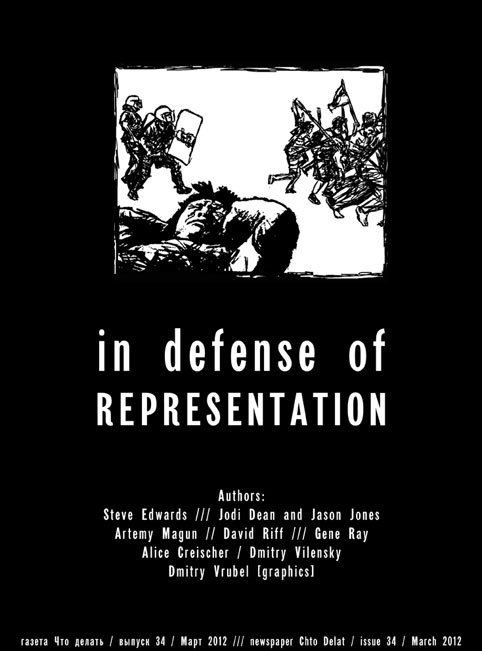

#10- 34 In defense of representation

Dmitry Vilensky // In Defense of Representation

In this issue, we want to show that this problem demands a more detailed analysis.

This is worth doing not for the sake of an academic review of how certain terms are used, but to resolve the most pressing issues surrounding the continuation of emancipatory practices in a world gripped by a serious, protracted crisis when it comes to the emergence of political consciousness. We believe that one should start with the old maxim (whose sense fades with every passing day) that the acquisition of consciousness is the prerequisite of all progress and emancipation, and that all conscious awareness of the status quo and the totality of the world is a representational act.

In the specific historical situation of March 2012, when we are forced to bid farewell to the euphoria generated by the wave of popular uprisings from Russia to Egypt, we see that the “scoundrels are celebrating victory” again (to paraphrase Alain Badiou). And so we try to understand what it is that leads, again and again, to the end of the most brilliant, courageous, radical and honest civic movements. Could it have been otherwise? What should have been done differently? Where were mistakes made? We pose these same questions in the realm of culture. How has it happened that, after many long years of socially engaged art practices, we see that people simply have not noticed their presence and impact on societal life, while the insolent domination of the art market has grown to a previously unimaginable scale, having proven capable of instrumentalizing the most radical forms of politically engaged art.

Gene Ray // Radical Learning and Dialectical Realism: Brecht and Adorno on Representing Capitalism

This set of problems has a history, and Brecht is a key figure in it. If I like others am drawn to Brecht at this moment, it presumably is because the problems themselves point us back to his works and positions. Rereading Brecht, I have kept Adorno open on the table. I have tried to maintain the pressure that each puts on the other, and to think from that tension about the challenges of representing capitalism in art. Brecht’s works were aimed at producing pedagogical effects, at stimulating processes of radical learning. He took art’s relative autonomy for granted but refused to fetishize that autonomy or let it become reified into an impassable separation from life. He based his practice on the possibility of re-functioning and radicalizing institutions and reception situations. Adorno, in contrast, made the categorical separation from life the basis of art’s political truth content. In its structural position in society, art is contradictory: artworks are relatively autonomous but at the same time are “social facts” bearing the marks of the dominant social outside. Paradoxically, only by insisting on their formal non-identity from this outside can artworks “stand firm” against the misery of the given. Adorno’s position is first of all a categorical or structural one; it generally is not oriented toward effects or specific contexts of reception. Except, as will be shown, when it comes to the works of Beckett and a few others. The radically sublime effects that these works ostensibly produce led Adorno to advance them as counter-models to Brecht.

The argument I unfold here proceeds in three parts. In the first, I characterize Brecht’s committed approach to representing social reality as “dialectical realism.” In the second, I reread Adorno’s critique of Brecht, and in the third, I consider Adorno’s counter-models. My conclusions are, first, that Adorno’s critique fails to demonstrate the “political untruth” of Brecht’s work; and, second, that Adorno’s discussion of Beckett, Kafka and Schoenberg in this connection does not convincingly establish a generalized political truth effect for their works and therefore does not establish them as counter-models to Brecht. In any case, the truth effect Adorno claims for Beckett is not one that is oriented toward a radical political practice aiming at a passage out of capitalism.

I. Brecht’s Dialectical Realism

There are many roads to Athens.

– B. Brecht

Brecht’s representations of capitalism are often rough sketches or snapshots of the background processes against which radical learning takes place. Arguably, the learning process itself is almost always the main object represented. Capitalism – including fascism, one of its exceptional state and regime forms – appears as “the immense pressure of misery forcing the exploited to think.” In discovering the social causes of their misery, they discover themselves, as changed, changing and changeable humanity. Seeing the world opened up to time and history in this way, Brecht was sure, inspires the exploited to think for themselves and fight back.

David Riff // “A representation which is divorced from the consciousness of those whom it represents is no representation. What I do not know, I do not worry about.”

There is something uncanny in this quote from Marx, torn out of context and pasted into a fresh document 150 years after it was written. [1] It’s like looking into a mirror where there should be a window. It describes the status quo of our own spectacular world: a massive accumulation of non-representations, all divorced from consciousness. But at the same time, this is a world where self-representation, implying self-consciousness, claims to be everywhere, on mobile devices, in cars, airplanes, and even on remote desert islands. Representative machines previously only available in big clunky institutions are now open for everyone’s use. Consciousness is everywhere as a potentiality. But the pressure is too great. You have to represent. You have to hand in this text. Don’t think. Write. Self-expression before self-knowledge; find the right quick phrase for a certain state of subjectivity, shot out ultra-rapid in a network of friends, where it quickly loses connection to the consciousness that supposedly created it, becoming a micro-commodity, or a firing neuron in some collective mind we do not yet fully understand. Stop complaining. Represent.

Of course, Marx wasn’t talking about representation in the artistic, cultural, or linguistic senses. In these particular sentences, he meant political representation. The quote above comes from an impassioned plea for the freedom of the press in covering the deliberations of the Rhine Province Assembly 150 years ago, one in a series of articles for the Rheinische Zeitung where Marx works through all the linguistic mis-representations and purely unconscious lapses in the available documentation of the closed Assembly’s proceedings. Part of the articles’ polemic program is the battle against direct censorship and other more intricately hypocritical means of keeping the work of government far from the public gaze. Marx is attacking a state that sees itself at a complete remove from its subjects, hovering above them as a police helicopter. We should see. We should know. We should worry. Мarx is demanding transparency.

Artemy Magun // The post-communist revolution in russia and the genesis of representative democracy

“Representative democracy” is, at the moment of its emergence, an oxymoron. Representation, and in any case the electoral representation, has always been considered an aristocratic institution. Rousseau saw it as a “modern”, that is medieval, feudal, form of government, linked to the institution of estates. Representation referred to the estates (even in Locke), or – in Hobbes or Bossuet – to the incorporation of both God and society in the figure of the monarch. The model of Sieyès, where the representatives of the estates were to become constituent power, representing the sovereign nation, merged the two (contradictory) senses of representation together. The oxymoronic formula sends from its both terms away to something else – namely, to the contradiction itself which, far from being since then “sublated”, is perpetuated and may at any time turn its restorative-conservative or radical utopian side. Furthermore, this formulaic tension is in fact a sign of the event which goes beyond the concept but which opens up its internal contradiction and determines the tendency that would prevail for a time.

In general, one may argue that the representative democracy as such is a creation of revolution. Revolution is a point where a society turns against itself, a moment of its internal conflict. But it is also the internal fold where the society aspires to constitute itself from within. The “re-“ of representation is of the same nature that the “re-“ of revolution: both refer to the internal fold of the modern society which, in its political structure, turns toward and against itself . In this context, the “representative” democracy implies an ambivalent attitude to (direct) democracy: here, the democratic politics becomes wary of democracy. Representative democracy may mean a restraint of democracy — as for Hamilton — or democratization of the (hitherto estate-based) representation — as for Sieyès.

Jodi Dean and Jason Jones // Occupy Wall Street and the Politics of Representation

Debates over demands, tactics, and the ninety-nine percent have featured prominently in Occupy Wall Street since the movement’s inception. Movement participants argue over whether Occupy should make demands or whether occupation is its own demand. Activists debate whether the movement should pursue a diversity of tactics or explicitly disavow violence. People with varying degrees of involvement in and acceptance of the most significant political development on the left since the anti-globalization protests ask themselves if they are part of the 99% and what it means if they are. Underpinning these debates is the question of representation. What does the movement represent and to whom?

To present the disagreements simultaneously constituting and rupturing Occupy as fundamentally concerned with representation is already to politicize them, to direct them in one way rather than another, for the question of representation has been distorted to the point of becoming virtually impossible to ask. Strong tendencies in the movement reject a politics of representation. Rather than recognizing representation as an unavoidable feature of language, process for forming and aggregating preferences (always open to contestation and revision), or means of producing and expressing a common will, these tendencies construe representation as unavoidably hierarchical, distancing, and repressive (and they think of hierarchy, distance, and repression as negative rather than potentially generative attributes). For them, the strength of Occupy is in its break with representation and its creation of a new politics.

Steve Edwards // Two critiques of representation (against lamination)

A little story has developed in the circles of the political and artistic avant-garde. It is more often spoken and heard than written and read, but it constitutes the background common sense for much thinking about politics today. This assumption suggests that the critique of representation and the critique of parliamentary representation (bourgeois democracy) are equivalent and coeval. In politics (the Occupy movement, for example) this entails the rejection of any representative or spokesperson, in favour of horizontal decision-making, whereas the rejection of bourgeois formal democracy for some contemporary artists and critics suggests the necessity of an exodus from the bourgeois art world of museums, galleries and all their trimmings. Involvement in this system is imagined to be undemocratic, since it entails working in hierarchical institutions, dependence on capital (whether state or private in form) and assuming to represent, or speak for, others. Autonomy in politics is equated with autonomy in art. Followed through, the alternative would be something like direct democracy in art: soviets of artists, workers and soldiers deputies, which would certainly not be a bad thing. However, the story rests on an imaginative process that laminates distinct critiques (practices and ideas). In order to think about this composite we need to begin by examining the constituent layers.

The first critique

The first critique counterposes direct democracy to parliamentary or representative democracy. Consideration of the state form aside, revolutionary socialists presuppose a basic criticism of parliamentary or representative democracy. [1] Liberal capitalism has bought for the citizens of most western states constitutional rights (formal equality of citizens, freedom of contract, equality before the law, freedom from arbitrary arrest, freedom of assembly and freedom of speech) and universal suffrage (one person one vote, secret ballot, payment of representatives, set terms of office and so forth). In this form of democracy, politicians ‘represent’ blocs of voters, and governments are formed from alliances of politicians in parties. The politicians are usually educated middle-class professionals (often lawyers) and businessmen who are closely connected to their class. Domenico Losurdo has argued liberalism, which constitutes the backbone of this system, is, in fact, a Herrenvolk democracy or a democracy of gentlemen. It is predicated on what he calls a ‘community of the free’, a select group — typically property-owning gentlemen — to whom democratic rights are believed to apply exclusively. [2] The democracy of these gentlemen is a democracy of property. The separation of public and private life is at the core of this politics, with property and economic activity reserved for the private sphere. The democratic gentlemen could be, and often were, slave owners, employers of factory children, domestic tyrants. But for liberalism, these are private matters, beyond the reach of the state. The gentlemen could espouse democracy and uphold slavery at the same time, because slaves were not thought to be part of the community. The same might apply to workers and women. Those outside this elite community had no rights or possessed strictly delimited rights. Capitalism can work perfectly well without democratic representation, but liberal democracy comes with exclusion clauses of its own.