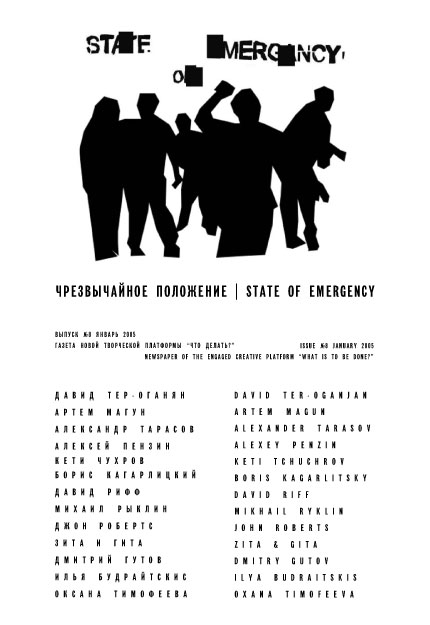

#8: State of Emergency

Workgroup “What is to be done?” /// Editorial

Definitions of historical concepts: Catastropheto have missed the opportunity. Critical momentthe status quo threatens to be preserved. Progressthe first revolutionary measure taken.

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project , trans. Howard Eiland, Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 474

Not so long ago, the “state of emergency” still sounded like an abstract juridical notion and seemed reminiscent of the last century’s fascist regimes. Yet today, as the result of recent catastrophic changes in the situation, the “state of emergency” is in the process of becoming a quotidian reality, a strange new “norm” that affects all areas of life, a grey backdrop of the everyday. New systems of surveillance are implemented; public space is privatized and placed under strict control; censorship dams the flow of information; passport-controls and travel-restrictions limit freedom of movement; suspicious individuals are searched and detained; elections are falsified, all in the name of the battle for democracy and human rights. But while the governments of the past fought such battles by declaring states of emergency, today’s suspension of the law no longer requires any name: the law’s zone of blindness is spreading unseen.

Artem Magun /// Emergency excepting Emergency

“The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule. We must attain to a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight. Then we shall clearly realize that it is our task to bring about a real state of emergency, and this will improve our position in the struggle against Fascism.”

Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History, Walter Benjamin, »Über den Begriff der Geschichte«, in : Illuminationen, Frankfurt a. M. 1977, p. 254. (»On the Concept of History«,https://www.tasc.ac.uk/depart/media/staff/ls/WBenjamin/CONCEPT2.html)

This fragment of the 8th thesis of Benjamin’s politico-philosophical manifesto On the Concept of History doesn’t say anything that would be too complex. Benjamin demonstrates that the exaggeration of the emergency that comes from the fascism coexists nicely with the liberal faith in the constant progress towards the better. Talk of emergency complements this faith. If we believe that everything, in principle, is getting better and better, then any crisis or conflict will appear as extraordinary, scandalous to us. We are like the angel of history (a critical, ironic concept, contrary to popular opinion) who flies progressively forward, but who looks at the present from the point of view of a better future, thus perceiving the present as a pile of ruins. Fascism plays on this situation by turning trauma into value, by joyfully imposing the state of emergency and by making it a regular state of affairs. But emergency in the fascist sense is not truly exceptional, precisely because it is also regular (i.e. contaminated with liberalism), and thus neither exceptional nor regular.

A. Tarasov, O Timofeeva, A. Penzin /// The State of Emergency We Need To Get Rid Of

We still have yet to understand that the emergency laws are a general offensive aimed at political democracy, led by the bosses of capitalist society; a general offensive of the rulers against the ruled; a general offensive of the ruling class against all of those who do not want to become part of the system of total consumption… What the bosses want now is nothing less than a parliamentary ratification of their policies, a confirmation of their growing power… Our goal lies in the democratization of both state and society. The struggle against the emergency laws are but one of the means of achieving this goal, one of the means of overcoming the dictatorship of capital over state and society. But we will never be able to achieve this goal if all we do is continue to resist being transfered from a large prison cell into a smaller one, forgetting that the only real liberation from prison is escape.

Ulrike Meinhof, “Notstand-Klassenkampf”

Alexei Penzin (AP): In formulating the theme for our discussion, we departed from obvious social and political things. An atmosphere of a so-called “threat of terror” is being drawn up all around us. The state acts as if it were already in a state of emergency, without ever declaring it officially. It suspends the operation of constitutional principals and introduces special regimes of surveillance and control (e.g. the passport-regime in Moscow ). Russia ‘s constitution actually contains a law of the state of emergency, as do many other constitutions. But our legislature has added a regime of “counter-terrorist operations” to this law, and is currently attempting to add yet another juridical regime, a law on the “threat of terror”. In other words, we live under the conditions of a deferred state of emergency , under which the government multiplies the corpus of juridical rules for emergency while intensifying its rhetoric of threat. It seems that a “real” state of emergency is about to be declared, but this never really happens. Either the government is incapable of implementing this state in reality, or it is simply playing a propagandistic game, constantly flirting with foul play. In preparing this issue, we were inspired by a fragment by Walter Benjamin, which says that we need to supply the “state of emergency” with a broader philosophical and critical meaning. The state of emergency (Ausnahmezustand) is inscribed into history’s very progression, uncovering theontological emergency or exception of class-society itself. How would you assess the attempts undertaken by a number of contemporary thinkers, such as Agamben, for an example, to turn the “state of emergency” into a notion capable of offering a diagnosis for our contemporary condition?

Alexei Penzin /// Ukraine: Revolution Under Construction

It is more pleasant and useful to go through the “experience of revolution” than to write about it ..

V.I. Lenin (“The State and Revolution”)

The narrative of the current debates on the nature of the “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine explicitly or implicitly is defined by the notion of the difference between revolution and its imitative construction . It is this difference that generates all of the further ideological combinations of position. In the structural turn of events that concerns us here, it is not yet important what characterized this revolution, if indeed it was a revolution. Instead, the main question is whether we can record the event of revolution at all, whether this event had its place. If so, the events in Kiev cannot be reduced completely to media-propagandistic contexts and manipulations, following the contemporary philosophical notion of the autonomous event, which is not pre-determined in terms of significance. This argument can be approached in a dialectic mode, a mode which does not seem to be theoretical “retro” in this case, since it allows us to actualize the line of thinking on revolution that began as early as the 19th century.

Keti Chukhrov /// Nothing to Discover?

The changes that have been taking place in Russia for the last five years can be called exceptional to the point of emergency. These changes express themselves in a completely new rhetoric of power, which, in contrast to previous systems, has succeeded in constructing its ideology through the complete ambivalence of political priorities.

Under these conditions of the full indeterminateness of any ideological choice, the state has only succeeded in creating a simulatory “patriotic field”, which accumulates all of the traumatic symptoms of previous regimes: sovereign monarchism, Russian-Orthodoxy, Communism, the war in Chechnya etc. It has also been successful in combining contradictory types of PR: xenophobia and the struggle against it, “friendship” with the West and an undeclared war led to regain the positions lost during the post-Perestroika period, the declaration of net surplus and the refusal to make social investments.

David Riff /// Where is the Hope in this Dialectic?

In Russia , the last three years have been a period of artificial economic and political consolidation over the representative sphere. The New Russia needs to look more respectable, modern, and fashionable; never mind the nationalism and the criminal past. The main thing is to look good for the global marketplace, to play at “law and order”, and to render all of the very real social problem-zones invisible. During the last 6 months, the struggle for the means of producing visibility has been undergoing a paranoid radicalization. Highly visible politicians announce extraordinary measures and make frightening promises, all of which concern the visible future : “You won’t recognize this country in a couple of years.” It is important to realize that this shift in representational politics does not only apply to governmental strategies, but affects all areas of cultural production. For an instance, the new Russian elite requires a new means of representing its legitimacy, one of which is possibly contemporary art. The need for representative unity justifies the temporary implementation of extraordinary measures, a purge, not only to stimulate society’s atrophied tissue, but to declare sovereignty over the field of visual production, to coerce an extremely fragmented milieu into consolidation. What is needed is a biennale .

Boris Kargalitsky /// Open Letter on the Moscow Biennale

The First Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art has chosen “The Dialectics of Hope” as its theme, which, incidentally, is the title of a book I wrote in 1980. Naturally, I have no exclusive claim to the word “hope”, nor to the word “dialectics”, for that matter, nor to their combination. However, the organizers of the Biennale have never hidden the fact that the name of the project has been connected to my book from the very beginning; what’s more, they have made several public announcements to this effect. Thus, I feel that I have the right and even the duty to make a few remarks on the processes that are taking place around the Biennale.

Seeta and Geeta /// Forget

Dis-order-time is over. New order is a steady state. It’s everywhere. The masses want order. The masses are asking for it. For seventeen years, there was all these institutes. They coexisted. Some: old Soviet offices with new furniture. Others: new. New and improved, they got lots of money-mind aid from the West. But now, they’re strict; they’re cutting those structures and influence-zones.

What’s important for art: that new order doesn’t need no old order repetition, no reload of crazygrand total narratives. It’s OK to diss from the fringe of the industry. If you got some critical position on the oligarchs, the war, the state, or the total dominance of liberal oligarchy, ain’t no one gonna move you. But your position is always an item of cost. No money, no love: pay your way. Your place: an industry-item in some cigar-smoking motherfucker’s product-range. The cynicism of the art-situation: unnoticed participation in capital-turnover, unseen in the world’s repartition through economic recondition.

Mikhail Ryklin /// The New Science of Pogromology

On January 14th, 2003 , the exhibition “Careful, Religion!” was opened in the exhibition hall of the A.D. Sakharov Center in Moscow . Curated by Arutyun Zulumyan, the exhibition showed the works of 39 artists and two artist groups; the show did not only include artists from Moscow , but from Armenia , the USA , Japan , Bulgaria , Czech Republic etc.

After four days, the exhibition was wrecked by six men claiming to be Russian Orthodox believers, who said they felt that the majority of the works shown at the exhibition were a mockery of their faith. Some of the art works were sprayed with paint from a spray-gun, others were torn from the walls and thrown onto the floor, and others yet were smashed to pieces. The museum guard was able to call the militia in time, so that the perpetrators of the pogrom were arrested, charged with vandalism, and released on bail.

In August 2003, the people who had wrecked the exhibition were vindicated in court. However, at the demand of the Duma, the state-attorney opened a criminal investigation of the exhibition’s organizers on the charges of “fomenting national and religious discord”. In the context of this investigation, the attorney ordered an expert-opinion of the art works shown.

Ilya Budraitskis /// Man and Bomb. Notes on the Work of David Ter-Oganyan

“Our consciousness arises wherever we feel life’s dissonances and their signals, since our consciousness calls the elimination of such disharmony”, wrote the Marxist critic Alexander Voronsky in the 1920s. According to this definition of art’s cognitive role with regard to society, the creative act pursues the primarz goal of destroying the oppressive monopoly of commonly accepted rules for the restoration of relative harmony between the milieu and ourselves. Life in today’s world cannot help but provoke the bravest possible methods to restore the lost balance of the author’s aesthetic feeling.

There are only a few seconds left before a small explosion. Just a flash and the nasty smell of organic gases fills the room. These are fart-bombs, little stinkers, toys that you can buy in any shop that sells novelties or practical jokes. The fart-bombs’ owner is faced with one central, definitive choice, namely the right to choose a space. Be it a smoky art-café, a darkened movie-theater or a pathos-laden round table of the “expert community” of intellectual prostitutes, any space is good enough to create a new situation, to supply all of this idiotic and irritating reality with a new, subtle and critical dimension. The smell of the little stinker is capable of generating the most unexpected readings of public spaces that would have seemed to be terminally occupied. Decisively demanding their own removal, these stink-bombs are capable of radically democratizing any authorial social event, presenting any owner with the unique opportunity to play his own, unobvious game.

Oxana Timofeeva /// Suspicious Faces

In the passages and on the escalators of the Metro, I hear a familiar call echoing out of no-where: “Pay attention to suspicious persons”, (i.e. homeless people, drunks, smokers and beggars), “and to ownerless objects.” Mortal danger rings its signal through the the tunnels of the underground: “people in dirty clothes” sully its cars and benches like a plague; objects that are nobody’s property send it flying into a rage; cigarettes could cause a fire, and somebody’s alcoholic breath against the nape of somebody else’s neck is enough to incur its frenzy. I hear that signal up to ten times a day; I remember it by heart, often enough to make me suspicious: something is wrong here. It’s as if the city that I’m travelling under were suddenly nothing but a paranoid figment of some lobomized brain. As if this wasn’t our world. As if this world were alien.

Dmitri Gutov /// Excess

The story of King Wei, who lived in China during the 4th century, tells us that the ruler’s greatest pleasure was to observe the dance of the cranes. The movements of this bird were a paragon of unpretensious looseness of poise; in a broader sense, they were a constant reminder that one should never renounce one’s freedom under the pressure of circumstance.

Yet the king paid dearly for his love of cranes. One day, he looked at one of them for too long while a battle was taking place, which he lost. The strength of his aesthetic experience was defrayed by his loss of command. Among China’s men of letters, this fable became the object of discussion for centuries to come. Some scorned Wei, while others marvelled at his composure. Both one and the other interpretation of his conduct laid the foundations for entire schools of thought.

John Roberts /// Internationalism and Globalism

Vladimir Putin’s demand for ‘controlled democracy’ represents an attempt to bring the uncontrolled period of prikhvatizatsia – or ‘wild’ market implentations – under greater state control, hence the President’s recent much-publicized confrontation with the so-called oligarchy and mafia. But the shifting sands of privatizatsia means Putin’s controlled democracy is less an assurance of stability than something faintly sinister. Controlled democracy has become the watchword for the recentralization of the state in conditions of faltering economic growth. The majority of the Russian population is unable to participate in privatizatsia, because they are living below the level of subsistence and therefore are incapable of paying the true cost of commodities. In the area of housing, for instance, tens of thousands of new apartments in St.Petersburg remain unsold. Something like 5% of the population has Western levels of consumption. Thus if Putin has put the break on bandit capitalism’ he has also to contend with growing social unrest and frustration. Most Russian enterprises cannot compete on world markets; and labour, although cheaper than the West, is more expensive than China and the Third World. This will produce increasing conflict over resources in the near future, and conflict over the cost of Western’ privatizatsia. For ideologically and practically privatizatsia is not a done thing in Russia, by any means. Indeed there is a residual resistance to its effects after the first period of de-Stalinization. This has much to do with the continuing impact of collectivist thinking in everyday life and within what is left of state provision in the area of housing. In fact the state bureaucracy, at the moment, plays a paradoxically progressive role of preventing a thoroughgoing implementation of privatizatsia. A residual collective ideology has increasingly come to define – in the absence of the labour traditions of bourgeois social democracy – what is not acceptable about privatizatsia.