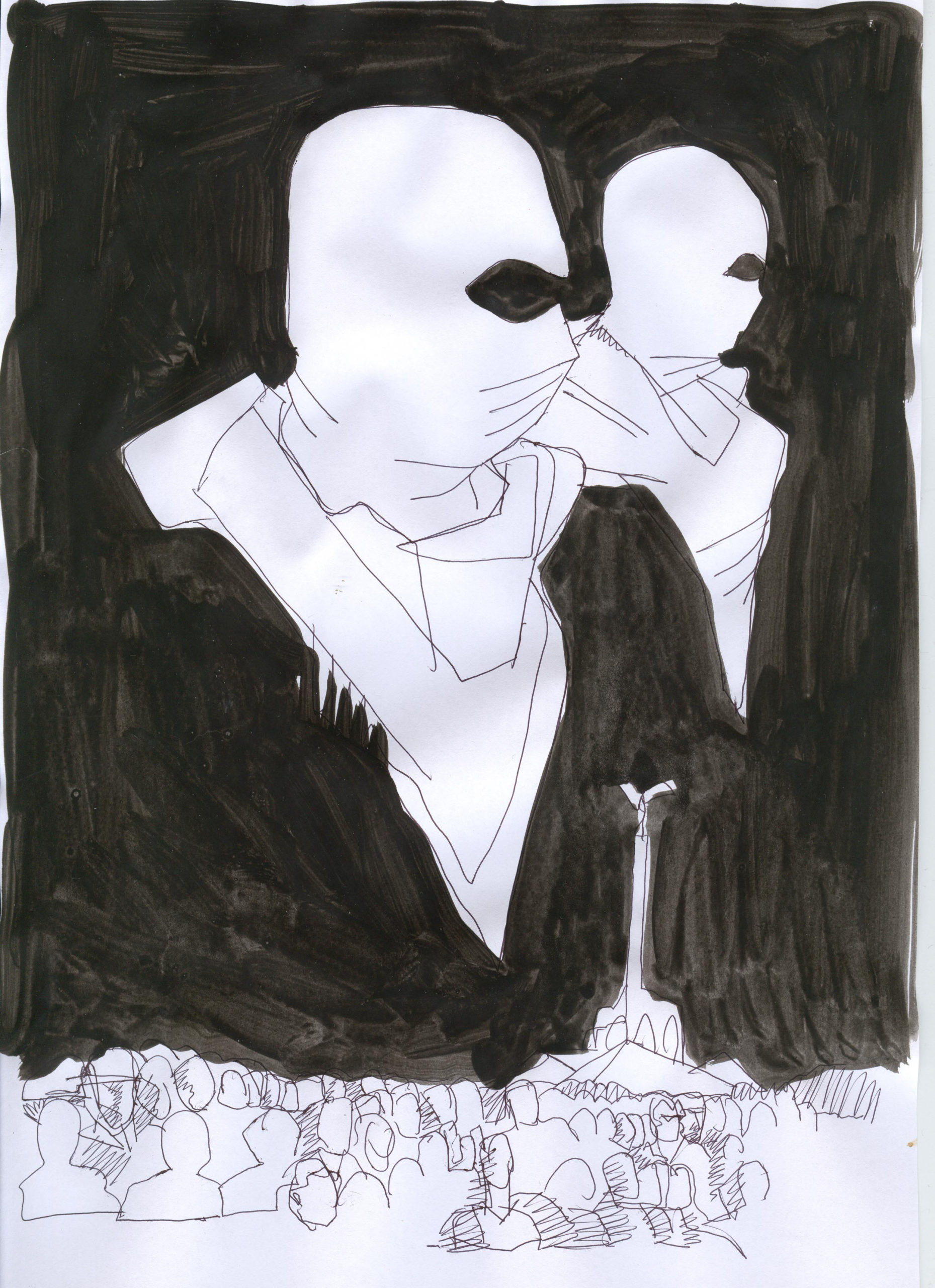

The article is illustrated by stills from the film Cargo 200 (2007) by Alexei Balabanov.

The Russian original was first published at www.openleft.ru.

Its English translation was comissioned and published by the Academy of the Arts of the World, Cologne (www.academycologne.org).