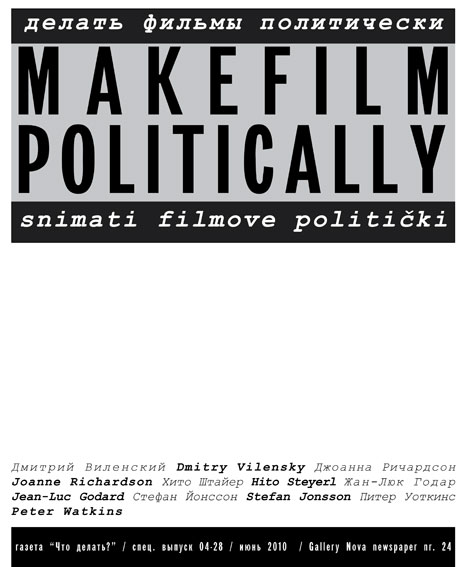

#04- 28: Делать фильм политически

Чтобы смотреть pdf этого выпуска нажми в центре нижеследующего поля

British Sounds. Transcript of the film by J-L Godard

There are no translations available.

BRITISH SOUNDS*

In a word, the bourgeoisie creates a world in its image.Comrades! We must destroy that image!A spectre is haunting Britain: the spectre of communism. All the forces of the old and new imperialism have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: British Petroleum and pop music, the Eurodollar and anti-trade union laws, Elizabeth the dunce and Wilson the traitor.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eurodollar

Eurodollars are time deposits denominated in U.S. dollars at banks outside the United States, and thus are not under the jurisdiction of the Federal Reserve. Consequently, such deposits are subject to much less regulation than similar deposits within the U.S., allowing for higher margins. The term was originally coined for U.S. dollars in European banks, but it expanded over the years to its present definition: a U.S. dollar-denominated deposit in Tokyo or Beijing would be likewise deemed a Eurodollar deposit. There is no connection with the euro currency or the euro zone.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_Wilson

The continued relevance of industrial nationalisation (a centerpiece of the post-War Labour government’s programme) had been a key point of contention in Labour’s internal struggles of the 1950s and early 1960s. Wilson’s predecessor as leader, Hugh Gaitskell, had tried in 1960 to tackle the controversy head-on, with a proposal to expunge Clause Four (the public ownership clause) from the party’s constitution, but had been forced to climb down. Wilson took a characteristically more subtle approach. He threw the party’s left wing a symbolic bone with the renationalisation of the steel industry, but otherwise left Clause Four formally in the constitution but in practice on the shelf.

[…]

With public frustration over strikes mounting, Wilson’s government in 1969 proposed a series of changes to the legal basis for industrial relations (labour law) in the UK, which were outlined in a White Paper “In Place of Strife” put forward by the Employment Secretary Barbara Castle. Following a confrontation with the Trades Union Congress, which strongly opposed the proposals, and internal dissent from Home Secretary James Callaghan, the government substantially backed down from its intentions. Some elements of these changes were subsequently to be revived (in modified form) during the premiership of Margaret Thatcher.

[…]

A number of liberalising social reforms were passed through parliament during Wilson’s first period in government. These included the abolition of capital punishment, decriminalisation of sex between men in private, liberalisation of abortion law and the abolition of theatre censorship. The Divorce Reform Act was passed by parliament in 1969 (and came into effect in 1971).

[…]

According to one historian, “In its commitment to social services and public welfare, the Wilson government put together a record unmatched by any subsequent administration, and the mid-sixties are justifiably seen as the ‘golden age’ of the welfare state”.

Дмитрий Виленский /// Что значит делать фильм политически сегодня?

1. Старые вопросы

Сегодня, через 40 лет после публикации знаменитых тезисов Годара, важно заново расмотреть старые вопросы в ситуации, когда радикально изменились основы производства и дистрибьюции фильмов.

Ты меня любишь? Да я люблю твои глаза, люблю твой рот, люблю твои колени, люблю твою задницу. Значит, ты любишь меня целиком? Да. А ты? Для кого и против кого сделан такой фильм, как «Всё в порядке»?

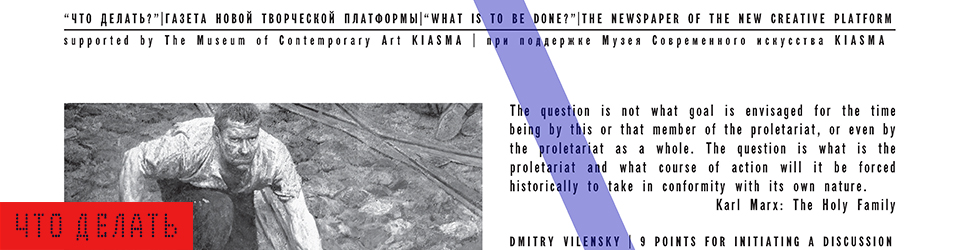

При этом, важно начать с признания факта, что искусство (и в особенности искусство, основанное на кинематографическим языке) способно обнаруживать и с особой силой репрезентировать самые острые вопросы общественного развития. Развитие истории есть результат политического противостояния различных групп людей, отстаивающих не просто свое право на высказывание, но на свое понимание будущего. Продолжать политический проект сегодня это значит, прежде всего, задаться старым вопросом: «кто является субъектом исторического развития и познания?» и попробовать актуализировать однозначность старого ответа «это сам борющийся, угнетенный класс» (Беньямин)

Хито Штайер /// Смутность документалистики

Я отчетливо помню одну странную трансляцию несколько лет назад. В один из первых дней вторжения США в Ирак в 2003 году ведущий корреспондент CNN ехал в бронемашине и, ликуя, вел прямую трансляцию с помощью камеры мобильного телефона, выставленного наружу. Он восклицал, что такого прямого репортажа еще никто никогда не видел. И это была сущая правда. Потому что на этих кадрах почти ничего не было видно. Единственное, что можно было разглядеть из-за плохого разрешения – это зеленые и коричневые пятна, медленно движущиеся по экрану. На самом деле, картинка выглядела как маскировка военного невроза; оставалось лишь догадываться, что эти абстрактные композиции должны были изображать.

Являются ли эти кадры документальными? Если пользоваться конвенциональным определением документального, ответ на этот вопрос очевиден: нет. Они не имеют никакого сходства с реальностью; у нас нет никаких оснований судить о том, показана ли здесь реальность в сколько-нибудь объективном ключе. Но одно совершенно ясно: они выглядят достаточно реальными. Несомненно, многие зрители полагают, что перед ними документальные кадры. Аура их подлинности есть прямой результат их нечеткости.

Igor Chubarov /// Participation and/or Manipulation: The Communicative Strategies of Eisenstein and Vertov in the LEF

There are no translations available.

It’s all a matter of confronting the visual elements one way or another. It’s all a matter of intervals.

Dziga Vertov, “Kinoks: Revolution”

The journal of the Left Front of the Arts, LEF, was where the fathers of Soviet and world cinema, Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov, first announced their theoretical projects. It was still difficult, however, to sense in these brief manifestos (“Montage of Attractions” and “Kinoks”) the principal differences in how the two men saw the nature and tasks of (Soviet) cinema. These would become apparent later, in the late twenties, and would be impartially discussed in the pages of New LEF.

Their approaches might be crudely summarized as affective-manipulative (Eisenstein) and machinic-democratic (Vertov).

These stances made absolute two discrete aspects of the aesthetic doctrine of productionist art as developed within the LEFnamely, a notion of arts goal as the sensual manipulation of the emotions of the viewer, listener, and reader versus the view of art as life-construction involving the creative participation of everyone.

It was no easy task to find a balance between these stances towards leftist art. For the LEFtists, considerations of craft and professionalism marked the limits of democratization, while the limits of professionalization itself were found in democratizations demand that the model of art making as a closed caste of priests and teachers of the people be rejected.

Hito Steyerl /// In Defense of the Poor Image

The poor image is a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard. As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.

The poor image is a rag or a rip; an AVI or a JPEG, a lumpen proletarian in the class society of appearances, ranked and valued according to its resolution. The poor image has been uploaded, downloaded, shared, reformatted, and reedited. It transforms quality into accessibility, exhibition value into cult value, films into clips, contemplation into distraction. The image is liberated from the vaults of cinemas and archives and thrust into digital uncertainty, at the expense of its own substance. The poor image tends towards abstraction: it is a visual idea in its very becoming.

The poor image is an illicit fifth-generation bastard of an original image. Its genealogy is dubious. Its filenames are deliberately misspelled. It often defies patrimony, national culture, or indeed copyright. It is passed on as a lure, a decoy, an index, or as a reminder of its former visual self. It mocks the promises of digital technology. Not only is it often degraded to the point of being just a hurried blur, one even doubts whether it could be called an image at all. Only digital technology could produce such a dilapidated image in the first place.

Dmitry Vilensky comix Godard comments Tout Va Bien

There are no translations available.

Tom Sherman /// Vernacular Video

There are no translations available.

What Are the Current Characteristics of Vernacular Video?

― Displayed recordings will continue to be shorter and shorter in duration, as television time, compressed by the demands of advertising, has socially engineered shorter and shorter attention spans. Video-phone transmissions, initially limited by bandwidth, will radically shorten video clips.

― The use of canned music will prevail. Look at advertising. Short, efficient messages, post-conceptual campaigns, are sold on the back of hit music.

― Recombinant work will be more and more common. Sampling and the repeat structures of pop music will be emulated in the repetitive deconstruction of popular culture. Collage, montage and the quick-and-dirty efficiency of recombinant forms are driven by the romantic, Robin Hood-like efforts of the copyleft movement.

― Real-time, on-the-fly voiceovers will replace scripted narratives. Personal, on-site journalism and video diaries will proliferate.

― On-screen text will be visually dynamic, but semantically crude. Language will be altered quickly through misuse and slippage. Will someone introduce spell-check to video text generators?

― Crude animation will be mixed with crude behaviour. Slick animation takes time and money. Crude is cool, as opposed to slick. Slow motion and accelerated image streams will be overused, ironically breaking the real-time-and-space edge of straight, unaltered video.

― Digital effects will be used to glue disconnected scenes together; paint programs and negative filters will be used to denote psychological terrain. Notions of the sub- or unconscious will be

objectified and obscured as quick and dirty surrealism dominates the creative use of video.

― Extreme sports, sex, self-mutilation and drug overdoses will mix with disaster culture; terrorist attacks, plane crashes, hurricanes and tornadoes will be translated into mediated horror through vernacular video.

Oliver Ressler /// “More visibility to activist practices…”

There are no translations available.

I began to make films because of I was interested in forms that allow the presentation of artwork beyond the boundaries of art, a field I sometimes find restrictive. The majority of my films could be understood as attempts to afford more visibility to activist practices and social movements by describing actions, organizational forms, possibilities of agency, and underlying theories from the perspectives of the protagonists involved. Since my films do not take a “neutral” stance, they are often accused of being “partisan,” and this is something people often hold against me. However, I doubt that this “neutral” stance is even possible, since the very definition of “neutrality” derives from social power relations.

While the choice of interlocutors is influenced by the desire to transfer contents into a film, an equally important aspect is to provide certain people with a strong, self-confident position of the speaker, thus supporting their political concerns and activities. The protagonists speak in produced settings, opening a space of communication and public. A number of my films pursue the conceptual approach of using interview outtakes as the sole carrier of information, consciously leaving out voice-over commentary and bridge texts, producing the film with nothing more than the montage of these outtakes. This method gives some spectators the unintended impression that the interlocutors statements are overdetermined, and that the film does not question their positions enough.

Florian Zeyfang /// “The Two Avant-Gardes…”

There are no translations available.

If one approaches the ubiquitous Jean-Luc Godard from the “other side,” the other of Peter Wollen’s “Two Avant-gardes,” it seems that the experiment is what made it possible (for Godard and others) to make film politically in an ideal film world. What did this mean to experimental filmmakers? In how far is (and was) their work political?

In The Two Avant-gardes, an essay that appeared in Studio International in November 1975, Peter Wollen describes the discussions between two avant-garde movements. The filmmakers he mentions the auteurs in France and a few Germans are on one side, while the co-ops – experimental filmmakers who come from art, most of them from New York and England are on the other. For the purposes of this small contribution, the debate between these two side can be summed up as follows: the filmmakers accused the co-ops of being elitists; the co-ops refuted this with an attack on the traditional form, whose retention would make real change impossible.

In fact, this debate has its history, if one looks at Eisensteins rather traditional narratives only interrupted by short experimental sequences and reads it in relation to Dziga Vertov, whose films Eisenstein criticizes as being camera games and nonsense. But it was precisely Vertovs enthusiasm for formal experiment that made him into the forerunner of Cinéma Vérité AND experimental film. Eisensteins influence on Jean-Luc Godard is just as well-known as his love for Vertov, as manifested in the foundation of the Groupe Dziga Vertov (with Jean-Pierre Gorin and others). Godard was to radicalize Eisensteins concept of montage, breaking it open with camera experiments, though by that time, he had become an unknown to most of the audience.

Christiane Post and Michael Schwarz /// The Desire for Industrialization or the Quest for Happiness

There are no translations available.

In one of his essays [1], Jacques Rancière asks: what type of fiction is the genre of documentary film? His answer is that a documentary is not the opposite of a feature film only because it presents images of everyday life or evidence from archives instead of falling back on actors interpreting a fabricated story. It is rather a different mode of cinematographic fiction, a different way of constructing a plot, breaking down a story into sequences or assembling shots to form a story, of prolonging or condensing time. According to Rancière, a documentary film is both more homogenous and more complex. More homogenous because the person who conceives the film is also the one who realizes it, documentary cinema is thus the epitome of the author film; and more complex because sequences of heterogeneous image material are usually connected.

Our piece combines sequences from Dziga Vertovs films ENTHUSIASM (The Donbass Symphony) (1930) and THREE SONGS ABOUT LENIN (1934) with images from Aleksandr Medvedkins FILM-TRAIN (1932 / 33) and his feature film HAPPINESS (1934), setting them in relation to one another by means of montage. [2]

The films of Medvedkin and Vertov document the attempt to directly and also critically intervene in the production process via the medium of film, on the one hand through interviews with workers, film screenings and on site discussions [3], on the other by means of production propaganda. Apparently, both filmmakers were motivated by the desire to pursue happiness through rapid industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture, pointing out grievances on the huge construction sites, factories, and kokhoz farms of socialism, working toward their solution, [4] and predicting an idealized future. [5]

Two cycles of our collage are dedicated to this utopian illusion; in them, sequences from Vertov and Medvedkins film are juxtaposed through cross-fades. [6]

However, the Russian filmmakers efforts to stimulate the economy in the framework of the first five-year plan remained purely illusionary, especially insofar as happiness is concerned, since they did without any psychological or biological clarification of the mechanisms of desire or happiness in the human organism, either bracketing these out entirely, or relating them to the simplistic model of the conditional reflex. The relationship between economy and hedonistic emotions receives a far more differentiated treatment in Thomas Raabs Nachbrenner. [7]

Kerstin Stakemeier /// Revolutionary Reproduction – Productivism and its Recession

There are no translations available.

Already in their own times, Russia’s revolutionary artistic avant-gardes of the 1910s and 20s offered a highly desirable point of reference for artists outside of Russia. Be it for those who were hoping for a subsequent spreading of the revolution towards Europe, or for those who, after the frustration of those hopes in the early 1920s, believed that artistic practices could proceed to form an independent starting point for revolutionary tendencies within bourgeois capitalism.

Even when the rise of fascism in Europe demanded a drastic change of artistic politics from attacking the petit bourgeois sentimentality to countering the fascist aggression, it was the politics of the popular front, issued by the Comintern in 1934, and exilers journals like Das Wort published in Moscow, which served artists on the left in Europe as points of orientation. This was the case in spite the fact that the avant-gardes in Russia had been dragged into passivity years before. The CPSUs decree of april 1932 On the adjustment of all literary- and artistic organisations, officially dissolved all autonomous artist associations into the state-run Union of Sovjet Artists and settled the dispute between the constructivist and productivist artist associations and those whose realism was based on artistic traditionalism in favour of the latter. Already since 1928, the states cultural policies had centralized working permissions for artists so severely, that constructivists like Gustav Klucis had to publicly denounce their commitments and obey to the national unions slogans. In 1938, when Bert Brecht, Ernst Bloch and Alfred Kurella debated the revolutionary capacities of realism for a popular front in Europe in Das Wort, Klucis was arrested. In 1944 he died in a Gulag.

Stretched between affirmation and contestation, the avant-gardes in the East and West may have shared the abstract will to turn art into life (Tatlin), but while in Europe this meant the introduction of everyday objects and subjects into artistic practices without being able to effect an actual challenge of the role art played within bourgeois capitalism, in Russia this possibly meant the dissolution of artistic practices into means-oriented production. Boris Arvatov, one of the major theoreticians of this productivist branch of the constructivist avant-gardes formulated the revolutionary artists assignment in clear terms: The work of the artist-engineer will build a bridge from production to consumption and this is why the organic engineer-like diffusion of the artist into production will, amongst all other things, be an indispensable condition of the economic system of socialism, ever more necessary as the course of socialism is completed.

Christiane Post and Michael Schwarz /// The Desire for Industrialization or the Quest for Happiness

There are no translations available.

>>> I thought I had written this down somewhere in my notebook, but its not there. Maybe I wrote it somewhere else.

>>> Maybe you dreamed it, or maybe you should make sure no ones ripping pages out of your notebooks. They could be stealing your ideas.

>>> In any case, I am interested in the camera. Or what it means to see a camera; the frame that is presumed when one sees a camera.

If you catch these thieves, you might ask them how vision is affected by the mass-distribution of images images captured by cameras, framed by lenses, operated by camera operators and directed by directors and paid for by producers, translated into emulsion, magnetic waves or digital bits, edited by editors and distributed massively by entities with an enormous reach into the spaces we inhabit and travel through?

>>> Youre not talking about seeing a camera, youre talking about just seeing, right? Do you mean how they see the world differently because of the images that exist in it as well as of it? In-and-of the world?

>>> And the structure of those images. What they picture and what they conceal; what they postulate and what they shut down; where they place you and who they ask you to be. Similarly, how do these technological images in turn structure how we see the world? Is our vision technologized?

>>> Okay, Ill do that. Should I record their answers?

>>> Please.

>>> By now, most people know how a camera works, how it sees, or at least most people feel they know this. They dont just see the black piece of equipment on the tripod or the shoulder of the camera-operator, they see something else too: They see a space in front of the camera, a space defined by the framework of the lens and what can be seen through that lens; what can be recorded.