There are no translations available.

Thomas Campbell // A Senseless Fax from Halifax: Nina Gasteva’s “Silent Dance”

During the only extended conversation I have had with Nina Gasteva, she told me how – during perestroika, I think, or perhaps earlier – she and her husband had lived in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Her husband represented the Soviet merchant (or fishing?) fleet in Halifax, and Nina took up dancing there as a way to stave off boredom and otherwise survive in an alien environment. When I first saw this video of a performance in December 2009 by Nina and her friends outside the entrance to the Petersburg Sea Port, I recalled this conversation. It occurred to me that “Silent Dance” was a kind of a message from Halifax to the regime that got Nina’s husband fired from his job, the event that was the immediate occasion of Nina’s initial solo protest performance outside the sea port in October 2009. I don’t mean the real Halifax: I’ve never been there, and God only knows what really goes on in that fabled land. What I mean is the near-absolute incommunicability between “the current regime” in all its manifestations and ad-hoc attempts at grassroots solidarity on the part of union activists, antifascists, environmentalists, lovers of threatened old buildings, and ordinary citizens outraged at everything from police abuse to the dismantling of the last vestiges of the (post-)Soviet welfare state. Such protests are both more frequent than you would imagine if you’re transfixed by the overdetermined, nonstop performance known as “sovereign democracy” (the latest chapter in Russia’s centuries-long elaboration of the police state) and as likely to make an impression on the body politic and its media gatekeepers as a petition written in invisible ink and faxed in from Halifax. And by “regime” I mean more than this Putinocracy. In the first instance, the regime is the place where Nina and her friends perform their dance: as a guard heard off-camera at the beginning of the video points out, the port is a rezhimnaya territoriya – literally, a “regime territory,” that is, a restricted zone, where the general public, much less a group of contemporary dancers in hats, scarves, and coats, is not expected to show its face. This regime of “regime territories” is also a regime established and reinforced by “violent entrepreneurs” (to borrow sociologist Vadim Volkov’s coinage), figured here both by the armored car (complete with a Kalashnikov-toting passenger) seen pulling up to the gates as the dancers sway imperceptibly as trees in the icy breeze, and Nina’s reference to corporate raiders, whose dirty work is often finished in Russia by armed, masked men, sometimes in state uniforms. The effect of this top-to-bottom, violent securitization and overmapping of physical and virtual public space is, of course, stifling. It will sound like a cliché to say that the only way we can oppose this regime is to organize fragile, “senseless” gestures of solidarity within that space. When, however, this video was shown during the exhibition When One Has to Say “We”: Art as the Practice of Solidarity, at Petersburg’s European University this past spring, it elicited a spontaneous outpouring of unfeigned joy and astonishment among audience members, which is not an easy feat in a city whose cynical inhabitants have seemingly seen too much of everything. Since I was one of that tiny, joyful crowd I can explain why we were able to instantly read Nina’s senseless fax from Halifax and why it felt to us like a minor breakthrough. Like the “friendship” that, before this performance, Nina had suspected didn’t exist, true solidarity is the self-organization of bodies (and hence of spirits) who feared they had nothing in common right in the midst of those territories where the regime wants to have nothing in common with them and for them to have nothing in common with each other.

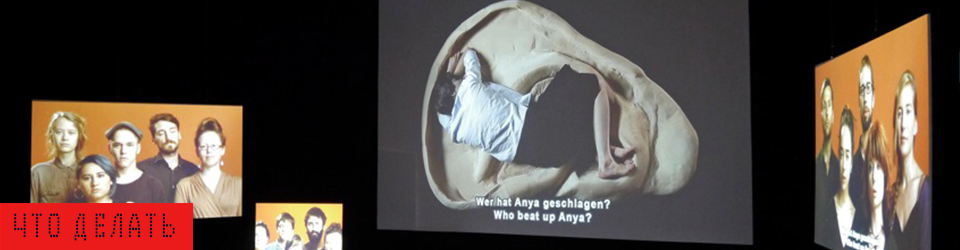

Electrification of Consumers Brains // a video work by Zanny Begg & Dmitry Vilensky, 2008

Choreography: Nina Gasteva

Animations: Zanny Begg

Capitalism makes us so stupid that we associate being with having.

Karl Marx

The most powerful institution of contemporary capitalism is neither the state nor the different coercive machines of labor but consumerism. It could even be argued that communism was ultimately subsumed by our desires to own and consume. When any of us goes to the supermarket we find ourselves in a utopian space: magical things constantly present themselves to our gaze. We can return to an old critique and argue that it is just commodity fetishism and we’re justified in criticizing people for being satisfied with so little. People settled for the lesser, however, because the lesser also contained the greater. Consumerist and technological utopias are being realized in a way that’s the direct opposite, as it were, of actual utopia. It’s like a caricature of any authentic utopian desires.

How are we able to attack this most attractive utopia of the capital? We return to Guy Debord’s critique of commodity fetishism in Society of Spectacle as it was developed on the cusp of the transition to post-Fordist production – a time when production was transformed from the production and circulation of things, to the production and circulation of ideas. Consumerism within this context became less about the purchase of goods then the purchase of lifestyles, dreams, personalities, and hopes.

Today the text of Debord appears like ciphered, forgotten knowledge whose language is understandable just for a few people – tragically it reminds us of the language of the Russian avant-garde that was supposed to be open to everyone and finally after the Russian revolution was perceived by masses as something alienated from any everyday meaning.

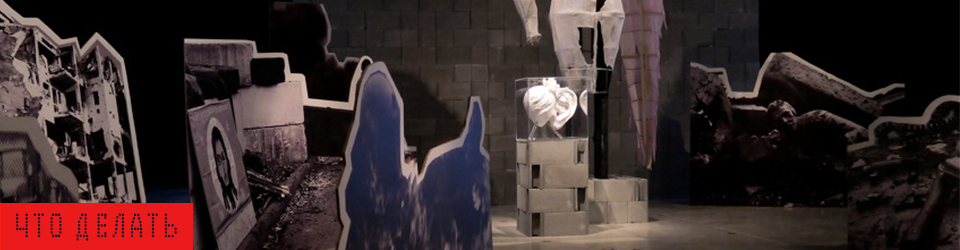

In our performance we wanted to create a situation when normal reality of everyday shopping would be interrupted by strange interventions of a group of sandwich people carrying placards with sentences from Guy Debord. Of course we did not think that this intervention would be able to raise the consciousness of everyday East-German people shopping on Saturday.

But we hoped that this work would explore some of the latent possibilities still contained within the critique of consumerism. Our performance operates as a counter spectacle, momentarily creating a break within the cycle of consumption – symbolic blockade of the entrance to the shopping mall. Through this we hoped to raise the still urgent need for a deeper break with the counter utopia of consumption.

This film is based on an action in public space by Chto Delat? realized in the frame work of the Project “Die Elektrifizierung der Gehirne” at Motorenhalle, Dresden in September 2007.

Love at the Supermarket, 2009

Choreographers and dancers: Mikhail Ivanov, Gasteva Nina

Playwright: Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya

Researchers: Factory of Found Clotes

Dance theatre: Dina Husein

Sociologists: Svetlana Yaroshenko, Olga Chepurnaya

Displaced Persons, 2007

Idea: Mikhail Ivanov, Gasteva Nina, Ammola Juli

Dancers: A. Kadruleva, M. Ivanov, N. Gasteva

Music: Mikhail Ivanov

Noise and Silence, 2005

Choreographers: Mikhail Ivanov, Gasteva Nina

Music: Richard Doiche

Dancers: A. Ignatyev, A. Panchenko, A. Kadruleva

Radiodance

Idea and performance: Nina Gasteva

Music: Peter Chaikovsky

Iguandance

Idea and Performance: Nina Gasteva