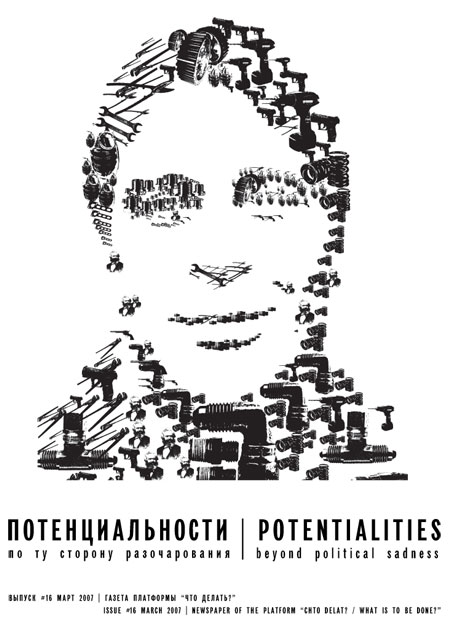

#16: Potentialities. Beyond Political Sadness

Artiom Magun – Alexander Skidan – Dmitry Vilesnky /// Potentialities

A Conversation about Possibilities, about Power and Powerlessness; about Labor, about Faithfulness to the Event; about the Realization of the (Post-)Soviet Experience; about Ascesis, the New Barbarism, and the Ecstasy of Consumption; about Bare Life and Superfluous People; and about How to Be Ahead of Oneself

Dmitry Vilensky: As we begin our conversation about potentialities, we need to make a precise link to our contemporary reality. We need to try and discover what potentialities are arising now, in a period that, in the last issue of this newspaper, we characterized as reactionary. As we found out when we talked with a number of people, both in Russia and elsewhere, most of our interlocutors are in a state of disenchantment; they spoke of their melancholy, of feeling disoriented. That is to say, many people who were full of hope not so long ago (when, as it seemed, a new set of possibilities opened up) now have a greater and greater sense of limits, of the impossibility of realizing their potential. An important personal experience for me was the failure to mobilize for the Petersburg counter summit: the opposition demonstrated its bankruptcy at all levels; the limitations of the movement became quite apparent. Of course everyone loses heart and says to himself, Well, whatever: I’ll mind my own business, worry about my career, make some money, take care of my family. One guy escapes into Buddhism, another into Russian Orthodoxy; some people retreat into everything all at once. Once again we see a boom of esoteric practices. Once again the question arises: if our ability to realize our desires and possibilities is more and more limited, then where are our potentialities formed-potentialities that, I persist in hoping, might be actualized by the course of history?

What, How & for Whom / WHW /// Magical world, these days

What options of personal and collective imagination are still open in a society whose “Shop till You Drop” consumerism philosophy gets strongest opponent in the Catholic Church and whose primary patterns of social behavior are patriarchal representations of national identities? Can there be a rift, a critical change in perception that will unearth complex relationships that that keep getting ignored, made unfashionable by their lack of “New Europe glamour” and non-marketability, swept under carpet or even openly suppressed, such as relationship to the past and construct of history, negative impact of economic transition, questions of national identity and nationalism, post-war normalization, pro-EU orientation and status of ethnic minorities (primarily Serbian) in contemporary Croatian society?

Katja Aglert & Janna Holmstedt /// To turn one’s anus towards the sun and say “GO”!

YELLOW MONDAY

Monday, in front of a cash machine at Siam Square in Bangkok. I wonder if it is a video module of some sort or if I am standing in front of a machine that actually will provide me with a financial service. On the screen there is a moving image of a smiling man, dressed in yellow and jewellery that I recognise as the Royal Highness of Thailand – the King. Why is he on this cash machine greeting me before I insert my VISA card?

A moment later: inside the enormous shopping centre in line for the toilet. I notice that a majority of the people here wear yellow t-shirts. The walls inside the rest room are made of thin frosted glass and the entire interior is exclusively designed in steel and stone. Large flat screens are inserted in the thin glass and they scream out a diversity of commercials for us in need.

Per Hasselberg and Frans Josef Petersson /// A dialogue between social minded indiviuals

Frans Josef Petersson: Two years ago you initiated Konsthall C in Hökarängen, a suburb south of Stockholm, as a part of your artistic practice. The project can be described as a reflection on a political model – the social democratic welfare state, the just society, the ‘Swedish model’ or whatever one may call it – as this was manifested in the planning and construction of Stockholm from the 30s onward. What does Konsthall C and Hökarängen signify for you, and what do you think about the model they represent?

Per Hasselberg: Hökarängen is an historical model for accommodating citizens in small-scale, neighbourhood units that was subsequently implemented in the Planning and construction of Stockholm and other cities around the country. The aim was to create social-minded individuals, with an active interest in common matters, with an ability for critical thinking and collaboration with other people to make possible the implementation of necessary social reforms. In short, to facilitate the growth of democratic citizens, for whom liberty and autonomy is combined with a sense of social responsibility, according to the architect and social democrat Uno Århén [1]. An important aspect of this was to integrate natural meeting places in the built environment*, and in Hökarängen a central laundry room was designed to also function as a local community centre. A place for people to perform their daily chores but also socialize with their neighbours. Konsthall C is situated in this very space, with only a glass wall dividing it from the still functioning laundry room.

Esther Leslie & Ben Watson /// What Now?

EL: Times New Roman / BW: Arial

Art/Futures

Managers of the culture system and private possessors of art pin their hopes on art’s futures. The beer brand Beck’s, for example, calls its art sponsorship programme Beck’s Futures. Financial software service company Bloomberg manage a programme called ARTfutures: For those in the market for cutting edge contemporary art, whether first-time buyers, or new or committed collectors, the Contemporary Art Society’s annual ARTfutures, is a “must see”‘, states the call to collectors in 2007. What is that future that art managers so confidently claim to dictate or discover? On the one hand a simply economic calculation. It signals to collectors buy here, buy now, for future return. Bloomberg tracks and predicts emerging markets as well as emerging artists. Beck’s is a brand worthy of investment, so too its hallowed artists. Of course, it cannot just be this and Beck’s Future’s, like all such projects, claims that the future it is interested in is the artist’s own, allowing its successful sponsees to develop their work. The future in art has a long tradition: it is an element of avant-garde production. Better-world-boosters – futurists, constructivists, productivists – conceived blueprints for the future. This did not mean that art re-presented tangible images of future worlds. Rather it instituted modes of non-commodified production – collaborative, or refusing single authorship in the bourgeois sense by subjection to the public statement of the manifesto. And they piloted transformed social relations by what Brecht called refunctioning’. As Benjamin wrote of Brecht’s practice in The Author as Producer’ (1934), refunctioning is the transformation of the forms and the instruments of production in the way desired by a progressive intelligentsia-that is, one interested in freeing the means of production and serving the class struggle’. In the case of the Soviet artists especially there was some justification for functional transformation of the forms of art in an effort to test run new social relations and skills. The Soviet avant garde operated in times of transformation, not least times of transformation for art, which emerged from the galleries and museums, dropped its preoccupation with individualistic artists, instead organising itself into agit-prop groupings, grasping towards new technological forms of expression, and rushing forward to meet its audience on newly defined terms.

Alexei Penzin /// No Time

Remembering a famous statement by Augustine, we might agree that is not easy to speak about what time is. But it is easy to speak about the fact that there is no time. One of the characteristic traits of the new quotidian of recent years can be found its special temporality. “I can’t, I don’t have time!” is something one hears quite often, not only among overworked business executives, but also in the various “creative industries,” in the arts, and even in academia. People of the older generation still remember a Soviet temporality that made it possible to dedicate years of unhurried reading to eccentric scholarly undertakings lacking any exterior goal. Against the backdrop of today’s time deficit, such memories sound like nostalgic legends.

The lack of time described above is hardly just a “natural” moment of our generation’s coming-of-age, nor is it simply a consequence of some trivial logic of survival in post-Soviet society. Talking to friends from other countries, you can see astounding correspondences in how they organize day and night. One sees a certain globalization of time: a multitude of parallel projects and texts that need to be written to meet this or that “deadline,” a multiplicity of virtual internet communications with various rhythms.

David Riff /// The Potentiality of Mimetic Labor

I recently came across a medical term called “mimetic labor,”which means a false start in pregnancy. Painful contractions begin, but the cervix does not dilate. Potentiality rises to a peak. The bubble seems about to burst into actuality. But it doesn’t happen. The contractions subside, and pregnancy continues. In English, labor means both the contractions of childbirth and reified work, so that there is a somewhat dodgy metaphorical link to what mimesis does and can do as a mode of actualization.

The late Soviet period produced a cultural fossil fuel that many people today want to actualize. Interestingly, the multiplicity of efforts in this direction articulates itself as a sequence of false starts, only projecting potential actualizations or threats of impending totality. But success or total change never comes, and the projection is abandoned in favour of another grander scheme. Each new ideological product has its own teleology. But it quickly becomes yet another addition to the encyclopaedia of fast moving consumer goods, thrown away too quickly to be used. Even projects that attempt to develop socialist strategies to engage the genuine emancipatory impulses of the Soviet past face this problem. Mimesis becomes a temporary magic, replaying all kinds of tragedies as an uncanny farce. Reality seems rife with a bad potentiality that cannot be represented, ready to burst at the seams precisely because meaning is being delayed. Reactionary times, we say, fraught with omens that interrupt the idyll. A little like the Biedermeier.

Colectivo situaciones /// Politicizing Sadness

More than five years after the insurrection of that Argentine December of 2001 we bear witness to the changing interpretations and moods around that event. For many of us sadness was the feeling that accompanied a phase of this winding becoming. This text rescues a moment in the elaboration of “that sadness” in order to go beyond the notions of “victory and defeat” that belong to that earlier cycle of politicization which centered on taking state power, and, at the same time, in order to share a procedure that has allowed us to “make public” an intimate feeling of people and groups.

Sadness arrived after the event: the political fiesta-of languages, images, and movements-was followed by a reactive, dispersive dynamic. And, along with it, there arrived what was later experienced as a reduction of the capacities of openness and innovation that the event brought into play. The experience of social invention (which always also implies the invention of time) was followed by a moment of normalization and the declaration of “end of the fiesta.” According to Spinoza, sadness consists in being separated from our powers (potencias). Among us political sadness often took the form of impotence and melancholy in the face of the growing distance between that social experiment and the political imagination capable of carrying it out.

Kerstin Stakemeier & Nina Koeller /// Not forgiving – Not forgetting – Space for Actualisation

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” [William Faulkner]

We decided to be not so interested in a number of things: in art in general, for a start, in art history as a discrete discipline, and in culture, as art’s more cheerful other. Instead, we are much more interested in artistic productions as significant documents of their historical setting, in art history’s cutting out the political revolution from revolutionary artistic productions and in culture as a momentous subdivision of general production.

In the ”Space for Actualisation” we are attempting to work on another form of cut-out, one which plays out possibilities against realities, which measures its cuttings by the hopes it has for the present and which takes the past not for what it was, but for what it could be: An Actualisation is a cut-out from the past, pulled into the present to actualise its potentials and to supersede its own role in a history, whose revolutionary phases were much too short-lived and rare.

Hito Steyerl /// The Presence of the Subaltern

Is today’s working class subaltern? Or, to paraphrase the title of Gayatri Spivak’s notorious text: “can the working class speak?” At first glance, this question is shocking. At second glance, it seems misplaced. Can one really say that the working class faces the kind of radical exclusion from social representation that the notion of subalternity suggests? In the light of the worldwide spread of social democracy, and its countless trade unions and labor organizations, the question sounds paradoxical and even somewhat crazy. What does it mean to claim that today’s working class is silent?

Cut to a different scene. “Tout va bien,” a film by Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin from 1972, shows an interview with a worker in an occupied sausage factory. Jane Fonda plays an engaged reporter who has sympathy for the female workers there and wants to confront the public with the conditions of their lives. The interview, however, is presented in an unusual form: we see the interview taking place, but hear a voiceover of another worker’s inner speech as she observes from the sidelines, thinking that the interview will present the public with a yet another set of stereotypes, and indicating that social reporting is just a cliché, an excuse for keep ignoring the workers as “victims.” Godard and Gorin make it abundantly clear: no matter how hard the Jane Fonda character tries to amplify the female worker’s voices, she will never succeed. She is up against the cumulative force of discursive clichés. The more she wants to let the workers have their say, the louder their silence becomes.

Katya Sander /// [no title]

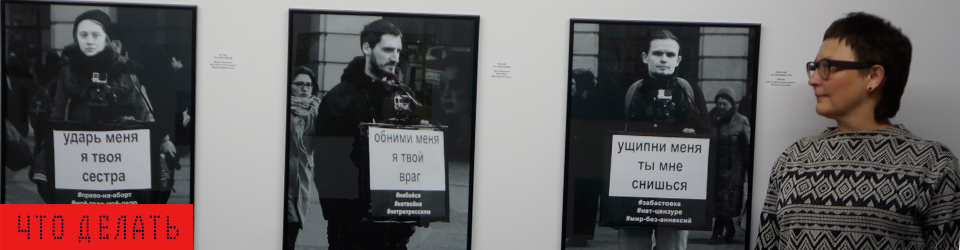

The image of an activist, a protester, a demonstrator…

Some years ago I worked on a film, “Exterior City”, in which I wanted to investigate some thoughts and images about urban planning in the light of social democracy and its history of turning ‘masses’ – a idea of a disorderly, disruptive and chaotic force of bodies – into ‘a people’, implying an orderly collective entity with direction and name. Part of my investigation was carried by my curiousity for how this production of ‘people’ (or ‘citizens’) was in many ways contingent on organization of an address and articulation of a demand.