#10-34: В защиту репрезентации

Дмитрий Виленский // В защиту репрезентации

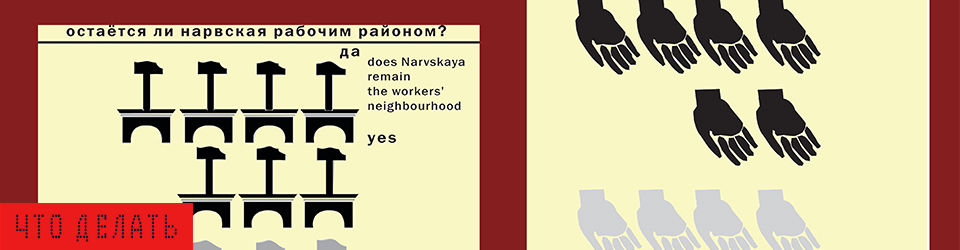

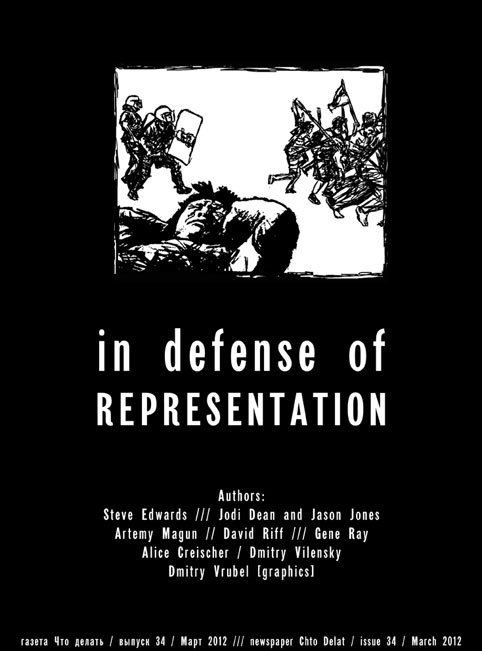

Этот номер газеты «Что делать?» является реакцией на текущую дискуссию о необходимости и возможностях политической и эстетической репрезентации. Проблематика этой темы, сформулированной еще Платоном, по-прежнему остается в центре споров об искусстве и политике сегодня. В складывающейся ситуации доминирования «анти-репрезентационных» стратегий – как в среде новых политических движений, так и в сфере политически ангажированного искусства – кажется, вся дискуссия редуцирована к простой и понятной схеме: РЕПРЕЗЕНТАЦИЯ = ИЕРАРХИЯ = ПЛОХО; ее антитезис, соответственно: НЕТ РЕПРЕЗЕНТАЦИИ = НЕТ ИЕРАРХИИ = ХОРОШО

В этом номере мы стремимся показать, что эта проблематика требует более детального анализа.

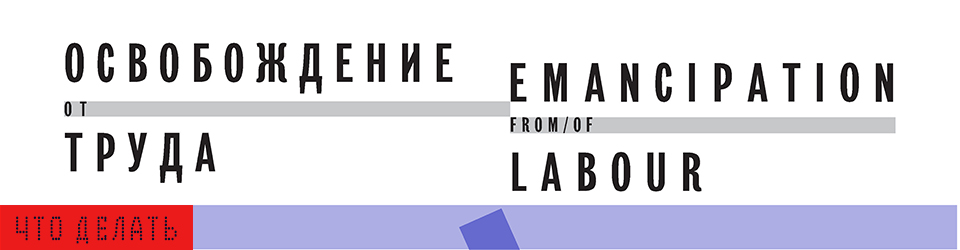

И стоит это сделать не ради академического пересмотра употребления определенных терминов, а для решения острейших вопросов продолжения практик освобождения в мире, находящемся в ситуации серьезного и затяжного кризиса становления политического сознания. Мы полагаем, что имеет смысл исходить из старой и становящейся все менее понятной максимы, а именно: обретение сознания и есть предпосылка любого развития и освобождения, и любой акт осознания положения вещей, общей картины мира есть акт репрезентирующий.

Gene Ray // Radical Learning and Dialectical Realism: Brecht and Adorno on Representing Capitalism

There are no translations available.

First published at Historical Materialism 18.3 (2010)

This set of problems has a history, and Brecht is a key figure in it. If I like others am drawn to Brecht at this moment, it presumably is because the problems themselves point us back to his works and positions. Rereading Brecht, I have kept Adorno open on the table. I have tried to maintain the pressure that each puts on the other, and to think from that tension about the challenges of representing capitalism in art. Brecht’s works were aimed at producing pedagogical effects, at stimulating processes of radical learning. He took art’s relative autonomy for granted but refused to fetishize that autonomy or let it become reified into an impassable separation from life. He based his practice on the possibility of re-functioning and radicalizing institutions and reception situations. Adorno, in contrast, made the categorical separation from life the basis of art’s political truth content. In its structural position in society, art is contradictory: artworks are relatively autonomous but at the same time are “social facts” bearing the marks of the dominant social outside. Paradoxically, only by insisting on their formal non-identity from this outside can artworks “stand firm” against the misery of the given. Adorno’s position is first of all a categorical or structural one; it generally is not oriented toward effects or specific contexts of reception. Except, as will be shown, when it comes to the works of Beckett and a few others. The radically sublime effects that these works ostensibly produce led Adorno to advance them as counter-models to Brecht.

David Riff // “A representation which is divorced from the consciousness of those whom it represents is no representation. What I do not know, I do not worry about.”

There are no translations available.

There is something uncanny in this quote from Marx, torn out of context and pasted into a fresh document 150 years after it was written. [1] It’s like looking into a mirror where there should be a window. It describes the status quo of our own spectacular world: a massive accumulation of non-representations, all divorced from consciousness. But at the same time, this is a world where self-representation, implying self-consciousness, claims to be everywhere, on mobile devices, in cars, airplanes, and even on remote desert islands. Representative machines previously only available in big clunky institutions are now open for everyone’s use. Consciousness is everywhere as a potentiality. But the pressure is too great. You have to represent. You have to hand in this text. Don’t think. Write. Self-expression before self-knowledge; find the right quick phrase for a certain state of subjectivity, shot out ultra-rapid in a network of friends, where it quickly loses connection to the consciousness that supposedly created it, becoming a micro-commodity, or a firing neuron in some collective mind we do not yet fully understand. Stop complaining. Represent.

Artemy Magun // The post-communist revolution in Russia and the genesis of representative democracy

There are no translations available.

“Representative democracy” is, at the moment of its emergence, an oxymoron. Representation, and in any case the electoral representation, has always been considered an aristocratic institution. Rousseau saw it as a “modern”, that is medieval, feudal, form of government, linked to the institution of estates. Representation referred to the estates (even in Locke), or – in Hobbes or Bossuet – to the incorporation of both God and society in the figure of the monarch. The model of Sieyès, where the representatives of the estates were to become constituent power, representing the sovereign nation, merged the two (contradictory) senses of representation together. The oxymoronic formula sends from its both terms away to something else – namely, to the contradiction itself which, far from being since then “sublated”, is perpetuated and may at any time turn its restorative-conservative or radical utopian side. Furthermore, this formulaic tension is in fact a sign of the event which goes beyond the concept but which opens up its internal contradiction and determines the tendency that would prevail for a time.

Jodi Dean and Jason Jones // Occupy Wall Street and the Politics of Representation

There are no translations available.

Debates over demands, tactics, and the ninety-nine percent have featured prominently in Occupy Wall Street since the movement’s inception. Movement participants argue over whether Occupy should make demands or whether occupation is its own demand. Activists debate whether the movement should pursue a diversity of tactics or explicitly disavow violence. People with varying degrees of involvement in and acceptance of the most significant political development on the left since the anti-globalization protests ask themselves if they are part of the 99% and what it means if they are. Underpinning these debates is the question of representation. What does the movement represent and to whom?

To present the disagreements simultaneously constituting and rupturing Occupy as fundamentally concerned with representation is already to politicize them, to direct them in one way rather than another, for the question of representation has been distorted to the point of becoming virtually impossible to ask. Strong tendencies in the movement reject a politics of representation. Rather than recognizing representation as an unavoidable feature of language, process for forming and aggregating preferences (always open to contestation and revision), or means of producing and expressing a common will, these tendencies construe representation as unavoidably hierarchical, distancing, and repressive (and they think of hierarchy, distance, and repression as negative rather than potentially generative attributes). For them, the strength of Occupy is in its break with representation and its creation of a new politics.

Steve Edwards // Two critiques of representation (against lamination)

There are no translations available.

A little story has developed in the circles of the political and artistic avant-garde. It is more often spoken and heard than written and read, but it constitutes the background common sense for much thinking about politics today. This assumption suggests that the critique of representation and the critique of parliamentary representation (bourgeois democracy) are equivalent and coeval. In politics (the Occupy movement, for example) this entails the rejection of any representative or spokesperson, in favour of horizontal decision-making, whereas the rejection of bourgeois formal democracy for some contemporary artists and critics suggests the necessity of an exodus from the bourgeois art world of museums, galleries and all their trimmings. Involvement in this system is imagined to be undemocratic, since it entails working in hierarchical institutions, dependence on capital (whether state or private in form) and assuming to represent, or speak for, others. Autonomy in politics is equated with autonomy in art. Followed through, the alternative would be something like direct democracy in art: soviets of artists, workers and soldiers deputies, which would certainly not be a bad thing. However, the story rests on an imaginative process that laminates distinct critiques (practices and ideas). In order to think about this composite we need to begin by examining the constituent layers.