DV+ DR: Solidarity [a word which we owe to the French Communists] signifies a fellowship in gain and loss, in honor and dishonor, in victory and defeat, a being, so to speak, all in the same boat. Trench. Recently I was rather intrigued by a fragment that I found in one interview that Susan Buck-Moriss made with Grant Kester. She said: “This is Adorno’s point when he speaks of the somatic solidarity we feel with victims of socially organized violence, even when that violence is justified in our own culture’s term. So I want to say that aesthetics is the body’s form of critical cognition, and that this sensory knowledge can and should be trusted politically. It is empathy rather than sympathy, because it is capable of producing solidarity with those who are not part of our own group, who do not share our collective identity”.

I would like to suggest this quotation from Susan Buck-Moriss as point of departure in our exchange of opinions on what solidarity is. First of all, I hope that this statement might help us to bridge the traditional socio-political dimension of solidarity with art and the cultural situation in general.

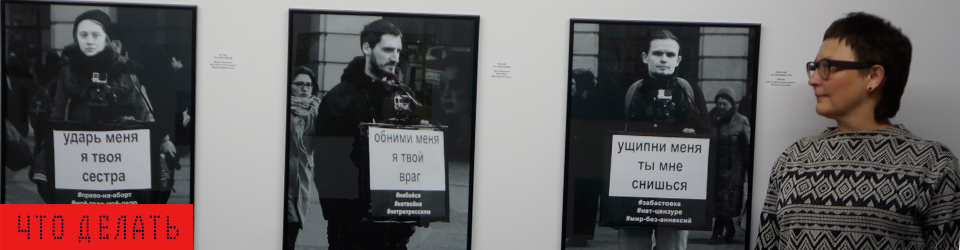

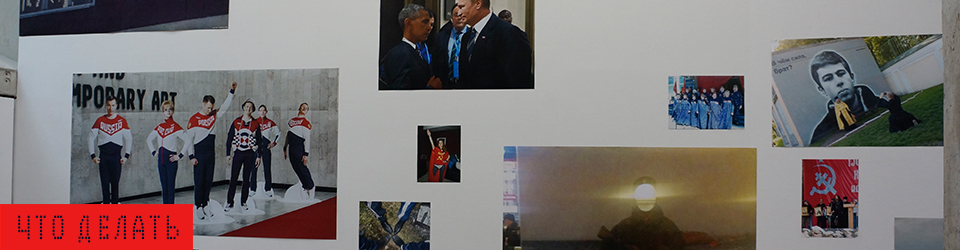

In the sphere of real politics, there are different modes of “showing” solidarity:“Wear this ribbon to show your solidarity with AIDS victims”,or donate some money to support the victims of repression, or go to the demo, or whatever. Of course, just as in political life, cultural workers now find themselves signing different mailing lists and petitions in support of the victims of different type of repression from the side of the state, fundamentalist groups or intelligence services. This happens in the USA (enough to remember Critical Art Ensemble), in Poland, in Russia and so on…

But is this the only procedure for the demonstrating solidarity? And what are its limitations?

Moreover, the call for solidarity is often an appeal from a marginal position. What I mean is that it is a way of calling out for support when you are rather marginal in the local political situation and the question of your survival hinges upon your ability to mobilize mechanisms of international support (through funding, cooperation etc.). In this sense, the performance of a call for solidarity is rewarded in some way, out of sympathy. More often than not, the (much-needed) support comes from the system it opposes. The system is not homogeneous and there are always lots of “good guys” who are already inside, who can help you to come in, out of solidarity.

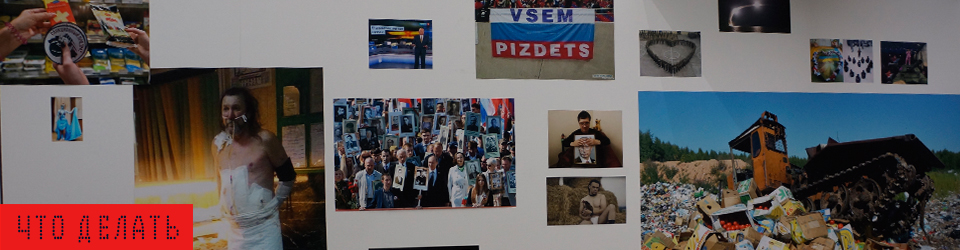

The question is relevant because such “shows of solidarity” often seem dangerously ineffective and crumble as soon as “real life” comes back into play. In recent times, we can hardly remember any relevant protest of cultural workers aimed at breaking the routine of the spectacle. The strike of “intermittents du spectacle” was aimed at keeping old social benefits and did not touch the notion of the festivals they worked on. And there are hardly any effective boycotts of biennales, exhibition-projects or institutional activities worth mentioning; it doesn’t not matter how bad and senseless they are and in which direction they seem to be heading. My experience in organizing such open protests and pushing the organizers to provide the artists with more decent conditions to realize their work have been very negative on the whole. At the beginning almost everyone is saying that the project has no sense, that the organizers are assholes and they see no reason to participate, but finally everyone is smiling and taking part in the event that they were opposing. It seems that you have no way to reveal your protest in our heavily competitive world; at times, it even seems really stupid to stand up against what is “just another show”, especially if this “show” doesn’t place your (cultural) existence in question. And even if you do “show” your solidarity, it often seems like you’re simply performing some speech-act or sympathizing at best, without actually experiencing the somatic solidarity that Adorno is talking about.

Isn’t “a show of solidarity” often just a non-committal performance? And what happens to such shows of solidarity when they are aestheticized? Don’t they become the kind of fake shows of solidarity that pretend to be interactive but wind up being little more that venues for cultural agents to “jump on the bandwagon” and profile themselves?

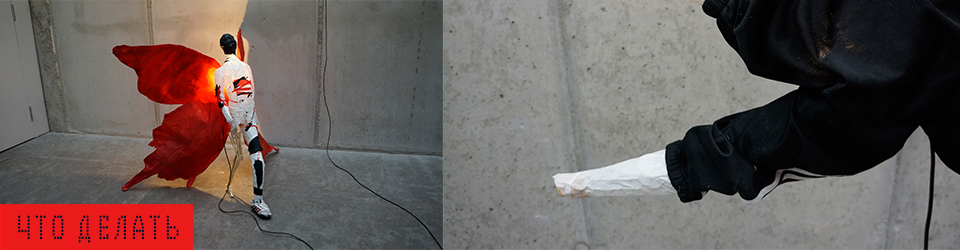

This brings me to the real crux of the matter: maybe solidarity is something that only become possible when we aren’t just expressing our sympathy, but when our “bodies” (to return to Buck-Moriss’ metaphor) revolt, when we empathize with those people who are appealing to us.

Perhaps it makes sense to think of politics as something beyond sympathy, as something based on an empathic experience that leads to the “existential” root of any genuine politicization. (The moment which the critic Dietrich Diedrichsen identifies when someone stands up and declares that “I can’t live like this anymore”, meaning “I can’t live knowing that the others live like this”, or “in fact, nobody should live like this, no matter whether they belong to our group or not”).

The question, then, is: can aesthetics be understood as a conduit for the kind of empathy that leads beyond the closed community of friends, beyond sympathy for some disconnected other, beyond performances that mean very little once these part of thespectacle is over?