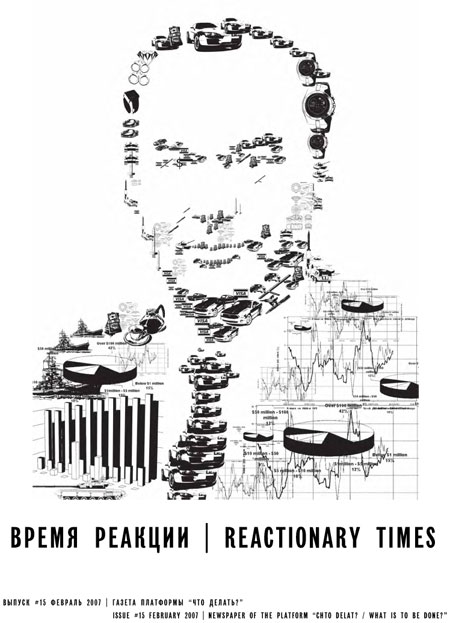

#15: Reactionary Times

Dmitry Vilensky /// The Capitalization of Beliefs

In the ‘strength of negativity,’ Hegel saw the vitality of the spirit, and, consequently, of reason. In the final analysis, this strength was the strength to grasp and change given facts in correspondence with the development of potentialities, and through the negation of the ‘positive’ as soon as it became an obstacle blocking the path of free development. At its very essence, reason is contradiction, opposition, and negation until freedom does not become a reality. If the contradictory, antagonistic negative force of reason suffers a defeat, reality moves in accordance with its own positive laws; meeting no resistance from the side of reason, it unfolds its own repressive force.

Herbert Marcuse, from ‘Reason and Revolution’

I’m not exercising censorship but face control. You have to know what times we’re living in.

Oleg Kulik on his curatorial role in the project I BELIEVE

01.

Russia. Early 2007

Recently, there has been a flood of propaganda to convince us that life is getting better and that all the miseries of the transitional period are a thing of the past. Ours is a time of stability and normalization. The quality of life is improving. Wise leaders rule the country, enjoying the populations blind trust. There are no alternatives to the road ahead. Recent legislation makes it easy to declare that anyone who voices any serious doubts as an extremist, an inner enemy, or an agent of one of the growing number of adversaries abroad. In the media, there are more and more stereotypes convincingly reminiscent of Brezhnev-era phraseology. Feverishly scouring bygone epochs for sources of legitimacy, power chooses those moments that epitomize stagnation, stubbornly repressing their eventual outcome from collective memory.

Igor Chubarov /// Notes on Faith, or, Oleg Kulik’s Jacuzzi

Therefore, what we are lacking (for we do lack something in particularthere is no point in hiding that it is politics we lack) is not at all the matter and the forms from which myth might be fabricated. For that there is always sufficient rubbish, ideological kitsch that is as banal as it dangerous. What we lack, however, is the insight necessary to discern the events in which our future truly has its origins. They are not, of course, produced in the return of myths. We longer dwell in that dimension, in the logic of the source. We exist belatedly, in a historical future perfect. Which does not rule out the fact that the limit of belatedness might prove to be the starting point of some innovation. Moreover, it is precisely this that demands our thought.

– Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy, Le mythe nazi

Many visitors to the pretentiously titled I Believe! (which opened on the eve of the Second Moscow Biennale) share the opinion that the show is no different from any other group exhibition of contemporary Russian art. Even critics previously hostile to the show and several participants agree with this assessment. They differ, perhaps, only in what they choose to emphasize.

Viktor Misiano – David Riff /// Suspending Criticism: Criticism in Suspense

David Riff: In the last three or four years, Moscow’s contemporary art scene has undergone some intense development, bringing new galleries, foundations, institutions, and big events. The homogenization of the public sphere has heralded processes of consolidation that go in hand in hand with an influx of capital in search of representative cultural investments. A gentrification that has been approaching Moscow for the last 10 years is now in full swing. It often seems like there is no escaping this process’ entrepreneurial logic and its pervasively glossy results. But when people try to come to terms with the new situation, they find themselves resorting to blanket notions: it is chalked up to the “market,” a figure of speech that is just as homogeneous as the “power” Russian liberals used to lament. Which realistic view could help us avoid conceiving of the new culture industry as a new version of the same old “bad totality”?

Viktor Misiano (VM): The institutional scene in Moscow really has changed over the last years. Still, let’s not exaggerate the scale of these changes, and most importantly, let’s note that they are not qualitative and contain no symptomatique that could be considered fundamentally new. Instead, it’s all essentially a realization of the model of cultural development suggested by the apologists of neo-liberal reform in the early 1990s. In Spain, for example, post-Franco reformers placed their bets on the development of a public infrastructure. In Russia, on the contrary, the focus has always been on dismantling the public sphere: the emergence of a private infrastructure, dominated by the principles of market economy seemed to promise the best perspectives for the future. In the official ideology of those years, the “market” was just as total a category as “power,” appearing as a universal solution to all the problems at hand. In fact, most new initiatives today are personal and private. Even those initiatives started up by the state profess the same ideology. This does not create a stationary, transparent infrastructure under community control, but “investment projects,” carried out by bureaucrat-businesspeople operating with money from the state budget.

Brian Holmes /// Beyond the Global 1000

In December of 2005 in the city of Sao Paulo, at the annual conference of the International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art (CIMAM), a German critic named Walter Grasskamp challenged the twentieth-century claim that the museum can be the institutional frame of a universal aesthetic language. He pointed instead to the globalisation of an essentially Western set of cultural codes, including the all-absorbing code of exoticism – a cannibalistic aesthetic whereby any sort of curiosity is admired because it is different. For Grasskamp, the art museum is comparable to the Wunderkammer, or curiosity cabinet. According to him, it’s very small – what you see all across the world, at the basis of modern art museums, are the same 100 artists. The rest are just curiosities.

The philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato spoke at the same event. He posits the museum as support base and relay point for an engagement with the outside – particularly with the massive technical infrastructures of globalization. The artist Ursula Biemann represented one of those infrastructures: the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline, whose construction she documented in a video called Black Sea Files. And the psychoanalyst Suely Rolnik further suggested that artistic experiments can transform even the basic universalising structure of the Western ego, which negates the Other.

Artiom Magun /// Three Passenger-Driver Dialogues

Trip 1. Chkalovskaya Metro Station – Airport

Driver: How much time is there?

Passenger: The question is not how much time there is, but what kind of time it is! We have plenty of time, but all of it is the time of reaction. Look: here in Russia, they are breaking up demonstrations, putting people into prison without due process, and creating loyal oppositional political parties. A small group of people is capable of pushing through any decision it likes. And most of our fellow citizens don’t contest this: they have no time to react! They go to malls, repair their apartments, and discuss their purchases on their mobile phones. People don’t regret their enclosure in private life: in this private life, they satisfy desires shared by others, desires that are advocated in reality shows, TV series and blockbusters! And even to criticize your government makes more sense if you use a mobile phone… But if these fellow citizens actually start thinking about something serious, they will be immediately given some religion or some occult bullshit substitute.

Driver: Yes, our people have gotten worse. It wasn’t like this before. There used to be collectivism; people smiled at one another, and helped one another. But now, it is the time of the wolves. And, as a Russian proverb goes, if you live with wolves, you howl with wolves.

Passenger: Yes, but we don’t have to be like them!

Luchezar Boyadjiev /// Who are the Good Guys?

I have been living in the EU for a month now… It’s not what I expected it to be… I mean, you only need to look at the holes on the roads they have all over there! Just the other day I drove somebody off to Sofia Airport – my God, what a dreadful ride! And they say EU is an elite club…, elite my ass, I say!

At least the government of this country, not that I voted for them mind you, has already started the procedure for Bulgaria to join the Euro zone as soon as possible, like in 2-3 years. That’s good I tell you, for they will finally get off our backs. They will have to recognize our home-made money; all those Euro bills that we are traditionally printing here in the country will no longer be treated as forgery!

I am not so sure about salaries though… The other day somebody published the findings of an economical forecast research saying that the average pay in Bulgaria will reach EU standards by the year 2230… In fact I should not be worried at all, in fact – that’s not my problem at all. Actually, things changed for me overnight in this department, which is great! You see, until January 1st 2007 I never made a single penny as an artist in my own country! I always provided for my family and myself by commuting to work in places West, South, North and sometimes East of the borders of Bulgaria, everywhere else but… So, now that my home country is in fact the whole European Union I can safely say that most of the work I do and most of the money I earn for the work that I do, I earn at home. And that’s a big relief, I tell you!

Ilya Budraitskis /// Opacity

The kaleidoscope must be smashed.Walter Benjamin, “Central Park”

The political in art does not consist of the degree of engagement in its form, but in the basic quality of the artist’s perception of reality and the social context, which, in turn, rests upon the immediate interaction between the author and his audience. The phenomenon of the artwork as both object and subject at once as an independent aesthetic value – impossible outside a multi-faceted interaction with its situation – defines its real political quality. It is reality as a concrete historical condition experienced by society that is the basis and the determining resource for the work of the artist and the creation of active, living culture.

Alexei Penzin /// Uncanny Stability

It is late in the evening in the Moscow Metro but the train is full, nevertheless. An Activist and a Theoretician are riding together. Across from them, there is a glossy advertisement for some kind of pate, flying off into outer space to the slogan “The whole world is not enough!” Beneath it, one can see a public notice from the militia informing all visitors to the city that registration is mandatory. A travelling salesman with a big plastic bag is demonstrating the newest kind of glass cutter, dissecting glass samples for the passengers’ pleasure: “If I’ve caught your interest, don’t hesitate to ask.” A Chinese man sits nearby, flipping through a book with hieroglyphs on the cover. Across from him, a group of teenagers is loudly discussing the newest types of smartphones. A 40-year old man is stretched out sleeping on one of the benches at the back of the car. An empty beer bottle rolls back and forth on the floor to the rocking of the train.

Theorician: So how many new members have joined your organization lately?

Activist: Not many, only a few. But they are becoming more and more active and conscious!

Theorician: Remember how five or six years ago, everyone was talking about a “shift to the left.” It seemed as though “protest potential” were haunting society as a whole, and that these potentials would only have to be harnessed properly. Just take those desperate manifestations against the monetization of pensioner’s privileges. Liberal intellectuals of the older generation accused us of conforming to a general trend. We answered that it wasn’t just fashion and not just another “discourse,” but the action of a reality that they were refusing to acknowledge! We talked a lot about the left’s “counter-hegemony” in politics and culture. But where is all of this today? Nothing has changed one single bit.

Boris Kagarlitsky /// Reactionary Times

The end of the 20th century brought on the complete negation of everything that gave it content and meaning. It was no coincidence that the fashionable philosopher Francis Fukuyama took to writing on the end of history. There was massive rejection of the many ideals that people fought and died for. The slogans of the bygone epoch were subjected to ridicule and declared meaningless. It seemed that some strange magic had turned back the hands on the clock by one hundred years, not only stopping the clockwork, but also breaking the clock entirely to prevent it from ever ticking again.

Of course, the 20th century’s technologies were not lost. But its cumulative social experience sank to oblivion.

The 20th century was a century of struggle for socialism, a struggle that proved tragic, and bloody, largely leading to failure. In the final analysis, it produced a “universal certainty” that capitalism was the only possible, natural, and eternal form of human coexistence. The 20th century began with the Russian revolution and ended with capitalism’s restoration. The Byzantine double-headed eagle once again took wing. Adam Smith, though already outdated in the late 19th century, was elevated to the throne of absolute truth in the realm of economic theory. But most importantly, politicians, ideologues, and intellectuals who had made careers of propagating socialism now became its chief denouncers.

Alain Badiou /// The Saturated Generic Identity of the Working Class

[Alain Badiou gave this interview on the occasion of a conference titled “Is a History of the Cultural Revolution Possible?” The conference was held at the University of Washington in February, 2006. Most of the following questions were prepared by Nicolas Veroli, who could not be present. Diana George conducted the interview.]

This text first appeared in October 2006

Q: I’d like to ask you about your political and intellectual trajectory from the mid 60s until today. How have your views about revolutionary politics, Marxism, and Maoism changed since then?

Badiou: During the first years of my political activity, there were two fundamental events. The first was the fight against the colonial war in Algeria at the end of the 50s and the beginning of the 60s. I learned during this fight that political conviction is not a question of numbers, of majority. Because at the beginning of the Algerian war, we were really very few against the war. It was a lesson for me; you have to do something when you think it’s a necessity, when it’s right, without caring about the numbers.