This issue of the newspaper “Chto delat?” is published in a framework of the Chto Delat film project “Partisan Songspiel” and with the support of 11th International Istanbul Biennial

editor and lay-out: Dmitry Vilensky /// graphic works: Natalya Pershina (Gluklya)

translations: (Russian – English): Thomas Campbell and David Riff

Sergei Zemlyanoi /// Bertold Brecht’s Project for Humanity

In 2003, I translated Brecht’s Me-ti. The Book of Changes into Russian. Me-ti is a slightly distorted name that belongs to the ancient Chinese philosopher and politician Mo-Dzi (Mo Di; 479-400 BCE), while The Book of Changes (I-Ching) is the name of a classical tractate written in the 8th to 7th century BCE, which was subsequently reused by many ancient Chinese thinkers.

Dmitry Vilensky /// Chto Delat and Method: Practicing Dialectic

Mixing Different Things

The editorial and exhibition policy of Chto Delat is often accused of inconsistency, of lacking a clear “party line.” What is important for us today is to arrive at a method that would enable us to mix quite different things—reactionary form and radical content, anarchic spontaneity and organizational discipline, hedonism and asceticism, etc.

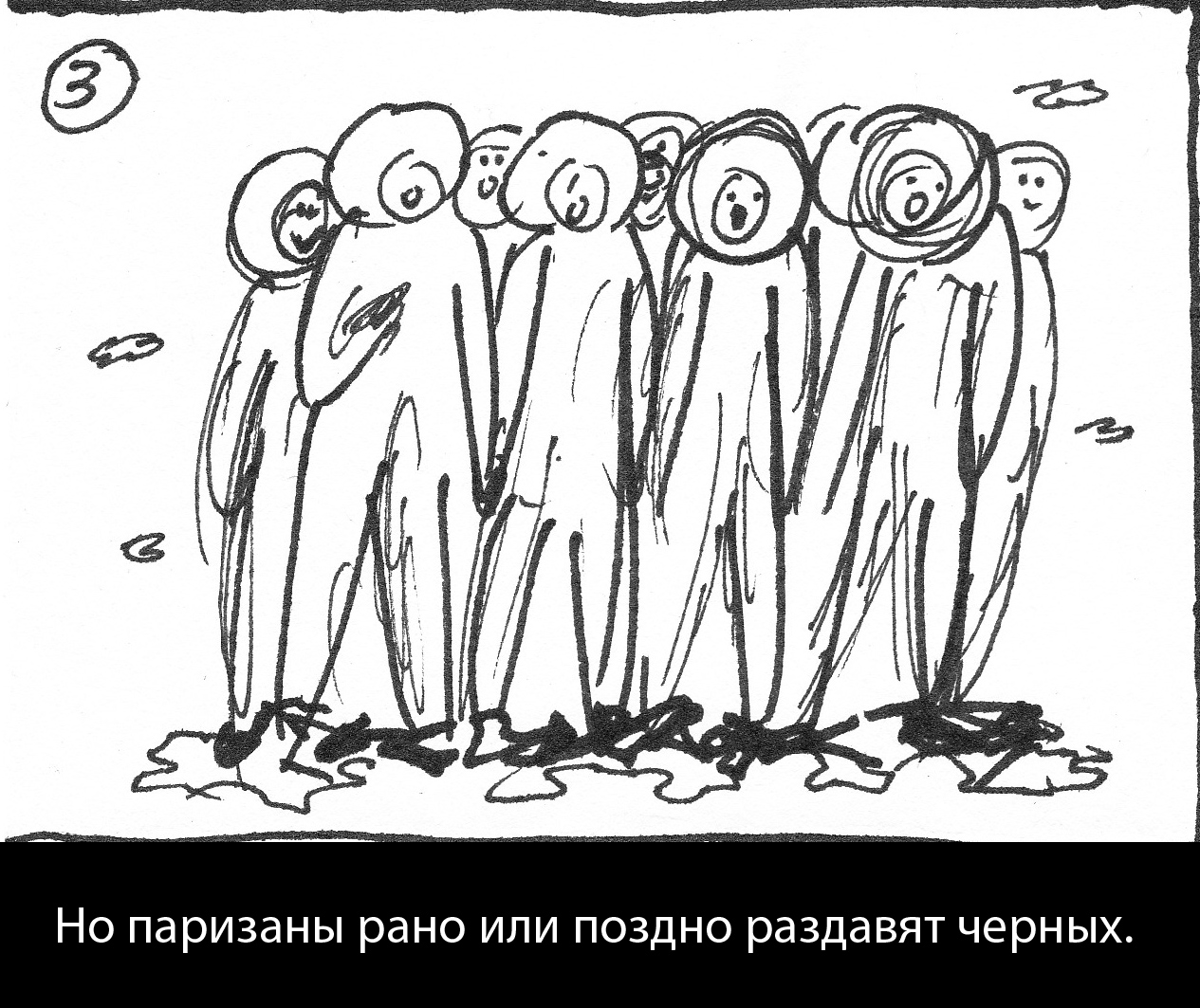

Partisan Songspiel: A Belgrade Story

Screenplay for a video film. Written by Vladan Jeremić, Rena Rädle, Tsaplya and Dmitry Vilensky. Introduction by Vladan Jeremić & Rena Rädle

Peio Aguirre /// From Method to Change: Dialectics in contemporary Art

1. The day Godard and Gorin set out to America to finish Tout va bien (1972), it seems the latter forgot his passport at home, while the former went to a bookstore to buy Bertolt Brecht’s Me-ti when Gorin warned him that they would have an accident. In the Rue de Rennes a bus hit Godard’s motorcycle leaving him and his companion (film editor Christine Aye) seriously injured. Godard spent several years in and out of hospitals. It could be called a “dialectical” accident, or the “logical end of 68”, or the last days of the Dziga Vertov Group. This affected the shooting of Tout va bien and months later, when they encountered Jane Fonda again, she had changed her state of mind to the point of “not working with men” and the film ended with no less difficulties.

Gene Ray /// Some Notes on Brecht and Dialectics

In the theater and forms of writing he practiced, Brecht tried in many ways to depict “the immense pressure of misery forcing the exploited to think.” In discovering the causes of their misery, they discover themselves, as changed, changing and changeable humanity. Seeing the world opened up to time and history in this way, Brecht was sure, inspires the exploited to think for themselves and fight back. Any art that shows this process becomes a weapon of class struggle. Brecht theorized this kind of committed art under different names at different times. “Realism” and “dialectics” are probably the most useful, and the most important to grasp. In the precise but flexible way he developed these terms, they may be helpful to those seeking to develop an effectively politicized artistic practice today.

Antonio Negri /// Some thoughts on the use of dialectics

1. Dialectics of antagonism

Anyone who took part in the discussions on the dialectics developed by so-called Western Marxism during the 1930s, 1950s and 1960s would easily recognise how the roles played in those debates by Lukàcs’ History and Class Consciousness and the work of the Frankfurt School were complementary. In a strange and ineffective hybridisation, a series of phenomenological descriptions and normative hypotheses produced in those periods regarded life, society and nature as equally invested by the productive power of capital and their potential as radically diminished by it. The question of alienation traversed the entire theoretical framework: the phenomenology of agency and historicity of existence were all seen as being completely absorbed by a capitalist design of exploitation and domination over life. The dialectic of Aufklaerung was accomplished by the demonization of technology and the subsumption of society under capital was definitive. The revolutionaries had nothing to do but wait for the event that reopened history; while the non-revolutionaries simply needed to adapt to their fate, Gelassenheit [1].

David Riff / Dmitry Gutov /// Simply Describing

David Riff: Do you remember when we visited Fred Jameson at Duke University a couple of years ago? On the first night in America, Fred’s assistant Colin took us to a burger bar, where we sat around drinking beers and making small talk. Colin was telling us about his research: Adornian music theory, post-operaist virtuosity, and American radical politics. Suddenly, there was this extraordinary moment. Our friend Vlad Sofronov, a very thin Trotskyist bald spectacled activist philosopher who had been silent all evening, leaned over and looked Colin straight in the eye. Head on, he asked him in a thick Russian accent: “Colin, what is your method? Simply describing?” I want to start our dialogue with a similar bluntness: what is your method, Comrade Gutov?

Dmitry Gutov: I remember the situation very well; it is etched into my mind. What did Vlad want to say with his question? That “simply describing” is not our method, that it is non-partisan positivism that suspends its judgement on the phenomena of reality and is therefore poorly suited to the revolutionary transformation of reality.

MORE ARTICLES…

- Алексей Пензин /// Диалектика и субъективность: вместо введения

- Оксана Тимофеева /// Диалог о методе

- Владислав Курочкин /// «Ме-Ти» и диалектика

- WHW /// What Keeps Mankind Alive?

- Геральд Рауниг /// Искусство и революция. Трансверсальный активизм в долгом двадцатом веке

- P. Aguirre /// Methodologies

- A. Badiou /// One divides into two

- F. Jameson /// Valences of the dialectic. Chapter one

- Interview with Paolo Virno /// The Dismeasure of Art

- New Literary History. What is an avant-garde