It is difficult to write about Putin’s Russia, something one does reluctantly. One hesitates to use the word Putin because by this act alone you intrude into the political arena, where your least utterance doesn’t remain mere hot air but can also turn on you and make you regret what you’d said. I do not have in mind “conspiracy theory,” however, but the specific shift in Russian political sensibility that has taken place before our eyes. A hypersurplus of mutually repetitive utterances has now been stockpiled, and their lack of content underwrites their existence in the mediaverse. It is simply impossible to listen to them any longer, just as listening itself has become a chore.

It is difficult to write about Putin’s Russia, something one does reluctantly. One hesitates to use the word Putin because by this act alone you intrude into the political arena, where your least utterance doesn’t remain mere hot air but can also turn on you and make you regret what you’d said. I do not have in mind “conspiracy theory,” however, but the specific shift in Russian political sensibility that has taken place before our eyes. A hypersurplus of mutually repetitive utterances has now been stockpiled, and their lack of content underwrites their existence in the mediaverse. It is simply impossible to listen to them any longer, just as listening itself has become a chore

It is not so much the political situation (in which power, capital, and the mass media are concentrated in one and the same hands) that I would like to discuss, as it is the “nonpolitical” situation. When we examine the zone of the nonpolitical, the lifeworld of the ordinary man, however, politics is, all the same, one of the conditions that shape it. Politics has long since ceased being something in which people take part; instead, it has become something that shapes people. It has ceased being a clash of parties, social groups, views, and convictions; it has ceased being a concern only of the state and its institutions. Politics courses through our bodies-bodies that vote, work, watch TV, sit in cafés, smoke cigarettes, sleep, die, etc. Politics has long ago become biopolitics.

Many still remember (although the mass media have done everything they can to make us forget) the romantic period when the experience of an anarchic democracy without the institutions that democracy depends on became part of our lives. In turn, the spontaneity and popular character of the democracy in the late eighties and early nineties might not have manifested themselves had not revolt become a vital necessity in Soviet times (especially during the Brezhnev years).

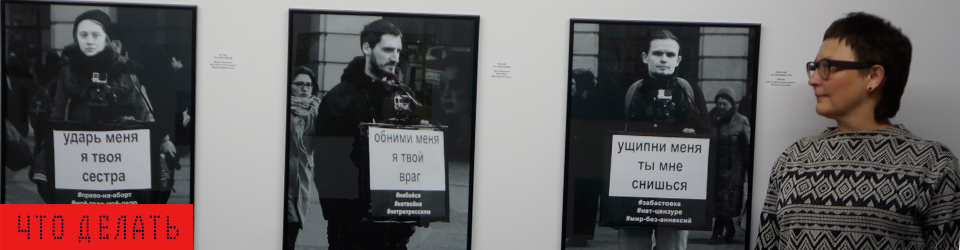

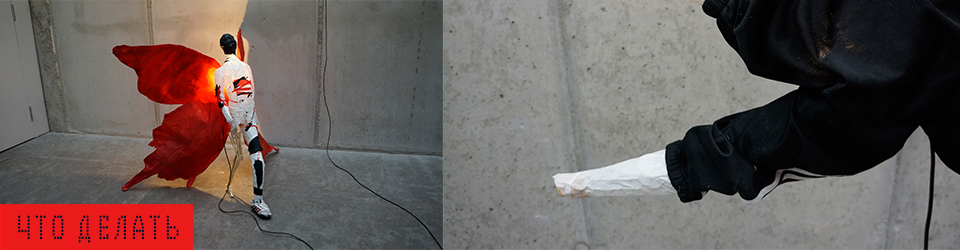

Revolt is a resistance of bodies that marks the limits of biopolitics.

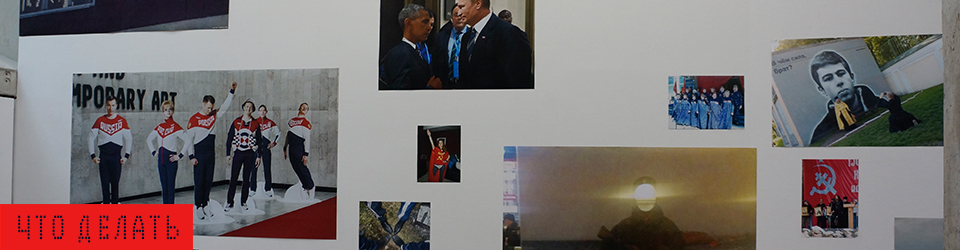

At the end of the Soviet era, the word democracy became the symbol of this revolt. Then democracy began to be built, and its shortcomings, aporias, and weak points were revealed. This is all more or less obvious to the critics of the western model of democracy. Institutionalized democracy, of course, is a rather refined control mechanism, but Russia’s puppet democracy has acquired a service class that far outnumbers the standing political bureaucracy. This is mainly a new generation of people, most often young people, who don’t remember even the early post-perestroika years, much less Soviet times. As opposed to many members of the older generation whose service to the current political authorities is wholly cynical and who have happily forgotten what they said a decade ago and what they believed in (perhaps sincerely) two decades ago, the “new” people have already been formed as political bodies per se.

Thus, a certain young writer (Anastasia Chekhovskaya) gives a rapturous account in Izvestia of her meeting with Putin. She relates how glad she is that the state has commissioned her to educate the populace, to teach them “good feelings.” Then, without batting an eye, she calls these same people lumpen who have been mutated by mass culture and almost openly declares that it is “young people” (like her) who are the new elite.

Or take our contemporary artists. Their state commissions haven’t come through yet, but they’re already searching for the right people to serve.

And then there are other “young people,” the members of the Nashi (Ours) movement. Dressed in identical team jackets (it’s clear who footed that bill), they are bused in organized fashion to pro-Putin rallies. Guarded by the police, they sing songs and yell patriotic slogans at the same time as, on the other side of Tverskaya, the OMON beats the March of the Dissenters with billy clubs.

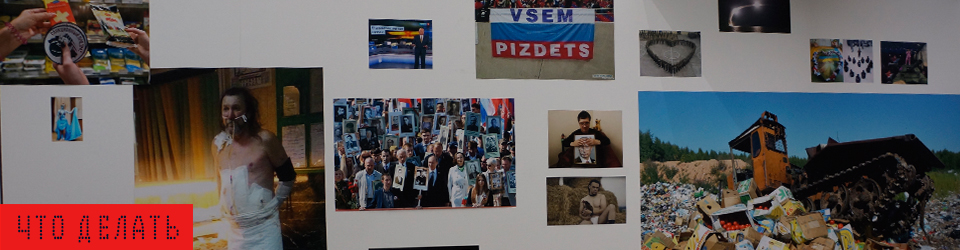

These are not simply examples of “grassroots political activism.” There is nowhere that such activism could emerge from: the time is not disposed towards it. This is a new social space that has taken shape precisely in the last several years: we might describe it as an open call for a place in the sun. Only there is no search committee and no list of qualifications for the jobseekers. It is probably not even a job competition, but rather a show in which only the most cynical end up in power or on the tube. All the other applicants master the art of “natural cynicism” (the ability not to see pain, humiliation or the trampling of liberty), expecting a summons to serve in the most miserable “bureaucratic” (in the broadest sense of the word) postings, where these mid-level satraps will employ their skills with the right amount of zeal.

Graduates of the school of political perceptivity, the new-model individuals have been hatched in record time. This is the type of people Gleb Pavlovsky has dubbed “the victors.” They are instantly recognizable: they are the ones who talk about the “horrors of Yeltsin-era democracy,” who criticize the Dissenters for their lack of a “positive” program, who rejoice over the country’s growing budget and the size of the Stabilization Fund… We could go on. While it would be wrong to say that all these folks are well off, they are already “others.” Even if their grip on power and money is still slight, power and money figure virtually in their way of thinking, in their sensibility. The state needs such people. They are the new (dependent) “power” elite. A semi-powerful elite whose power extends to the moment when they are reminded who made them what they are and how. Semi-victors.

But what is to be done with the losers? What is to be done with those whom we still call ordinary people? With people who keep their counsel and watch TV? (Whether they condemn or support Putin while doing so is unimportant.) With those who protest when driven to their wit’s end, only to be told that they don’t have permits to demonstrate and that the principles of democracy dictate that they should pursue their rights only through the courts?

No one needs the losers. They are not simply forgotten: systematically, for years on end, they have been the victims of a real genocide. Everything points to the fact that it is not only the Anastasia Chekhovskayas of the world but also the central authorities themselves who are waiting for entire segments of the population to become extinct naturally. The lumpen will be the first to go. Then the pensioners. Then the people who for some odd reason continue to give them medical treatment. Then the people who continue to work in small towns and villages for a pauper’s wage. (In this sense, apparently, they expose their “passive” natures.) Then the people who remember something. Those who don’t want to join the jubilant ranks of the victors will be the last to go.

Revolt is a lawless thing. So-called democratic rights-the right to vote, the right of assembly and peaceful protest, the right to strike, the right to have one’s grievances redressed in the courts-are intended to limit the possibilities of revolt. They are mechanisms for regulating social discontent. That is why it is so hard to reject “democracy.” At the end of the day, it is an advantageous form of governance for states, especially those inextricably bound up with big capital. Tyrannies have the habit of crushing revolts, while democracies create mechanisms for controlling them. Aside from protest, however, revolt has another aspect: the stoppage of work. Not just any specific kind of work, but the work of the state itself. Hence, those who relate negatively to all forms of revolt are either bureaucrats or strikebreakers. The former are fond of repeating ad infinitum that protestors should use only legal means to realize their rights. They are hostage to the notion that democracy is a form of the state. In practice, this transforms democracy into a means of manipulation. The latter group (and nowadays the numbers of such people are growing) consists of bodies. They are bodies that have become elements in the state machine (a “powerful” and “successful” machine), whose smooth functioning requires the elimination of all obstacles. The main obstacle is the class of unwanted, superfluous people. It is telling that the bodies servicing the state system constantly regale us with the rhetoric of “positiveness” and “hard effort.” While we’re working, they’re protesting. We draft new legislation, but all they do is hold demos. We’re building the state up, but they’re trying to tear it down.

It is no longer different kinds of politics that clash here, but different ethics. The first ethic is the corporate ethic, which has lately become ubiquitous-the ethic of doing what needs to be done, of usefulness and reliability. The second ethic is the ethic of community. It consists in standing with those people whose tastes, views and ideals you cannot share, with people who are sometimes completely different from you. But you stand with them only because you’re willing to join them in a community based on the experience of injustice, which everyone knows to one degree or another. Not recorded on any scrolls, the community ethic is the continually repressed source that nourishes the idea of democracy. It cannot be eliminated completely, although politics has developed a multitude of instruments to make us forget it. Once you do forget, however, you’ll be forever deaf to the violence that is perpetrated right outside your door-sometimes by your own hand.