There are no translations available.

We are excited by the debate that Dmitry brings to the table. This issue is one of the concerns of our actions, of our artistic/political life. Historically, there have been numerous instances of movements that later, under the yoke of postmodern thought, would be reduced to tendencies. The historical movements and classes have almost become myths. This strategy, woven from academic thought, is meant to frustrate any chance of taking over or rethinking the sense of the collective in art and uniting the same context with each and every juncture. In our particular case, in the nineties, we occupied an old house that belonged to a surrealist artist named Juan Andralis, who had died in Buenos Aires in 1994. In this house we researched materials without the mediation of critics, curators or institutions. It was a direct encounter with objects, photographs, manuscripts, and material that was not even edited.

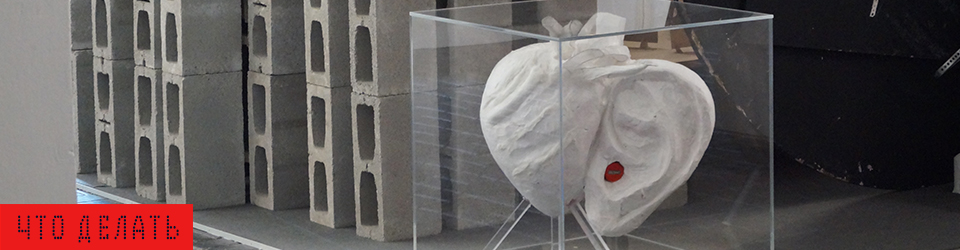

That encounter with Surrealism, in the middle of the nineties, was crucial to the future of our organization. We found that it acted as lubricant for the idea of a movement that proposed changing life. There, within the Surrealist manifesto, was where we made the collective decision to form a group that would try to be part of a movement. Despite the distance between generations, we were profoundly touched by the romantic idea of being part of the engine for change not only in culture and language, but also in society as a whole. But at that moment in Latin America (in our case, Argentina) we were living through a time of economic and political transformation: the neoliberal system had been implemented, with the attendant consequences in the cultural field. The crisis that eventually led to social explosion and the collapse of the economy, in 2001, was just beginning. However, at that time, in the nineties, everyone had been co-opted by the logic of the market and the economization of cultural production. We had to fight on two fronts: against the widespread feeling that nothing could be changed and against the notion that this was the only possible economic model. The idea of globalization was expanding, and it donned a cloak of jokes and ironies when confronted with any proposed politicized cultural movement. The end of history and the death of ideology brought on a widespread skepticism that was cleverly packaged in mega cultural events, large concerts, festivals, and biennials. The idea of cultural consumptionculture as a basic value of the business field, sponsorship was apparently the only possible factor in the field of art and culture. So the field of culture came to occupy the place of the sensible and to produce human subjectivity. It was transformed into the washing machine” of transnational capital. The industry of the cultural washing machine appears before our eyes, when we see the pictures superimposed on drawings of the museum, as a model of the ghost of an old washing machine.

The washing machine is not a new imported model: it is a metaphor for implementing the same rules of the game vis-à-vis a global hegemony that dominates every political-economic and cultural local. It is almost a war of meanings, where we have had to spend years on the barricades in order to lay hold of our symbolic weapons. Now we enter the battlefield in order to recover what belongs to us, the sense of political and spiritual reconciliation that concerns us. It is important to disclose the change in strategy that the washing machine has undergone in recent times. It has begun to wonder whether it should start operating within the exclusion and marginalization of those who question the god of the market as the sole regulator of life and art. Whereas earlier, practices that coupled art and politics in action were denied and vilified, for some years now we have been struck by the turn of the whole industry (music, theater, film, art) toward the independent, the alternative, and the marginal. Now these are value-added processes, and the alternative becomes a site with no official dialectical counterpart. Barriers melt and everything is unified in a single universal model, where questioning the system itself is also part of the showi.e., it also gets a hearing. The new model, launched to capitalize on and prosecute international crises, is the permanent inclusion. This model is powered by its long evolution from the crisis of representation. This important dynamic favors the inclusion of new agents that function as antibodies and thus keep the structure of the system and the cultural industry alive. Just as the debate shifted from a supposed crisis to a supposed normality and the expectation of change, the role of social movements, activists, artists, theoreticians, and institutions also moved towards another type of scenario. Were not talking about the start of the crisis, but about acceptance of it as a present continuous and its consequences as something normal.

The crisis as a temporary state of emergency leads to a permanent situation: life amidst injustice and insecurity. The notion of inclusion is the keystone to the cultural policies that current governments in different parts of the globe are adopting. The inclusion is a symbolic illusion: it is the idea of the return of being part of something. This strategy, however, does not eliminate class conflict and conceals the internal tensions within the field. What Is to Be Done? So, from our perspective, at this moment it is indispensable to rethink our work. While we have been and are part of networks, groups or crowds, although we have contributed to the overall social and cultural resistance in the streets in demonstrations, protests, meetings or publications, we have always acted in response to a certain social process (e.g., at a summit meeting of presidents or at a global forum). The movement of movements is here and there and moves on. It is reticulated: it self-organizes and grows. But it is time to start focusing our action not only on the problematic of other agencies and sectors, but to give battle in the cultural system itself. The spaces of art and culture are areas where power is produced: overall communication strategies, pre-set design models, and social stereotypes. Politicians have made performance a part of their public events and use art in their election campaigns or to stay in power. Art is food for the machine of the culture industry since distribution is terribly elitist.

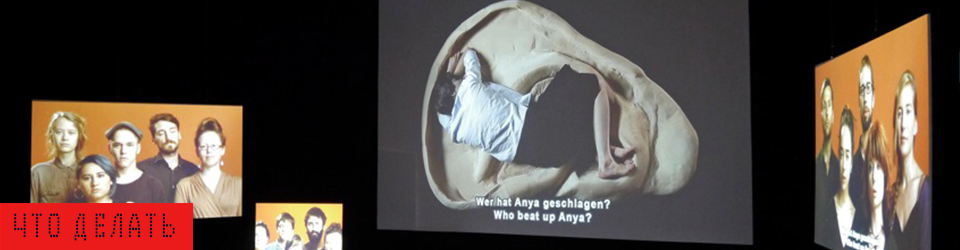

If we continue letting our open field slip into the maw of the publicity-hungry monster, our future will be very dark. Perhaps it is time for re-generated groupings to expand networks that link organizations and subjects to collective construction, that seek to dissolve the distance between inside/outside, national/international, and center/periphery. Perhaps it is time to return to the spirit of criticizing the action as a constant within the cracks of the system. For the art system is more comfortable with the mediations of curators, art historians and critics; it is they who set the terms of the discussion. Therefore, we need to retrieve the voices of the creators, of both sides in the practice of art and social practice. We were interested and we are interested in retrieving this space of prominence in conjunction with social organizations and other social actors. This doesnt mean representing them, but presenting all of us together. But now we are entering a new historic moment where once again the relationship of art and society will turn. It seems that each time this turn takes the elements of cultural representation that are presented by the lived socioeconomic model. The brand functions aesthetically as a good guide to the paths of subjective social life at all times and places. Clashes of trends and movements, however contradictory, are indispensable to the survival of a renewal in the arts and thought. They are the raw material of all intellectual production.

Any collective experience tests a series of human values: solidarity and commitment intersect with the context, with institutions, with the art system, and with a series of links that are generally bound up with competition. It is now critical to highlight solidarity and oppose the idea of competitiveness among peers. Ethical values will again be outsourced in the artistic field, but those allegiances need to be formalized, to be based on means appropriate for this new time without losing the attributes of total freedom and creative independence. The search for new systems of representation and the formation of movements are challenges for any society that needs to remake its values. Participation in this process is an essential gesture for the times through which we are living. An experience of social and spiritual renewal, in which the bonds of the social will be reclaimed, awaits us in the midst of the contemporary lifes endless contradictions.

We will take part in the construction of this movement through trial and error. We will revive the isms with the International Erroriat, taking these mistakes as something positive for our future as a society. We will install them subtly criticized in everyday language, turning terms into actions and actions into situations. By expanding these errors, we will make a contribution and make the movement we are building together more dynamic. We will try to put the system into crisis because we know that the interruption of a hegemonic discourse opens spaces and launches new ages. From this collective experience we can say: One is what one doesnot what one says, not what one thinks.

Loreto Garin Guzman / Federico Zukerfeld The text includes some sentences and ideas from the text “La Papa Caliente” (“the hot potatoes” ) written by Eduardo Molinari, Loreto Garin Guzman , Federico Zukerfeld as a curatorial text for the Catalogue of LaNormalidad (3 part of ExArgentina Project) in 2006.