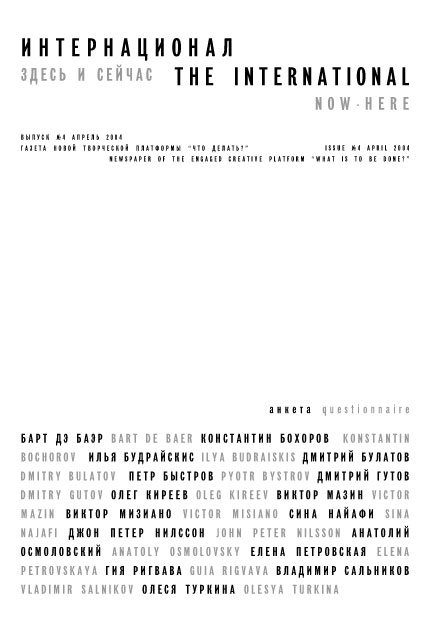

#4: Интернационал здесь и сейчас

1. Which political role can feminism play in the contemporary world?

There are no translations available.

Historically, feminism is closely linked to anarchism and socialism. It was feminism that produced such brilliant figures as Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin, or Emma Goldman, to name just a few. In the final analysis, one can see the politics of woman’s emancipation after the October Revolution of 1917 as this movement’s main success. In the West, many feminist thinkers have understood the struggle for gender-equality as the most consequent strategy for reaching social equality, considering feminism as the most radical form of struggle to come from the Left.

By today, the political struggle of women’s liberation has successfully activated a broad spectrum of “gender identities” and played a decisive role in redefining how we consider subjectivity and the notion of the Other. Many varieties of feminism have become an integral part of the dominant neo-liberal ideology. At the same time, the universal strategy of solidarity between all women in resisting patriarchy has been called into question on a fundamental level. There is good reason to doubt the traditional feminist solidarity, which arguably ignores a great many differences between women all over the world.

For an example, in post-Communist Russia, any reworking of both feminism and socialism seems nearly impossible. At present, both forms of resistance to exploitation have been marginalized from political and social discourse, as Russian society voices its reactionary demand for the “law and order”. Women are attributed with the status of a “leisure class”, as their lack of economic and political independence becomes the norm. The liberalization of the economy has given rise to new, especially inhuman models of sexploitation. All of this demonstrates the pressing need for a critical re-examination of feminist politics both in Russia and in the West.

Which political role can feminism play in the contemporary world?

Which strategies of solidarity between women of different social, national, and ethnic backgrounds are possible today?

Or is it better to shift our focus from the differences between men and women in order to address different universal features, such as political power-relations or social class?

2. Solidarity between women of different backgrounds? Or universal solidarity, based on class?

There are no translations available.

Which strategies of solidarity between women of different social, national, and ethnic backgrounds are possible today?

Or is it better to shift our focus from the differences between men and women in order to address different universal features, such as political power-relations or social class?

Elena Zdravomyslova

Activist//Petersburg

I don’t think that it makes much sense to supply a universal answer to the quesiton of whether to give a priority to feminine solidarity or to any other kind of status-solidarity. I feel that solidarity “pulsates” in dependance of the social problems at hand. I immediately experience solidarity when women are prohibited from singing on a stage in some country because of their sex, when I hear people legitimizing rape, when I find out that a schoolteacher announces that girls are – by nature – less intelligent than boys, when girls are deprived of the chance for higher education some place in Central Asia… However, other contexts will activate other aspects of identity, leading to the solidarity of class, age etc.

Martha Rosler

Artist//New York

Feminism insists on the importance of a series of social “becomings” or processes of transformation rather than simply an improved status for women. Feminism, it is true, has already potentiated the recognition of previously “invisible” subjectivities and subject positions, a process that, in turn, has gone beyond the crucial questions of gender to also allow for post-colonial recognitions of the Other. The necessary solidarity of women in the face of patriarchy, thus, is only part of the story, in the face of growing income disparities in every area of the globe and the rapid pace of neo-imperialist “globalization” of labor, including the increase in sexual slavery that sends women and children across borders to the developed North and West from the former East Bloc and the so-called Third World of the global South.Feminists have traditionally included demands that affect poorer women (and children) as part of their agenda, providing a place for those women and children to voice their own concerns and provide testimony and make demands. This is the feminist solidarity that I recognize, not a reductively universalizing one. At the same time, I believe enough in universal human rights to insist that social practices in “traditional” societies (or social sectors) other than my own that damage women, such as genital cutting and mutilation, or purdah, bride burning, child marriage, and other horrors, should not be treated as local customs worthy of silent respect but rather should be investigated as onerous customs that impede women in those societies. Unlike religious missionaries and arrogant “civilizers”, what is required here is a respect for the opinions of indigenous women as well as their suggested solutions, and a long-term commitment to working with them for change.

Keti Chukhrov

Philosopher//Moscow

Are there any chances for feminine solidarity in contemporary Russia? I don’t think so. As paradoxical as it may sound, such possibilities were far more frequent during the Soviet period. In any case, even if the woman was a secondary part of society, the universalizing model of the homo sovieticus was still in effect as something she could share with men. Today, business (i.e. finance) serves as the symbolic model for reaching equality. Some say that during the post-Perestroika period, women received their independence, along with the right to self-determination and the right to display their own inventiveness. All of this may be true. However, if one examines the sources of the start-up capital in the feminine business-world, one sees that this capital was probably a gift, and what’s more, a gift presented by a man to a woman on the strength of her sexual characteristics and not her qualities as a business partner. To put it differently, woman’s business in Russia is still highly eroticized. In professional life, women are likely to exaggerate their feminine qualities, viewing other women as competitors. In this situation, there can hardly be any talk of solidarity as far as women are concerned.

Katy Deepwell

Editor, critic//London

Do I believe that women can work together for social change and that solidarity and political and social alliances are possible? Certainly, but like any coalition, such co-operation relies on mutual respect and trust, which patriarchy and women who believe that the current political and social arrangements are the best (ie neo-liberal consumer capitalism) do not value. Without trust and mutual respect between women, regardless of their background, education, age, sexual orientation, etc, women will be unable to work together for any form of change. Is gender enough to form such coalition? For me, this depends on the problem and the skills in organising a campaign or a movement for social change. Women collectively have supported so many political and social movements as strong factions: as abolitionists, Cuban rebels, in nationalist liberation struggles, in many civil rights movements. Women have hoped these movements would free them but they have always been bitterly disappointed by the low regard in which their male colleagues held them and their constant complaint that the “larger” struggle was the only goal and women’s liberation or demands constituted a minor issue to be resolved after the revolution.

Olga Lipovskaya

Activist//Petersburg

Searching for strategies of solidarity is an extensive and continual process. It takes place within the framework of international organizations and through the exchange of information between social and political groups of women all over the world. This exchange uses the resources of big international institutions. An especially striking example of this kind of solidarity can be found in the anti-war organization “Women in Black”. Aside from regularly www protests, its members support one another in different countries such as Israel and Palestine, or Serbia and Croatia etc.

Ekaterina Degot

Critic, curator//Moscow

The discourse of the “Other” has been very harmful in all of its variants, be they synthetic-deconstructivist or rehabilitational. The Other does not exist. What we need today is a reassertion of the subject’s universal heroism, not as androgyny, but as something abstracted from gender (and ethnos). This abstraction DOES NOT mean any coincidence with “masculinity”. People who identify themselves as to whether they are women or men fail to understand that this status is no more important that than a congenital illness like asthma or stuttering: it simply conditions the bounds of our possibilities; it is something to be taken into account, but little more. Solidarity between women of different social or ethnic backgrounds is possible and necessary in the same measure as solidarity is necessary between the ill. Incidentally, there is no place better suited toward solidarity than a hospital.

Love Corporation

Artist group//Iceland

Respect and creative dialogue between women of different backgrounds is the key. All individual characteristics and peculiar wisdom of different social backgrounds should be cherished. Or is it better to shift our focus from the differences between men and women in order to address different universal features, such as political power-relations or social class? People should talk to one another with a focus on learning more about life. Man and woman working together is the ideal.

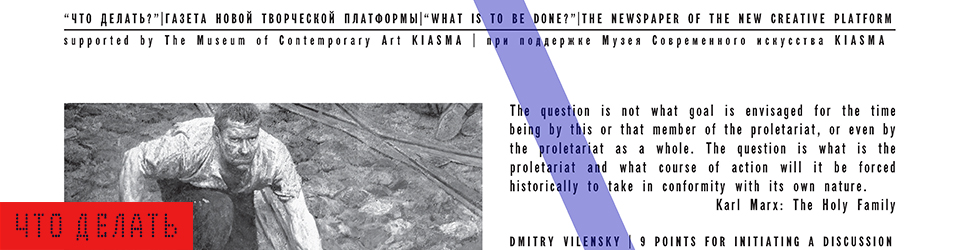

Question 1 /// How important is it to appeal to the Communist roots of globalization today?

“Hold high the banner of the Communist International!” Anyone who grew up in the Soviet Union remembers this call, repeated ad naseum. Does this call mean anything at all today?

Today’s situation is usually sketched out in poetic descriptions of the opposition “multitudes vs. Empire” or even in gleeful Lacanian Leninism from Slovenia. While such intellectual radicalizations may briefly inflame narrow circles of international activists, such local flash-fires are quickly snuffed out, as neo-conservatism and fundamentalism make their explosive appearance. In this sense, the legacy of the Marxist International – though still appealing and even sexy – seems compromised. Historically, it was a response to the global expansion of capitalism and its seizure of new market territories. Its answer: solidarity between the disenfranchised, be they workers, peasants, or intellectuals, regardless of ethnic, religious, or national location. As such, the International dislocates traditional conceptions of community and resistance. Both now/here and no/where, its utopia is clearly messianic but at the same time – as a philosophy of practical solidarity – it demands tangible results. One of these results is the current process of globalization, which actually rests upon universal movements like the International. This movement is in danger of being forgotten.

Bart de Baer

Curator //Antwerpen

It seems crucial to understand these, and it will be unavoidable, since they remain to be as a potentiality. They may lead to a critical awareness, a possibility to think the future. What seems important to me too is the roots of the Communist roots, the strands of thinking it comes forth from, so that it doesn’t become an isolated image but a multiplicity.

Viktor Mazin

Critic, curator, psychoanalyst // Petersburg

It is important to address a variety of globalization’s roots. In my opinion, the “romantic” boundlessness of capitalization played a far greater role in globalization than the Communist Manifesto. Notwithstanding the tangible historical connection between the International and the transnational corporations, they actually belong to different orders. It is not advisable to mix up an economic order with a political program, all the more since the political program has been discredited, while one might say that the economic order has been given the “green light” in terms of ideology. Any radicalization should not have the effect of eroding this thought, but should also not tarry in the utopia of its activity of resisting the state’s ideological apparatus. In my view, it is important to develop a poly-ethical position rather than the desire to influence a multitude of millions, in symmetry to the desires of the controlling bureaucrats, who serve the transnational corporations.

Question 2 /// Is it possible to break out of exclusive global representation?

The pathos of international solidarity was a key component for many a modernist movement, including Dadaism, Futurism, Fluxus, the Situationist International etc. Despite their aesthetic and practical divergences, they all accentuate the fact that we live on a common planet, where the political boundaries of nation-states do not play any role in defining the processes of the personality’s creative development. Regardless of this internationalist tradition, the system of contemporary art is far from fulfilling the proclaimed ideals of internationalism and solidarity. Many artists and art-professionals have been corrupted by “big events”, international success and trans-national competition. This dictatorial market neutralizes any and all progressive tendencies.

Which chances do you see for the ongoing democratization of art? Is it possible to break out of the framework of market hierarchy and exclusive global representation?

Ilya Budraiskis

Historian, activist // Moscow

The future of contemporary art and its strategies and forms is connected to changing the social context. It seems to me that there are no grounds for singling out the art-system for its cynicism and corruption, even if such accusations may be just. After all, one can apply this form of interrelation to capitalism as a whole. As mass movements grow, updating international solidarity in the face of Neo-Liberalism’s onslaught, they can supply new meanings to the figure of the artist.

Dmitri Bulatov

Artist, curator, critic// Kaliningrad

The growth and preservation of any process depends on physical differentiation. It also depends on a heightened unity of the field. This is how I would characterize the rhizomatic essence of any community’s existence, no matter whether they are artists, activists etc. Note that we are not speaking of solidarity as a constant quality – the community faces each motivation as it arises, forcing the community to change its vector of development each and every time. However, the ideology of “big events” or institutional success does not play any decisive role, in my opinion. I would characterize one of the Rhizomatic International’s attributes as the capacity for self-organized criticism. The combined effect of a multitude of small communities can break into the exclusiveness of global representation. Technological re-tribalization – the gradual reversion of communities into a tribal state, accompanied by a strong technological dominant – is our time’s most important need. Without it, any progressive idea will inevitably become a decorative idiocy, once it takes its place at a trade-fair.

Question 3 /// How important is it today to stop the conveyor of big events?

The pathos of international solidarity was a key component for many a modernist movement, including Dadaism, Futurism, Fluxus, the Situationist International etc. Despite their aesthetic and practical divergences, they all accentuate the fact that we live on a common planet, where the political boundaries of nation-states do not play any role in defining the processes of the personality’s creative development. Regardless of this internationalist tradition, the system of contemporary art is far from fulfilling the proclaimed ideals of internationalism and solidarity. Many artists and art-professionals have been corrupted by “big events”, international success and trans-national competition. This dictatorial market neutralizes any and all progressive tendencies.

How important is it today to stop the conveyor of big events, opting for internationalist work on location instead?

Viktor Mazin

Psychoanalyst, curator, critic//Petersburg

It is impossible to “stop the conveyor” since art is not isolated from life’s other registers. And by the way, this utopian isolation would hardly lead to anything. But I agree that it is necessary to “work on location”. Regardless of what they say about globalization, we all work in specific cultural contexts. Once again, it is necessary to render the meaning of this work from the context that it affects.

Question 4 /// Is it important to consider the experience of new local communities?

Contemporary philosophers and theorists prefer to speak of communities rather than the International, of alternative groupings, pulsing and networking in affectation, eroticized in symbolic exchange. Whether you’re a Punk, a Raver, a Hip-Hopper or even a member of ATAC, radicalization is coded into your way of life. Because you can only be consequently authentic if you drop out from society’s general production in favour of relating to your community. For this reason, such communities are very site-specific. On the other hand, they are only possible thanks to the global language of pop-culture. Today, the experience of such groups appears as an important model for artists in search of the connections between local marginality and global significance.

In how far is it important to consider the experience of new local communities that draw their linguistic legitimacy from global pop-culture? In how far do they influence the development of contemporary art?

Olesya Turkina

Curator, critic//Petersburg

New international communities appear as pockets of resistance; then, pop-culture legitimates them. You might consider art as one of these communities; in some cases, there is a direct connection between art and resistance, as is the case with graffiti. But neither hip-hop, punk nor rap are capable of exerting any real pressure on art; the source of the pressure is actually consumer society. The speed with which consumption makes its appropriations is constantly growing.

Editorial Questions

Historically, feminism is closely linked to anarchism and socialism. It was feminism that produced such brilliant figures as Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin, or Emma Goldman, to name just a few. In the final analysis, one can see the politics of woman’s emancipation after the October Revolution of 1917 as this movement’s main success. In the West, many feminist thinkers have understood the struggle for gender-equality as the most consequent strategy for reaching social equality, considering feminism as the most radical form of struggle to come from the Left.

By today, the political struggle of women’s liberation has successfully activated a broad spectrum of “gender identities” and played a decisive role in redefining how we consider subjectivity and the notion of the Other. Many varieties of feminism have become an integral part of the dominant neo-liberal ideology. At the same time, the universal strategy of solidarity between all women in resisting patriarchy has been called into question on a fundamental level. There is good reason to doubt the traditional feminist solidarity, which arguably ignores a great many differences between women all over the world.

For an example, in post-Communist Russia, any reworking of both feminism and socialism seems nearly impossible. At present, both forms of resistance to exploitation have been marginalized from political and social discourse, as Russian society voices its reactionary demand for the “law and order”. Women are attributed with the status of a “leisure class”, as their lack of economic and political independence becomes the norm. The liberalization of the economy has given rise to new, especially inhuman models of sexploitation. All of this demonstrates the pressing need for a critical re-examination of feminist politics both in Russia and in the West.

Which political role can feminism play in the contemporary world?

Which strategies of solidarity between women of different social, national, and ethnic backgrounds are possible today?

Or is it better to shift our focus from the differences between men and women in order to address different universal features, such as political power-relations or social class?

Feminism strives for equality. But when a woman attempts to reach equality in the contemporary world, she will often adopt a male model of behaviour, becoming forceful, aggressive and conceited. Suddenly, a great number of important human qualities such as patience and the ability to understand the Other appear irrelevant. They are displaced onto the periphery and hidden in privacy; society is apt to experience them as completely unwanted forms of weakness. If this is subjectivity, then many women would prefer not to become subjects. In Russia today, we can clearly see in how far women have been successful in developing their own manipulative practices in order to reach their goals by playing with their “weaknesses” and their vulnerabilities. And men? Even they are hardly free in all their machismo. Real emancipation must free both sexes!

Do you feel that qualities like “vulnerability” will die out as unnecessary capacities?

Or is it possible to engage in a certain revolutionary politics of vulnerability?

How can feminism convince human beings of both genders of the need for emancipation and of the benefits of real freedom?

In the contemporary world, there is much sex and much sentiment, but very little love. All too often, love is defined as a form of uncomplicated romantic relationship, welcomed as a brief interruption in professional and social life. In this case, love is a part of the machine of consumption, an example of how people are unable to deal with their own freedom and how they are incapable of truly accepting the freedom of the Other. On the other hand, love is often experienced as a traumatic addiction, requiring liberation or therapy, since it robs the human being of her-his independance. Is this something we should accept? Or can we search for love as a revolutionary possibility for freeing one another?

The act of love offers a possibility for stepping into a relationship of solidarity and becoming a part of a network of resistance to the capitalist order. Love has always been the fundamental means of breaking the illusion of existential loneliness. Today, it becomes the most relevant way of countering a notion of privacy that is trapped in autistic consumption. In this sense, the notion of love can hardly be confined to the bounds of the couple or the family; once it is opened toward the world at large, love can create communes of resistance and desire.

At the same time, love is a “ordinary” experience of the relation between human beings, men and women alike. This “ordinary” experience is only possible because it can be repeated again and again in the act of giving and liberation, withstanding the urge toward exploitation and consumption. Everyone knows this experience of stepping out to meet the Other. Now, it is time to bring this experience to the politics that define the life of our society.

Does love have any political potential in your opinion?

Do you think that there is anything specific in the feminine experience of love?

Question 5 /// Is international style the only relevant possibility for addressing the local problematique?

The Soviet experience is a unique example of how internationalism was perverted and discredited, as Stalin’s projected realization of “socialism in one country” reduced internationalism to the idea of party-loyalty. Among other things, this doctrine also formed the conception of art “national in form, socialist in content”. This lies in stark contrast to contemporary art in the age of globalization, which has developed the converse ideological recipe for the artwork, executed in a unified style but referring to the parameters of the local situation.

Is international style the only relevant possibility for addressing the local problematique? Is there any space left for creative misunderstandings, lost in translation, experiences that are both subjective and local?

Which experiences have you made in highlighting the uniqueness of a local cultural context as something of general relevance?

Gia Rigvava

Artist//Stuttgart-Moscow

Internationalism was perverted, but not discredited. The Soviet experience was a unique, valuable lesson. It taught us how and what to do, and what not to do. As to for art that is “national in form and socialist in content”, I don’t see anything wrong with it: it was a good formula for that place and time. Here, language was also already being unified in painting and sculpture, combining the genre basics of early European 19th century modernism with the elements of classicism. The style itself differed depending on national aesthetic preferences. I would say that nowadays we have the same situation. Of course, there is one big difference – there is no socialist content. But then again, there is no content at all. Just as socialist politics were trying to fill the work of art with a particular content, capitalist politics drain artworks of any content. All productions of meaning are constantly aborted. The world is cluttered with individualities, whereas presence is not tolerated as an identity. Here, I don’t mean paper-controlled identity, but authentic identity, an identity which has something to say. If people could ultimately tell themselves “I am the one who…” instead of humbly occupying their places in the existing order, it would anticipate a different social climate and we could actually expect something to change.

I myself work on a particular ground – on the territory of a deterritorialized subject. The material I work with is my localized experience. I believe it is generally relevant. What I am doing can be asked anywhere, whenever the discourse of deterritorialization or adjacent discourses are brought into focus. I would say that I am committed to “highlighting” the experiences spotlighted by my identity. I guess I am not too far from the issue of “highlighting the uniqueness of a local cultural context as something of general relevance” which I think is not a wrong idea, it can work when things are done elaborately. But the question is how can any work be done elaborately on the peripheries? There are so many things missing there that unfortunately, usually, one ends up with no more than painful frustration.

Keti Chukhrov, Moscow

Which political role can feminism play in the contemporary world?

The goal is not to achieve simply to achieve legal equality; instead, we need to transform the problem of sex, bringing it beyond the system of binary oppositions. In my opinion, feminism has a great future, since it has proven capable of not only opening discourses on gender and its socio-economic backdrop, but also touches upon an ontological problematique. By asking questions of the feminine sex, feminism also raises questions as to its various modes of co-existing with the masculine part of society. Is the woman really an Other in relation to the (masculine) Others? This is probably one of the most fundamental questions that feminism has been able to ask. For the woman has always been no more than a narrative: she could even be the central object of an artwork, but her ontological status of Otherness, as the existence of the Other, was displaced from society’s communications at large, only to surface briefly in the event of love, which, in turn, could only present itself as an artwork. A contemporary reposing of feminism’s question cannot be reduced to criticizing the masculine or criticizing the feminine. Communication needs to be re-marked in non-binary terms, as does the event that occurs when the two sexes meet, even in this meeting’s erotic option. This does not mean that communication needs to become unisexual or purely based in groups. Instead, it means that we need to get beyond the phantasmal sexual expectations associated with the Other.

Which strategies of solidarity between women of different social, national, and ethnic backgrounds are possible today? Or is it better to shift our focus from the differences between men and women in order to address different universal features, such as political power-relations or social class?

Are there any chances for feminine solidarity in contemporary Russia? I don’t think so. As paradoxical as it may sound, such possibilities were far more frequent during the Soviet period. In any case, even if the woman was a secondary part of society, the universalizing model of the homo sovieticus was still in effect as something she could share with men. Today, business (i.e. finance) serves as the symbolic model for reaching equality. Some say that during the post-Perestroika period, women received their independence, along with the right to self-determination and the right to display their own inventiveness. All of this may be true. However, if one examines the sources of the start-up capital in the feminine business-world, one sees that this capital was probably a gift , and what’s more, a gift presented by a man to a woman on the strength of her sexual characteristics and not her qualities as a business partner. To put it differently, woman’s business in Russia is still highly eroticized. In professional life, women are likely to exaggerate their feminine qualities, viewing other women as competitors. In this situation, there can hardly be any talk of solidarity as far as women are concerned.

Do you feel that qualities like “vulnerability” will die out as unnecessary capacities?

The qualities of vulnerability cannot die, since they are not sexuate qualities but psychological states. Nevertheless, weakness is a symbolic category well-suited to manipulative use by both women and men. In Russia , feminism is not only unacceptable to many men, but also seems intolerable to many women: men actually represent one of the most important stages of a woman’s formative process in both economic and social terms. It is interesting that despite all of the nominal improvements the woman is not capable of refusing her own phantasm, even (or because) it makes her an object, waiting for the man to present her with some selfless gift. This situation’s corruption does not lie in its expectation of such “alms”, but in that women come to expect this gift in the name of their sex; they are incapable of separating their persona from its sexuate projections. In other words, the woman defines herself by cultivating her sexuate traits. Her sex is the motor of her personal semiotic machine.

Or is it possible to engage in a certain revolutionary politics of vulnerability?

Revolutionary politics as well as any form of protest can be constructed according to any semiotic model. The image of vulnerability is one such model. However, this image will hardly be feminine. If it is, we will no longer be talking about politics. I am afraid that politics cauterize or burn out any feminine plasticity completely. This is not because they elevate masculinity above all else. Instead, politics do not tolerate the intimate or the sacrificial image of the Other. In fact, sacrifice is something apolitical. Of course, this brings Antigone to mind. Does she carry out the burial of her brother as a political or a familial claim? Is her protest political, or does it attempt to extrapolate the essence of femininity and every-day feminism, long since realized in the framework of rituals? Unfortunately, this question demands a more extensive answer. As far as revolutionary politics are concerned, it is only possible to play out the revolution by counterpoising a given quality to the system at hand, but not through strategic methods of re-politicization. This counterpoise might consist of becoming vulnerable, becoming an animal, a woman, a bum etc. Yet these have little to do with the “politics of weakness”, which are an oxymoron.

How can feminism convince human beings of both genders of the need for emancipation and of the benefits of real freedom?

The possibility for liberation is something that begins in our minds. The relationship between the sexes, their erotic conflict, is based upon a phantasm. This phantasm is fed by narratives (cinema, literature), history and culture. (There is also dreaming: in dreams, the problem of sex exposes itself in all of its nudity). This is why I can only think of feminist liberation in a futurological key. In the first place, it would lie in freeing ourselves of the phantasm that produces the well-worn consumer clichés of physicality, speech, language, communication, and, finally, socio-economic relationships. Yet this is actually rather utopian, since “liberation” from the phantasm presupposes being freed from the greater part of desire. But desire is actually contemporary consumer-society’s main trick, since its satisfaction creates the illusion of immanent, authentic freedom.

Does love have any political potential in your opinion?

Do you think that there is anything specific in the feminine experience of love?

Love is an ontological problem. It only becomes a problem of gender or politics later on in the game. This is why love is so complex. We should remember how often narratives on love are intertwined with death: the aesthetics of love are thanatographic. In this sense, politics plays the role of an obstacle. Creon’s political demands on Antigone are more than justified. After all, he is trying to keep society’s peace. When Antigone carries out the ritual of burying her brothers, she is not motivated by love, but by a sense of obligation. She sacrifices love in the name of a ritual that serves an older society and its political system, its ancien regime. In the cases of both Creon and Antigone, politics bury love. Creon suppresses his love for his niece in favor of his responsibility to society at large. Antigone’s fulfillment of the ritual burial of her criminal brothers is in a sense also a political act, but it aims at an electorate that has already passed away. In both cases, the projections of love and eros undergo a drastic castration. Is love possible as something that takes place among couples or families, but that is “open toward society”? Probably. But I am afraid that such descriptions are very similar to the notion of a “civil society”. While the civil society is a wonderful institution, it is based on the Kantian ethical paradigm, which is only relevant thanks to its exclusion of any erotic ecstasy.

Nevertheless, communality based on love is possible through an attentive understanding of Christianity (cf. Slavoj Zizek, “13 Attempts on Lenin”). I do not think that the everyday experience of the relationship between people especially if it is only based on respecting the Other has much to do with love. The experience of “stepping out to meet the Other” is not that easy, since help often requires the sacrifice of personal interest. Human love though virtual and universal immediately constructs a hierarchy of greater and lesser intensities. The different intensities in the relationships to objects that come from differing subject are actually what compose love’s most painful problem. Only god can love everyone in equal measure. When it comes to the question of extrapolating love to society, political honesty and revolutionary ideals don’t help much. Let us at least remember the excellent film “The Communist” or Ostrovosky’s novel “How the Steel was Tempered”: like many other similar narratives, they are talking about real physical sacrifice and heroic self-effacement. And yes, this is probably love. Only it has very little to do with sex or gender, not to mention coitus.

Elena Zdravomysleva, Petersburg

Which political role can feminism play in contemporary Russia?

In Russia , like in other countries with transitional economies, the emergence of weak political feminist groups runs parallel to the discursive backlash toward patriarchy. This backlash confirms archaic ideas of the rightness of the male and female; its public sexism and its dreary biologizations of sexual difference are followed by the legitimization of inequality. This is actually the arena in which “our” feminism currently operates. Our main goal is to explain why feminism is such a hobgoblin to Russian intellectuals. What are they so scared of? Why do they laugh feminism off so often, without even trying to understand what it’s all about…

Which strategies of solidarity between women of different social, national, and ethnic backgrounds are possible today?

Or is it better to shift our focus from the differences between men and women in order to address different universal features, such as political power-relations or social class?

I don’t think that it makes much sense to supply a universal answer to the quesiton of whether to give a priority to feminine solidarity or to any other kind of status-solidarity. I feel that solidarity “pulsates” in dependance of the social problems at hand. I immediately experience solidarity when women are prohibited from singing on a stage in some country because of their sex, when I hear people legitimizing rape, when I find out that a schoolteacher announces that girls are by nature less intelligent than boys, when girls are deprived of the chance for higher education some place in Central Asia… However, other contexts will activate other aspects of identity, leading to the solidarity of class, age etc.

Do you feel that qualities like “vulnerability” will die out as unnecessary capacities?

Understanding the Other, the ability to perform emotional labor, the ability to listen: are these weaknesses? Or strengths? If no one were to do this form of work, we would soon be left with nothing but a factory of robots in place of humanity… However, these qualities-resources can become hidden means of manipulation whenever they are declared as secondary, when they are not valued and rewarded according to achievement. Both men and women use the manipulative practices that you describe. Furthermore, they are used by underlings and all of those who are sure that they will be put down and shut up. The tactics of manipulation allow you to reach your goal in a society that will fail to hear you otherwise.

Or is it possible to engage in a certain revolutionary politics of vulnerability?

Of course, these are beautiful words. The revolutionary politics of the weaker sex? The demonstrative vulnerability of geisha-girls and spies? Weakness as an explosive strategy? Having been nominated as the weaker and gentler sex, women either violently reject weakness to step forward with emancipatory pretences, or admit that they are weak, propagating the slogan “You’re the head, and I’m the neck…”

How can feminism convince human beings of both genders of the need for emancipation and of the benefits of real freedom?

Feminism’s point of departure is the fact that patriarchy’s “treasures” are not accessible. The hopes for a masculine protector or an economic provider are ephemeral. Still, the desire to be protected is an undying dream for most Russian women. But counting on help from the strong often leads to complete bankruptcy and collapse. With many of the weaker sex’s representatives, this is often the case. While economic and political fragmentation erase the hope for patriarchy’s benefits, they also preserve and heighten patriarchy’s ills, such as symbolic racism, chauvinism, violence, and dependence. In order to avoid them, we need to reach independence and equality. Of course, the choice is not a simple one to make. But who said that freedom is pleasure? “It’s better to be needed than to be free” this is something I know from experience. A line from a children’s song. However, we can’t count on always being needed by someone. We only need ourselves…The advantage of freedom is the lack of deprivation and the gain of a readiness to cope with problematic situations on one’s own. But there are so many situations like these. What we actually need is a balance of economic and political freedom and emotional dependence, which is actually a part of any human existence’s base. This is why love is a dependency that should not be discarded.

Does love have any political potential in your opinion?

Do you think that there is anything specific in the feminine experience of love?

I find it difficult to talk about love in such categories. I think that love has many faces. Furthermore, the currency of love’s different forms varies according to the different phases of an individual’s life. It is extremely dangerous to politically manipulate emotions, which bring on collective passions, collective love, collective rage, and then, collective guilt, collective atonement… Love is a personal matter, but its political potential is dangerous…

Olesya Turkina, Petersburg

Which political role can feminism play in the contemporary world?

Which strategies of solidarity between women of different social, national, and ethnic backgrounds are possible today?

Feminism was activated in Russian during the early Perestroika, as the social, political and aesthetic orientation-points were shifting totally. On the one hand, the notion of feminism became one of the fashionable “trademark brands” of the new homo sovieticus, reborn immediately under the influence of Western democracy, which brought both freedom and Tampax to Russia . On the other hand, it became clear that feminism was not only in superficial demand, but that it was an integral part of the Western intellectual discourse that was being introduced into Russia at the time. In the late 1980s, as the first feminist conferences and exhibitions were taking place, Victor Mazin and I organized the show “The Textual Art of Leningrad” in Moscow, dedicated to Derrida’s “veil”; in Leningrad , we curated “Women in Art”. One might also remember how stockings were given away at the Bronze Horseman, Petersburg ‘s central monument. In this total mixture, one could also hear invocations like the one that astonished me when I visited the Fifth International Congress of Woman Art Historians in Hamburg in 1991: it was fashionable to address “our Eastern-European sisters”, only recently liberated from Communist captivity. At this point, many saw feminism as something quite aggressive and bellicose. But as strange as it may seem, it was also sexy. This corresponded to an overall feeling that was in the air. The sexuality of feminism conveyed revolutionary drive and fearlessness. Shocking the public with its directness, the first advertisement of hygiene products was very physical and even demonstratively seductive: the eroticism of a child, suddenly discovering sexual difference. In the late 1980s, it seemed that the “new Amazons” were fearlessly and cheerfully sweeping up the leftover principles of Soviet patriarchy. Seen as one of the most effective forces in intellectual life and politics, feminism carried a great deal of utopian hope.

Yet by the mid-1990s, these hopes had collapsed. The consumption machine had crushed the Amazons. The new Russian woman was one of the most important target groups. The market of long legs, pouting lips, perky breasts and buns expanded to hundreds of millions of former Soviet citizens. Simple-heartedly, its marketplace resounded with cries of one the most understandable principles of capitalism: invest in your body by consuming beauty products; these products aren’t only the most affordable investment; they are also the products closest to you. The first TV shows “for women” began to appear, where Maria Arbatova opposed both “traditional” Soviet values as well as the new capitalist way of life. But chaos and employment were spreading, and beauty-salons seemed a far more effective means in the struggle for survival than political demonstrations. Politico-economic stabilization, however, has brought on a new wave of Russian patriarchal discourse. It has been taking place under the advertising slogan “our mom’s so smart”. Smart mom feeds the family with chicken-broth cubes by “Knorr” and does the laundry with “Tide”. Mom is the perfect consumer; she redeems her natural fertility by becoming an insatiable consumer cannibal.

Do you feel that qualities like “vulnerability” will die out as unnecessary capacities?

“Men can only be free if women are free.” Today, this famous axiom by Mao Tse-tung seems more current than ever. Contemporary post-industrial society no longer requires the division of responsibility according to “male” and “female”. The new technologies of the post-Fordian production line no longer require specific “male” qualities of the worker; “house and hearth” have been saturated with smart domestic appliances capable of executing all forms of domestic labor. These innovations were supposed to liberate us from the model of patriarchy, in which the man earns a living while the woman serves him. Nevertheless, notwithstanding the fact that men only rarely equate their lovers to housewives, woman’s journals cradle and lull us with their bed-time-stories of a “perfect union”, in which “feminine duties” are reduced to making the body seductive (with skin-creams, scented baths, massages, or diet pills…), or to producing the “nest warmth” of the home, suffused by the aroma of fresh-baked vanilla pastry.

How can feminism convince human beings of both genders of the need for emancipation and of the benefits of real freedom?

Feminism is capable of liberating human beings (women as well as men) from the demeaning choice of being either a master or a slave. Being different without oppressing or being oppressed.

Does love have any political potential in your opinion? Do you think that there is anything specific in the feminine experience of love?

The political potential of love consists in the personal resistance of which only lovers are capable. Losing yourself in your beloved, refusing all norms and prejudices, and in doing so, breaking free of the dominant order, then finding enough strength to keep from drowning in your beloved’s blinding image, only to be born again with all differences intact. It is only possible to love the Other, the Other in yourself. The lover can never be an obedient cog in the socio-political machine, controlled by the advertisements of insatiable consumption. She-he is an agent of more vital force, capable of smashing the cynical order of reality.

Love Corporation, Iceland

Which political role can feminism play in the contemporary world?

We see feminism as a strong tool to strengthen individualism and self confidence. If people feel that they are in charge of their life they function better in all ways. If people stop looking at themselves as victims but start to figure out ways to control their surroundings and their lives everything becomes more optimistic and better.

Which strategies of solidarity between women of different social, national, and ethnic backgrounds are possible today?

Respect and creative dialogue between women of different background is the key. All individual characteristics and peculiar wisdom of different social backgrounds should be cherished.

Or is it better to shift our focus from the differences between men and women in order to address different universal features, such as political power-relations or social class?

People should talk together with the focus to learn more about life. Man and woman working together is the ideal.

Do you feel that qualities like “vulnerability” will die out as unnecessary capacities?

To us feminism strives for equality but not uniformity. The politics of feelings are super important and should not be suppressed. If you feel free to express your feelings in a healthy manner it makes you feel better and stronger.

Or is it possible to engage in a certain revolutionary politics of vulnerability?

All artistic expression creates certain vulnerability. Artistic expression at it’s strongest addresses universal human experience on a personal level. So telling the truth can continue to be a revolutionary act as it has always been.

How can feminism convince human beings of both genders of the need for emancipation and of the benefits of real freedom?

By showing this in reality and a encouraging self-confidence in all manner. And refusing to be put into categories or labeled in anyway.

Does love have any political potential in your opinion?

Yes. Love conquers all!

Do you think that there is anything specific in the feminine experience of love?

We hope that every human being experiences something specific and personal in love throughout their life.

Olga Lipovskaya, Petersburg

Which political role can feminism play in the contemporary world?

Seen from the vantage of contemporary thought from the West, feminism’s goal can be summarized as follows: the discovery, recognition and preservation of the multiplicity of feminine identities, in all of their socio-political aspects and their variation of identity. Racial, ethical, religious or cultural differences are just as important as individual aspects: differences of the body, of psychology, or of sexuality and so on. However, it is also feminism’s aim to search for common goals for women in struggling with the dominant culture of patriarchy. The results is a continual process of mediation between two tendencies that would seem to contradict one another.

Which strategies of solidarity between women of different social, national, and ethnic backgrounds are possible today?

Or is it better to shift our focus from the differences between men and women in order to address different universal features, such as political power-relations or social class?

Searching for strategies of solidarity is an extensive and continual process. It takes place within the framework of international organizations and through the exchange of information between social and political groups of women all over the world. This exchange uses the resources of big international institutions. An especially striking example of this kind of solidarity can be found in the anti-war organization ” Women in Black “. Aside from regularly www protests, its members support one another in different countries such as Israel and Palestine, or Serbia and Croatia etc.

Do you feel that qualities like “vulnerability” will die out as unnecessary capacities?

The quality of “weakness” is no more than a part of patriarchal ideology as far as women are concerned. Opposed to dominance and aggression, qualities that are self-evident in people of both sexes, weakness is part of a gender-dichotomy that facilitates different paths of forming these qualities in boys and girls. To simplify, the boy’s aggression is condoned and even encouraged as self-realization, while the little girl’s aggression is repressed. I agree that emancipation should concern both sexes; as a process, it is indeed taking place in developed regions or countries like Scandinavia or Germany , where the social-democratic or liberal models of society have been realized. As a result, we know many examples of how men are more actively involved in caring for their loved ones or their children, and of how women are represented in society’s power structures. I am convinced that this is one of the factors that determined the successful socio-economic of these countries to date.

Or is it possible to engage in a certain revolutionary politics of vulnerability?

Rather than talk about “the politics of weakness”, I would prefer to operate with the notions of universal goodness and justice, notions that feminist thinking extends to women as a class. I do not think that it is necessary to reinvent the bicycle: these ideas are essential to Christianity, Buddhism and many other philosophical schools. Thank god we have a choice: some might prefer Confucianism, while I feel better about Buddhism, for an example, about its ideas of non-violence, “edited and enhanced” by feminist theory.

How can feminism convince human beings of both genders of the need for emancipation and of the benefits of real freedom?

Again, feminism has not thought of anything new; it has only spread general liberal ideas in relation to women. On the whole, feminist theorists have made a great effort to deconstruct the mechanisms of patriarchy as a culture that keeps the woman in a subordinate role on all levels of existence. These effort have been undertaken with a great deal of success for the last 50 years, producing a great number of new tendencies and directions in the liberal arts. More importantly, their praxis has shown that the equality of human beings is beneficial to society as a whole. Is it really necessary to give examples of how gender-equality results in a better quality of life? Compare Afghanistan or Tadzhikistan to Sweden or Norway . Or maybe we should look at the reaction of Russian women, when someone wants to introduce polygamy to Russia ? It may be that our women have not yet realized how advantageous independence and autonomy really are, but do they really become the second or the third wife?

Does love have any political potential in your opinion?

Do you think that there is anything specific in the feminine experience of love?

I think that there is a specific kind of heterosexual relationship in which one can probably identify characteristics such “feminine” or “masculine” love, but even in this case, this specificity will change in parallel to the relationship in society as a whole. To simplify, if we separate sexuality, reproduction and love into different “conceptual clusters”, slowly cutting down heterosexism, all of our notions of love will inevitably change. In my bright future, the choice of partner will be free from all sides; virginity will lose its sacrality (or its obligation), reproduction will become considerably more conscious, sexuality will be more free, and love will define itself through the individual qualities of its participant subjects, rather than through romantic or mythologized factors, regulated by society and culture.

Martha Rosler, New York

Feminists far more theoretically sophisticated and politically engaged than I have addressed the questions you have posed, or variations of them, over the past few decades. My answers can be only a pale echo of what they have to say. The particular strains of feminism that have motivated me have not sought simple economic, and perhaps social, parity with males in society because that leaves open the possibility of simply passing along women’s unequal burdens to those who are of a lower class and economic status –or even to other countries where the wage base is lower. Instead, feminism has consistently demanded a broad reorganization of society so that wealth and privilege are not the determinants of who reaps society’s rewards, on the one side, and who must take up its least desirable or lowest paid tasks, on the other.

Which political role can feminism play in the contemporary world?

Which strategies of solidarity between women of different social, national, and ethnic backgrounds are possible today?

Or is it better to shift our focus from the differences between men and women in order to address different universal features, such as political power-relations or social class?

Feminism insists on the importance of a series of social “becomings” or processes of transformation rather than simply an improved status for women. Feminism, it is true, has already potentiated the recognition of previously “invisible” subjectivities and subject positions, a process that, in turn, has gone beyond the crucial questions of gender to also allow for post-colonial recognitions of the Other. The necessary solidarity of women in the face of patriarchy, thus, is only part of the story, in the face of growing income disparities in every area of the globe and the rapid pace of neo-imperialist “globalization” of labor, including the increase in sexual slavery that sends women and children across borders to the developed North and West from the former East Bloc and the so-called Third World of the global South. Feminists have traditionally included demands that affect poorer women (and children) as part of their agenda, providing a place for those women and children to voice their own concerns and provide testimony and make demands. This is the feminist solidarity that I recognize, not a reductively universalizing one. At the same time, I believe enough in universal human rights to insist that social practices in “traditional” societies (or social sectors) other than my own that damage women, such as genital cutting and mutilation, or purdah, bride burning, child marriage, and other horrors, should not be treated as local customs worthy of silent respect but rather should be investigated as onerous customs that impede women in those societies. Unlike religious missionaries and arrogant “civilizers”, what is required here is a respect for the opinions of indigenous women as well as their suggested solutions, and a long-term commitment to working with them for change.

Do you feel that qualities like “vulnerability” will die out as unnecessary capacities?

Or is it possible to engage in a certain revolutionary politics of vulnerability?

How can feminism convince human beings of both genders of the need for emancipation and of the benefits of real freedom?

My brief and perhaps superficial observation in post-Soviet Russia was that women were, by and large, allowed or forced by the Soviet State into the production process but not allowed to develop political, social and cultural power. Similarly, the productivist state was blind to the elements of “private life” that were in effect women’s domain, including not only social tasks but also the biological processes particular to women. The need to attract sexual partners or mates on the basis of appearance led to a pent-up demand for the cosmetics, clothing, and behavior that were long a part of the women’s masquerade in the West. The withholding of good information about sex and birth control seems to have preserved the prudery and folk beliefs of the general population and led to a yearning for the apparent freeing of the body from the purview of the state–its apparent “depoliticization.” The symbolic value of the naked form as one purged of the demands of citizenship helped fuel the wholesale adoption of pornographic representations of women by the male consumers of that pornography and also provided ideals for women to aim to achieve (especially since Western women’s magazines and cosmetic manufacturers posed essentially the same solutions as the pornographic ones). It was long a truism of the Left that Rockefeller (read: the richest of the rich) is as much a prisoner of class inequality as the poorest person in a capitalist society because of the inability of the individual to express his human powers fully. Women soon pointed out the same about men in a gender-riven society, namely, that the demands of “manhood” require the suppression of many human qualities and behavior–cooperation, empathy, even the ability to grieve, for example–that enhance individual lives and enrich society. In other words, strict gender differentiation with rigid (and hierarchical) models privileges one model and leads to the identification of social power with the role that successfully exhibits the requisite trait suppression. Women need to be the ones to remind society that the commodification of everything damages not only women’s identities and cripples their productive potential but also poisons the well of all forms of creativity. The price paid by all of society is the complete demotion, in favour of popular culture, of the artistic and literary forms that seemed to sustain so much of the human element of Soviet society during the depths of Stalinism and beyond. If young women see nothing that energetically challenges the mindless television and journalistic insistence on women’s hierarchical inferiority and parasitical relation to men, they will not be empowered to seek economic as well as political and cultural equality.

Does love have any political potential in your opinion?

Do you think that there is anything specific in the feminine experience of love?

Big discourses about the transformative potential of “love” can in my opinion cater too much to the mystical New Age tendencies that Russia has historically (and more recently) exhibited (Russia is already too proud of its hypostatized “soul,” too reliant on it to explain national character or individual talents.) Although Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara famously remarked that “At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me point out that the true revolutionary is motivated by love,” it is risky to assume that anyone would understand that this notion is necessarily different from the theological, mystical, or sexual/romantic versions of love. Nevertheless, women and girls – and man and boys – should be encouraged to be value the caring and empathic behavior that contributes to romantic love and to the care and maintenance of children and families, and most importantly, to be unafraid to exhibit it. This does not mean that you have to be a sucker!

Women acting energetically together and making consistent demands for all kinds of social rectification–acting beyond traditional feminine demands and in favor of enlargement of the public sphere–Is necessary. A requisite accompaniment, of course, is the cultivation of lectures, press, and publications that applaud and support this kind of behavior without identifying activist or self-determining women as “masculinized” or unattractive, thus moving the discussion away from Being toward Becoming, away from “condition” toward action. This appears to be a necessary way forward.