Here we mention our long-term collaboration partners and good friends – very sorry if we missed anyone

our works are represented by KOW Berlin

Russia

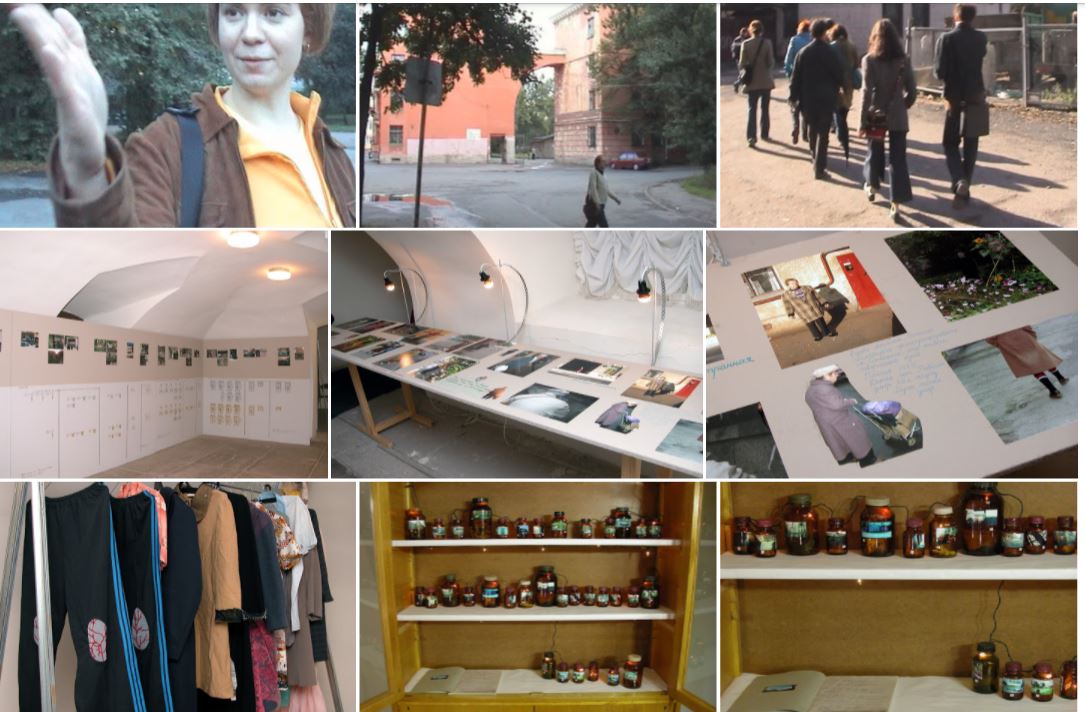

> Street Univercity, St. Petersburg

https://streetuniver.narod.ru/index_e.htm

> MoscowArtMagazine ///Московский Художественный Журнал

http://xz.gif.ru/

> Russian Socialist Movement/ Российское Социалистическое Движение

http://socialists.su/

> DSPA /// Движение Сопротивления имени Петра Алексеева

http://dspa.info/

> May congress of creative workers /// Первомайскийконгресстворческихработников

https://may-congress.ru

> Collective Action Institute //ИнститутКоллективныхДействий

www.ikd.ru

> FreeMarxistPublishingHouse /// Свободное Марксистское Издательство (С.М.И.)

https://fmbooks.wordpress.com/

> Translit /// Альманах актуальной поэзии и теории “Транслит”

https://trans-lit.info/

> Галерея Экспериментального Звука (Experimental Sound Gallery)

https://www.gez21.ru/

> Европейский универиситет Спб/ European Univercity Saint Petersburg

https://www.eu.spb.ru/

Kiev

> Р.Е.П. / R.E.P. Revolutionary Experimental Space

https://www.rep.tinka.cc/

> Visual Culture Research Center https://vcrc.ukma.kiev.ua/en/

Berlin

> Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung

> KOW Gallery

> Rosa Perutz is a self-organised discussion context, dealing with nationalism, statism, and the specific conditions of production and reproduction in contemporary art

https://perutz.copyriot.com/

> NGBK (Neue Gesselschaft fuer Bildende Kunst)

https://ngbk.de

> Interflugs ist eine selbstverwaltete und von Studierenden geleitete Organisation an der Universität der Künste Berlin www.interflugs.de

> Ex- Argentina & Potosi Principle net-work

(Alice Creischer and Andreas Siekmann) https://www.exargentina.org/

https://potosiprincipleprocess.wordpress.com/

– Hito Steyerl, Simon Sheikh, Boris Buden, Kathrin Becker, Kesrtin Stakemeier

Belgrade

> Biro for Culture and Communication (Vladan Jeremic and Rena Raedle)

https://birobeograd.info/

> Prelom Collective & Jelena Vesic

https://www.prelomkolektiv.org

> TkH is a Belgrade based independent platform for performing arts theory and practice

https://www.tkh-generator.net

> KUDA centar za nove medije, Novi Sad (Serbia)

https://kuda.org/

Buenos Aires

> Etcetera… formed in 1997 in Buenos Aires the group is composed of visual artists, poets, puppeteers and actors, most of who were under 20 at that time. They all shared the intention of bringing art to the site of immediate social conflict -the streets- and of bringing this conflict into arenas of cultural production, including the media and art institutions. https://www.facebook.com/?ref=home#!/grupoetcetera

> Collectivo Situationes; Federico Geller; Eduardo Molinari

Kopenhagen

> ex. Free University (Jakob Jakobsen)

https://www.copenhagenfreeuniversity.dk/

> The Learning Site focuses on the local conditions in which its art practice is located. This entails a critical examination of the material resources and economies available within specific situations. Each situation may entail examination of economic and environmental factors, but also labor rights, property rights and the production and distribution of knowledge, which are investigated in tandem to produce a variety of different critical perspectives.

https://www.learningsite.info/

Finnland

> Perpetuum Mobilε, co-founded by Ivor Stodolsky and Marita Muukkonen, is a conduit and engine to bring together art, practice and enquiry. It acts as a vehicle to re-imagine certain basic historical, institutional as well as theoretical paradigms in these fields, which often exist in disparate institutional and political frames and territories. Perpetuum Mobilεzations include projects such as RE-ALIGNED (www.Re-Aligned.net), the Perpetual Romani-Gypsy Pavilion (www.PerpetualPavilion.org), The Arts Assembly (www.TheArtsAssembly.org) and Perpetuum Labs.

Graz

> Rotor https://rotor.mur.at

Israel

> The Israeli Center for Digital Art in Holon

https://www.digitalartlab.org.il/Index.asp

> Anarchists Against The Wall

https://www.awalls.org/

The Netherlands

> Artist at Occupy Amsterdam network

https://www.facebook.com/?ref=home#!/groups/155194434576968/

> BAK, Utrecht

https://www.bak-utrecht.nl/?go=0

> Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

https://www.vanabbemuseum.nl/

– Charles Eshe;Merijn Oudenampsen; Jimini Hignett; Matthijs de Bruijne; Thomas Peutz & Una Henry

Spain

> Universidad Nomada& Marcelo Exposito

www/universidadnomada.net/

London

> Mute Magazine – Culture and politics after the net

https://www.metamute.org/content/magazine

>Third Textis an international scholarly journal providing critical perspectives on art and visual culture. It examines the theoretical and historical ground by which the West legitimises its position as the ultimate arbiter of what is significant within this field.

https://www.thirdtext.com/

> Precarious Workers Brigade are a UK-based growing group of precarious workers in culture & education. We call out in solidarity with all those struggling to make a living in this climate of instability and enforced austerity.

https://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com/

> Historical Materialism is a Marxist journal, appearing four times a year, based in London. Founded in 1997, it asserts that, notwithstanding the variety of its practical and theoretical articulations, Marxism constitutes the most fertile conceptual framework for analysing social phenomena, with an eye to their overhaul. In our selection of materials, we do not favour any one tendency, tradition or variant. https://www.historicalmaterialism.org

> no.w.here is a not for profit artist run organization based in Tower Hamlets

https://www.no-w-here.org.uk

– Steve Edwards, Gail Day, John Roberts, Susan Kelly

Ljubliana

> REARTIKULACIJA is an art project of the group Reartikulacija (Marina Gržinić, Staš Kleindienst, Sebastjan Leban and Tanja Passoni). It is based on a precise intervention logic; through contemporary political theory, critic, art projects, activism and self-organization, it aims to intervene in the Slovene, Balkan and international space. The platform allows networking with other political subjects, activists, artists, who are interested in the possibility to create and maintain a dialogue with concrete social and political spaces in Slovenia, Europe and worldwide.

https://www.reartikulacija.org/?page_id=2

> Radical Education Collective

https://radical.temp.si/history/

Bojana Pishkur, Marina Grzinic, Zdenka Badovinac, Vadim Fishkin, Mladen Dolar, Slavoj Zizek

Milano

> Disobedience Archive is an ongoing, multi-phase project curated by Marco Scotini and produced and presented by PLAY platform for Film & Video. The first phase started in Berlin in January 2005 and after Prague the next step will be in Mexico City in September 2005. Disobedience is a video station and a platform of discussion dealing with the relationship between artistic practices and political action. https://www.disobediencearchive.com/

Sao Paolo

> The BijaRi is a visual arts and multimedia breeding center. Developing projects in various platforms, the group operates between analog and digital media offering artistic experimentations, especially of a critical nature. Urban interventions, performances, installations, video art and design become a means to engage people, generating impact that generates a questioning of the current reality.

https://www.bijari.com.br/?lang=en

Sydney

>Zanny Begg – artist and activist web site

https://www.zannybegg.com

US

> 16 Beaver is the address of a space initiated/run by artists to create and maintain an ongoing platform for the presentation, production, and discussion of a variety of artistic/cultural/economic/political projects. It is the point of many departures/arrivals. https://www.16beavergroup.org/

> Greg Sholette web site

https://gregorysholette.com

> Artist Organisation

https://www.temporaryservices.org/

> Brian Holmes blog

https://brianholmes.wordpress.com/

> Creative Time

https://creativetime.org

> Tidal, occupy strategy journal

https://www.occupytheory.org/

Zagreb

Zagreb

> WHW (What, How and for Whom?) / Galerija Nova, curators collective

https://www.facebook.com/?ref=home#!/groups/70785898206/

> Theater collective Bad.co

https://badco.hr/

> FRAKCIJA, a Performing Arts Magazine

https://www.cdu.hr/frakcija/

International networks

> eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies and multilingual web journal

https://eipcp.net/transversal

> Former West a long-term international research, education, publishing, and exhibition project (2008–2014), which from within the field of contemporary art and theory: (1) reflects upon the changes introduced to the world (and thus to the so-called West) by the political, cultural, artistic, and economic events of 1989; (2) engages in rethinking the global histories of the last two decades in dialogue with post-communist and postcolonial thought; and (3) speculates about a “post-bloc” future that recognizes differences yet evolves through the political imperative of equality and the notion of “one world.”

https://www.formerwest.org/About

> ArtLeaks is collective platform initiated by an international group of artists, curators, art historians and intellectuals in response to the abuse of their professional integrity and the open infraction of their labor rights. In the art world, such abuses usually disappear, but some events bring them into sharp focus and therefore deserve public scrutiny. https://art-leaks.org/

> International Errorist movement

https://erroristkabaret.wordpress.com/

> Ultrared

Activist art has come to signify a particular emphasis on appropriated aesthetic forms whose political content does the work of both cultural analysis and cultural action. The art collaboration Ultra-red propose a political-aesthetic project that reverses this model. If we understand organizing as the formal practices that build relationships out of which people compose an analysis and strategic actions, how might art contribute to and challenge those very processes? How might those processes already constitute aesthetic forms?

https://www.ultrared.org

Outdated

Documenta_12_magazines – was very important!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Documenta_12_magazines